The Jeweled Isle: Art from Sri Lanka, on view through this Sunday, July 7, was motivated by several considerations, especially the size and strength of LACMA’s own permanent collection of artworks from the island. Our collection spans nearly two millennia, from the 2nd century well into the 19th, and encompasses a range of objects in various media, 90 of which are on view in the exhibition. Our greatest challenge was in organizing these works in a manner that conveyed both the beauty and originality of Sri Lankan art and culture, as well as the island’s complex history. As it turned out, several 19th-century photographs of Sri Lanka, recently acquired by LACMA’s photography department, proved to be something of an inspiration.

They included lush images of the island that resonated with the exhibition’s title in various ways. “The Jeweled Isle” in our title comes in part from references, dating back as early as the 4th century BCE, to the mining of precious gems in Sri Lanka. It also recalls much later visual descriptions by European travelers who employed gem-laden phrases—“emerald canopies” and “sapphire skies”—to describe the island’s beauty. As we began to research the photographic archive for Ceylon (as Sri Lanka was called until 1972), we were thrilled, and somewhat surprised, to find several rich collections in the Los Angeles area. In viewing these collections, we came to realize that photography could serve the exhibition in a number of interesting ways.

![Left: Charles T. Scowen & Co., Gateway on the West Side of the Sacred Bo Tree Enclosure, Sri Lanka, Anuradhapura, c. 1880–90, Collection of Catherine Glynn Benkaim and Barbara Timmer, photo courtesy of the lender; Right: Charles T. Scowen & Co., Ambastalawa [Ambasthala] Dagoba, Mihintale, Sri Lanka, Mihintale, c. 1880, Collection of Catherine Glynn Benkaim and Barbara Timmer, photo courtesy of the lender Left: Charles T. Scowen & Co., Gateway on the West Side of the Sacred Bo Tree Enclosure, Sri Lanka, Anuradhapura, c. 1880–90, Collection of Catherine Glynn Benkaim and Barbara Timmer, photo courtesy of the lender; Right: Charles T. Scowen & Co., Ambastalawa [Ambasthala] Dagoba, Mihintale, Sri Lanka, Mihintale, c. 1880, Collection of Catherine Glynn Benkaim and Barbara Timmer, photo courtesy of the lender](/sites/default/files/attachments/Photo%202_Bo%20Tree%20Enclosure-3.jpg)

Because there is so little Sri Lankan stone sculpture or narrative painting beyond the confines of the island, we turned to photographs to provide some historical context for the objects in the exhibition. The establishment of Buddhism, in particular, and the construction of Sri Lanka’s earliest monuments, were closely linked to the arrival of relics. These included bodily traces of the Buddha and other venerated teachers—a hair or bone, for instance—as well as relics of use such as the Bodhi tree where the Buddha gained enlightenment. A sapling from the Bodhi tree at Bodhgaya was planted at Anuradhapura in the 3rd century BCE, conceptually linking the island with the Buddhist heartland in India. The relics of the Indian monk Mahinda, who brought the dharma to Sri Lanka, were enshrined at Mihintale, site of the island’s first monastery. The Buddha, his relics and teachings, and the monastic community he founded, strike additional notes of resonance with the exhibition’s title, for all are considered “gems” in Buddhist texts.

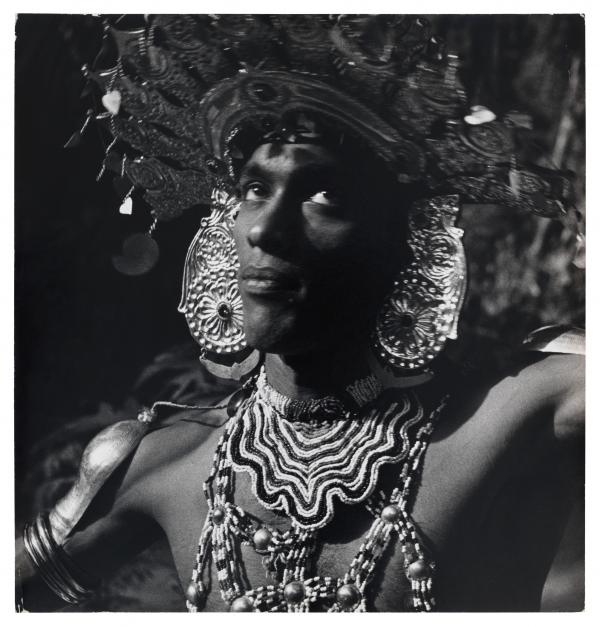

The most important relic in Sri Lanka today is the Buddha’s tooth, which arrived from India in the 4th century and quickly became a palladium of kingship. It is still housed in a temple at Kandy, and is the focus of an annual procession that takes place in the late summer. Several late 19th-century photographs in the exhibition give visitors some sense of the temple’s setting and the rich pageantry of the relic’s public display each year.

