About four years ago, when I was informed by our department head, Stephen Little, that the first Korean show to be carried out as part of The Hyundai Project: Korean Art Scholarship Initiative at LACMA, would be on Korean calligraphy, several thoughts immediately came to mind:

- This could not be like a typical calligraphy show in South Korea familiar to many people who have spent time there—shows in a small space, generally in towns or alleyways where older men of the community casually hang their latest creations of ink on paper while they smoke, drink, and congratulate each other, often oblivious to the few people who stop by.

- Where and how would we find enough research materials to produce helpful information in English for the exhibition catalogue?

- How do we make Korean writing—illegible in both hanja and hangeul for most potential visitors—appealing and engaging?

In other words, the foremost question that guided the following four years was, how do we present Korean calligraphy to be relevant today?

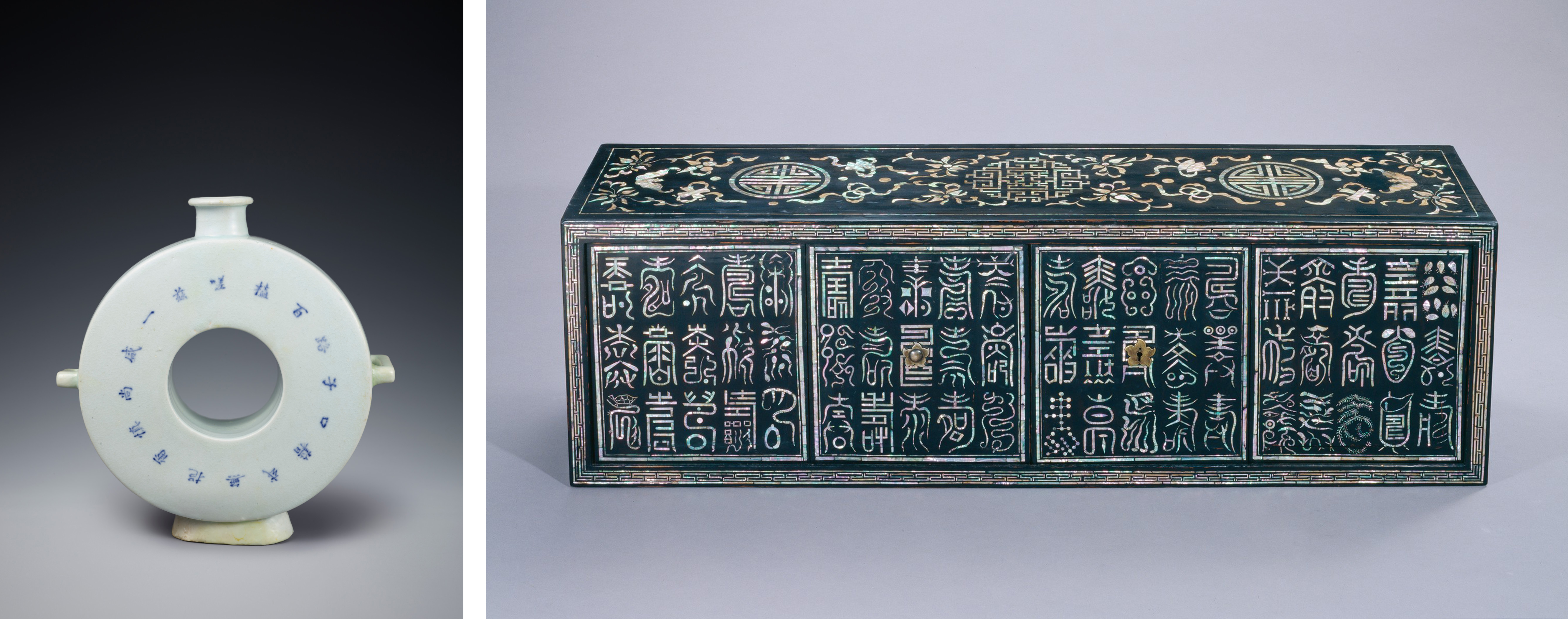

There has been quite a bit of buzz that this kind of show had never been organized outside Korea. Frankly, I would argue that conceptually it has not been done in Korea either and this has been confirmed by museum directors in Korea. While this challenge could be seen as daunting, actually it was liberating to broaden the notions of calligraphy from a specific art form to writing to include ceramics, lacquer, branding irons, metal types, newspapers, and ink rubbings. It was equally liberating to expand the timeline to bring forth the experiments of contemporary artists who each challenged the traditional assumptions of line and writing to postmodernist concerns of spirituality, a jump to the field of graphic design, exaggerations of pictoriality, abstract art, and a photograph of performance art.

