In June, we will be concluding our Tuesday Matinees series looking at the state of American cinema 50 years ago, specifically the years from 1969 to 1972. The coming month’s focus will highlight a genre that reached a new peak and embedded itself further into our cultural fabric: the crime film. The influence of these films is still felt today and considered to be a high-watermark for not only the genre, but for American film as well.

Emerging between the receding wave of the counterculture and the build-up to the Watergate scandal, the crime genre took a turn for the gritty during this time. Not since the rise of Depression-era gangster pictures had there been such a level of humanizing and lionizing criminal life on-screen. The difference between the two eras is that the studios were no longer bound by the Hays Code to mask the genre’s thrills as morality plays about the dangers of living outside of the law. When Jack Valenti assumed the presidency of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) in 1966, a new rating system replaced the outdated Code and thereby opened the doors to more realistic and bleak depictions of criminal activities on-screen. Similarly, more and more of these films began to express the ethical quandaries of living in the increasingly broken world of the late 60s and early 70s. You either lived and died by your own rules outside of corrupt authority, or you had to break the law in order to keep some semblance of it.

This in part led to a new horizon in American cinema; one that led to less creative restrictions and gave rise to the New Hollywood generation of filmmakers as well as the explosive dawn of the blaxploitation subgenre. More so than any other genre of the era, the crime films of the time marked a turning point and a new hope for the industry at large.

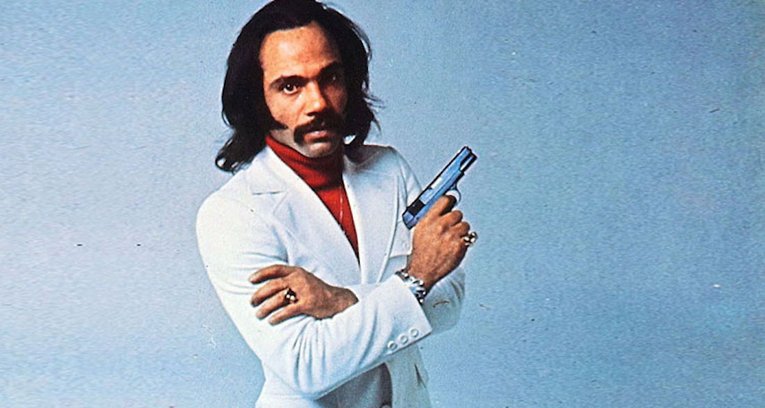

June 4 | Super Fly

1972, 93 minutes, 35mm | Directed by Gordon Parks, Jr.; produced by Sig Shore; written by Phillip Fenty; with Ron O'Neal, Carl Lee, Julius W. Harris, Sheila Frazier, and Charles McGregor

Priest (Ron O'Neal), a suave top-rung New York City drug dealer, decides that he wants to get out of his dangerous trade. Working with his reluctant friend, Eddie (Carl Lee), Priest devises a scheme that will allow him to make a big deal and then retire. When a desperate street dealer informs the police of Priest's activities, Priest is forced into an uncomfortable arrangement with corrupt narcotics officers. Setting his plan in motion, he aims to both leave the business and stick it to the man.

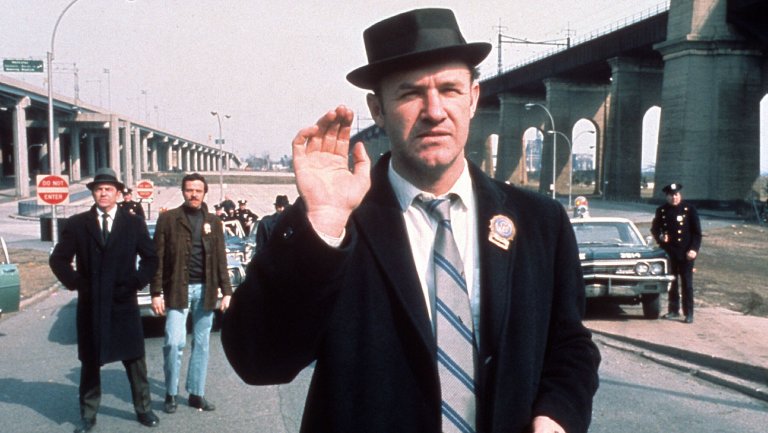

June 11 | The French Connection

1971, 104 minutes, 35mm | Directed by William Friedkin; produced by Philip D'Antoni; written by Ernest Tidyman; with Gene Hackman, Fernando Rey, Roy Scheider, Tony Lo Bianco, and Marcel Bozzuffi

William Friedkin's gritty police drama portrays two tough New York City cops trying to intercept a huge heroin shipment coming from France. An interesting contrast is established between "Popeye" Doyle, a short-tempered alcoholic bigot and a hard-working and dedicated police officer, and his nemesis Alain Charnier, a suave and urbane gentleman who is nevertheless a criminal and one of the largest drug suppliers of pure heroin to North America.

June 18 | The Godfather

1972, 177 minutes, 35mm | Directed by Francis Ford Coppola; produced by Albert S. Ruddy; written by Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola; with Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, James Caan, Richard Castellano, Robert Duvall, Sterling Hayden, John Marley, Richard Conte, and Diane Keaton

Widely regarded as one of the greatest films of all time, this mob drama, based on Mario Puzo's novel of the same name, focuses on the powerful Italian-American crime family of Don Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando). When The Don's youngest son, Michael (Al Pacino), reluctantly joins the Mafia, he becomes involved in the inevitable cycle of violence and betrayal. Although Michael tries to maintain a normal relationship with his wife, Kay (Diane Keaton), he is drawn deeper into the family business.

Join us each Tuesday at 1 pm in the Bing Theater for these classic screenings.