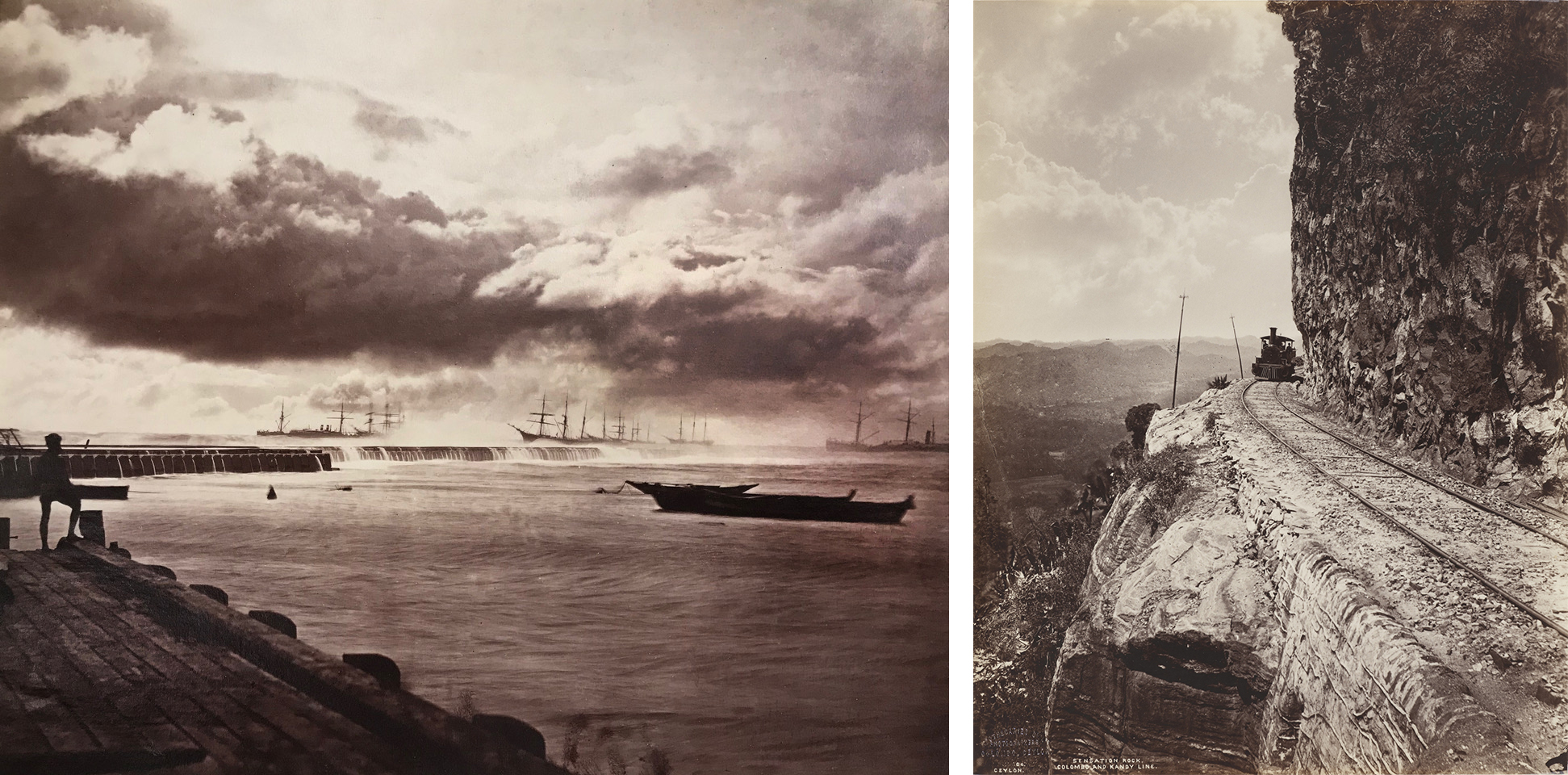

Like the few images shown above, 71 of the prints in the exhibition were taken by British commercial photographers. In the late 19th century, these men were among the most assiduous observers of Ceylon, documenting its landscapes, monuments, people, festivals, and customs. In placing their works in every section of the exhibition, we intended the photographs to serve multiple and overlapping functions. The prints are exceptional aesthetic objects. They offer context, but always return the gaze to the beauty of the island and its traditions. Collectively, they also serve as an important reminder of Sri Lanka’s late colonial history. The Portuguese, Dutch, and British successively occupied Sri Lanka for nearly 400 years, but British colonial forms of knowledge —including visual ones—would have the greatest impact on the modern history of the island nation.

Charles Thomas Scowen (c. 1852–1948), whose studio was one of the leading commercial establishments in Sri Lanka, was responsible for some of the most accomplished botanical photographs of the colonial period, several of which are displayed together in the fourth gallery of the exhibition. Most of these photographs are set in the Peradeniya gardens, which were the royal gardens of the Kandyan kings. After deposing the last king of Kandy in 1815, British colonial authorities appropriated the gardens. Peradeniya became another link in the British imperial network of botanical centers facilitating the vast global exchange of plants and scientific knowledge. Behind the beauty of these photographs, then, lies a complex, often dark, history.

Among the botanical portraits are two photographs depicting varieties of the coffee plant. Although we tend to associate Sri Lanka with tea, coffee was the island’s first major export crop. The Dutch had tried to cultivate it, with no success, in the coastal regions. The British, who managed to infiltrate the island’s interior, found that it grew very well in the central highlands. Thus began their massive interventions in the Sri Lankan landscape, as revealed by additional photographs on an adjacent wall.