While Los Angeles is home to the second largest population of Koreans outside of Korea, Beyond Line is not just for Koreans; it is for everyone who has an interest. In this regard, a great effort was made toward the exhibition catalogue. Many of the works and poems were translated from hanja or hangeul to English by members of our department and other staff at LACMA who are bilingual in Korean and English. Much of the research information for the catalogue entries is thanks to the bilingual interns from Korea who had access to restricted Korean databases requiring a Korean citizenship number, akin to a social security number.

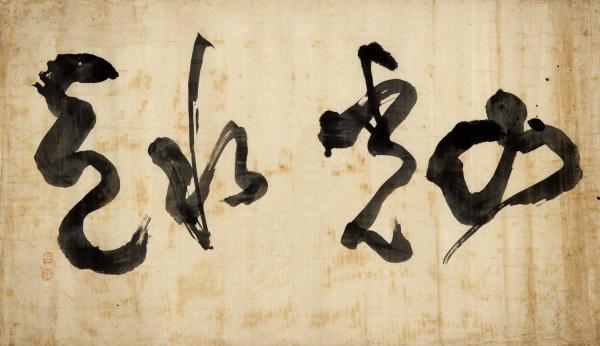

Still, the largest challenge was working with our Korean colleagues across the ocean. Despite cultural advancements in South Korea, there were, and still are, deep differences and assumptions about how U.S. museums and art institutions work. There were numerous hurdles and some disappointments. The biggest one was notably the National Palace Museum, a museum that is part of the Korean government system, who cancelled our request for loans approximately two weeks before the show was to install. We were left with an entire wall empty in the Royal Calligraphy section. But, with every seeming disaster, there is a silver lining. In this case, calligrapher Jung Do-Jun, whose work was already in the exhibition as part of our contemporary section, Beyond the Modern, stepped forward and researched a historic work comprising eight hanging scrolls to recreate from scratch that would perfectly fit the abandoned wall. It was a work that King Seonjo (r. 1567–1608) had originally composed in cursive script showing two poems by Chinese poets. Jung was so concerned with accuracy that he managed to use the same ink (likely a recipe) and same colored hanging scrolls as the king’s work himself. This magnificent “save” was practiced, painted, and crafted into hanging scrolls in three weeks—in time to be hung in the gallery for the opening.

Jung also “performed” the same work for the opening night audience and a few days later, he painted with a very large brush outdoors on the Smidt Welcome Plaza. The challenge of painting calligraphy with such a large brush is first the physical challenge it puts on the human body, but also the challenge of “seeing” ahead to be sure that the character, far bigger than yourself, is painted accurately, beautifully, and with intention. Counting these eight hanging scrolls that Jung has generously chosen to contribute to LACMA, the exhibition includes roughly 90 works of which approximately 95% were borrowed from Korean museums, institutions, and private individuals, including some of the artists.

While the Bangudae Petroglyphs represent writing’s Neolithic beginnings, the tomb bricks nestled in the Orientation section serve as the earliest examples of hanja (Chinese characters) in the show. Due to their early dating, the tomb bricks not only show the stamped production of hanja on clay bricks, but physically affirm the political and cultural relationship between Korea and China.

The small, but delicately beautiful cursive script of Sim Saimdang (1504–51), the only non-royal female privileged and designated with fame for her Confucian virtues during the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) was honorably placed in a prime location in the Yangban (Scholar-Officials’) Calligraphy section. It is a historical paradox to have a woman be so singularly celebrated in a predominately male Confucian society and she is someone I would choose to have coffee with if I could.

Korean newspapers, like The Independent (Korea’s first newspaper), are displayed in the Early Modern section. Significant for demonstrating the evolution and use of hanja and hangeul metal type, these are an invention from the Joseon period, dating before the printing of the Gutenberg Bible, long considered a benchmark for metal type. The metal types were modernized in late 19th century Korea to allow the newspapers to be printed in 100% hangeul, 50% hanja/hangeul, and English. This selection of newspapers consciously coincided with a politically challenging birth of a modern era, but in the process of communicating the approaching takeover by Japan of Korea, solidified the embrace of hangeul as the nation’s main language—450 years after its invention in 1443. The official guide to hangeul, the Hunminjeongeum—an exact copy of which is featured in the exhibition—was released by the royal palace in 1446.

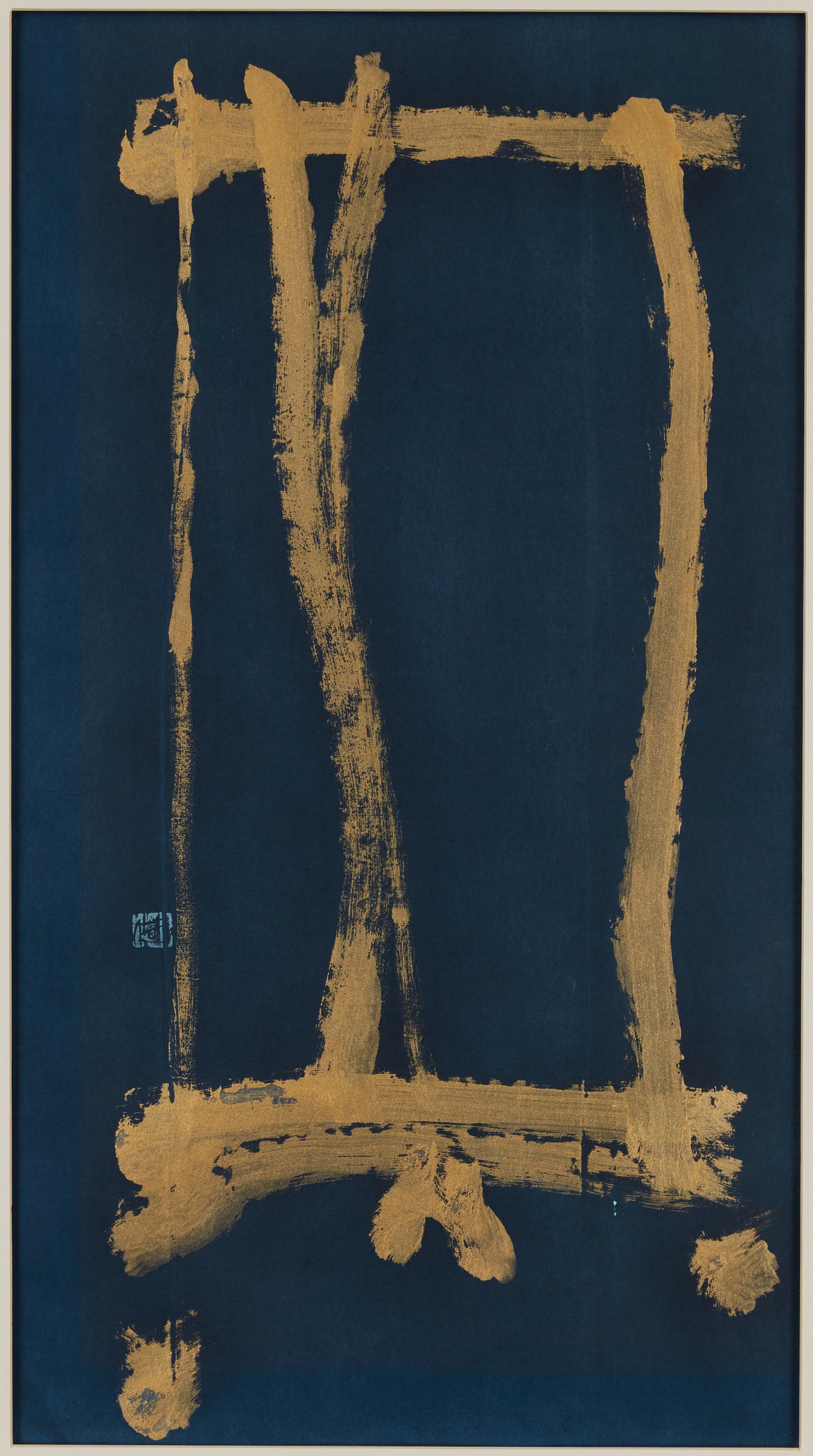

The work by Sun Wuk Kim (1929–2012) in the Beyond Modern section, shows the fight and concern for calligraphy and writing’s future. Kim was a local Angeleno who lived his life dedicated to sharing Korean calligraphy with other calligraphers all over the world, to both learn and take the field further and to present the idea of a new kind of calligraphy; all while being a neurosurgeon during the day. Notably, his work Emptiness plays with color, instead of the traditional black ink and white paper. He chose to paint an abstracted version of the character, “emptiness” in gold, both to harken back to the beauty of Buddhist illuminated manuscripts of Goryeo (918–1392) and to artistically suggest that calligraphy is not about the traditional color, but about the modern notion of abstraction and creativity. This is the spirit of all the contemporary artists in the show.

Finally, the humble works on paper done by, and for, the slave class (nobi) were done at the end of the 19th century, but in many ways, they represent the future of Korean scholarship. The documents are still largely unknown in Korea and confirm for visitors of our show that at that time, hangeul finally reached the lowest classes in Korea. More significantly, these are only two of 6,000 documents housed at the Academy of Korean Studies (Jangseogak) waiting to be researched to finally complete and illuminate an aspect of Korean history that had been unknown—the stories of the individual slaves.

The title Beyond Line: The Art of Korean Writing tries to make the point that all these works were done by individuals, thus revealing the humanity of the Korean people, instead of being reduced to simple lines. To me, this is how we should present Korean calligraphy and writing today.

Beyond Line: The Art of Korean Writing is on view in the Resnick Pavilion through September 29, 2019.