The British cleared vast forests and introduced a plantation economy in the highlands. To facilitate the transport of the crops, they excavated rail lines and expanded coastal ports. The rise of Colombo harbor was largely due to the construction of a huge breakwater there between 1875 and 1885. This followed the completion of the Colombo-Kandy railway line, in 1867, which connected the hitherto remote interior of the island directly with the coast. Coffee was Sri Lanka’s major export crop until about 1900, when a fungus ravaged the coffee plantations and tea was cultivated instead.

Almost all the botanical images, and the above photograph of Colombo Harbor, were chance discoveries arising from a random visit to a photography gallery in Bergamot Station. These moments are amazing for curators, as we encounter objects that we aren’t necessarily seeking but that end up redefining our exhibition perspectives and narratives.

It was another stroke of luck that led us to the photographs of Reg van Cuylenburg (1926–1988), which figure prominently in the last gallery of the exhibition and provide an important counterpoint to the colonial views. We were familiar with van Cuylenburg’s work only through a 1962 publication—Image of an Island: A Portrait of Ceylon—which featured a gorgeous image of a Kandyan dancer on its cover.

One of our exhibition designers, Ravi Gunewardena, came across a posthumously published memoir and, through the publisher, tracked down van Cuylenburg’s widow, Margaret Kay Dodd. She generously allowed us to borrow whatever we wanted for the exhibition and, a few weeks before its opening, gifted the prints to LACMA. Reg’s photographs are a wonderful summation of the exhibition, for he was a native-born Sri Lankan, of Kandyan Sinhalese, Dutch Burgher, and English descent. At a young age, he was introduced to Lionel Wendt, Sri Lanka’s most famous modernist—also of mixed Sinhalese and Burgher parentage—from whom he learned art and photography. Sri Lanka gained its independence in 1948, and in the decade that followed, van Cuylenburg undertook several tours across Sri Lanka, extensively documenting a wide variety of places, festivals, and people. His photographs present a certain post-colonial optimism, a reveling in the re-discovery of home and country. We hope our exhibition allows visitors to similarly enjoy an exploration of Sri Lanka’s rich history and artistic traditions.

Visit The Jeweled Isle: Art from Sri Lanka in LACMA’s Resnick Pavilion through its closing date, this Sunday, July 7, 2019.