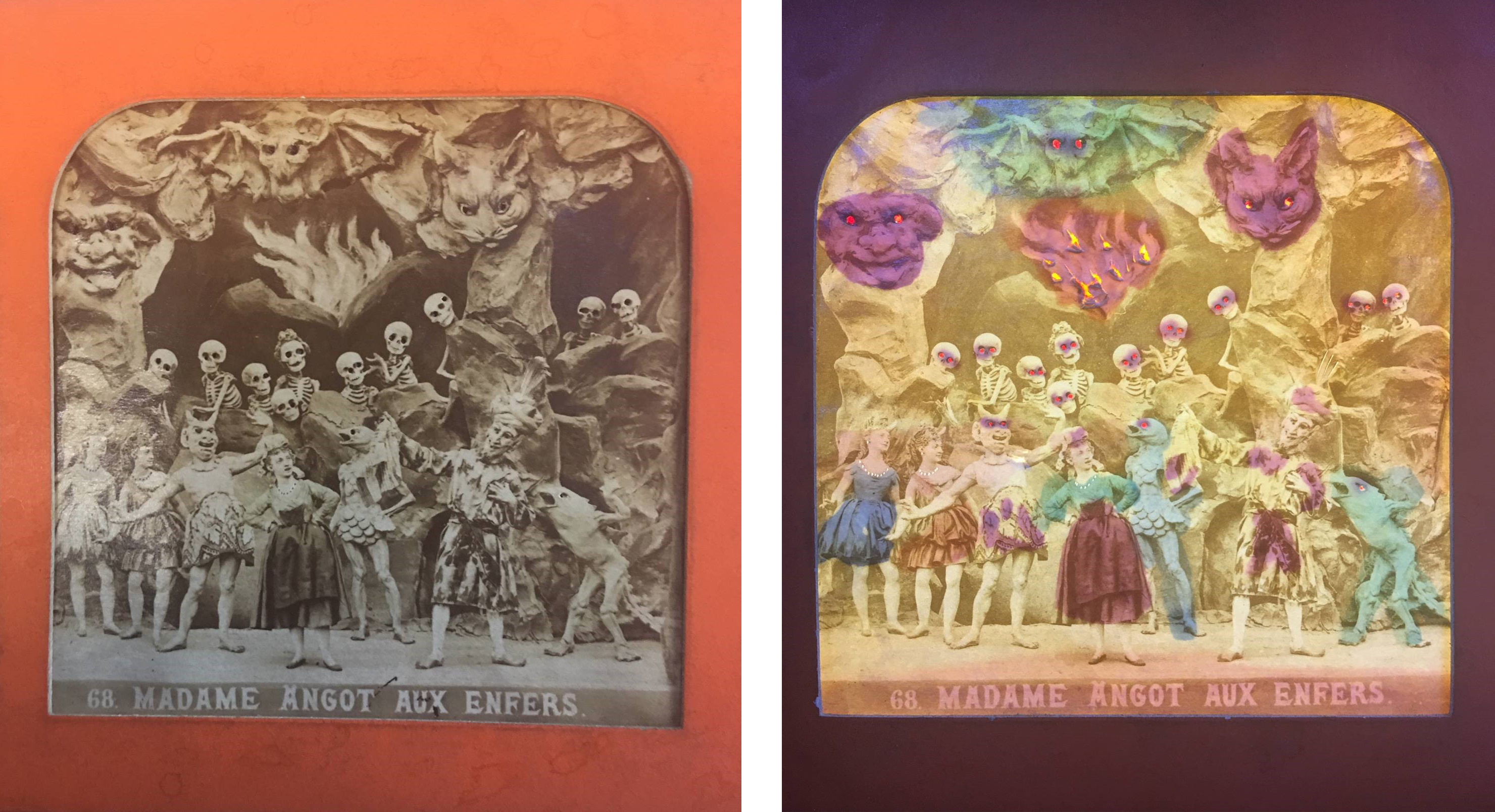

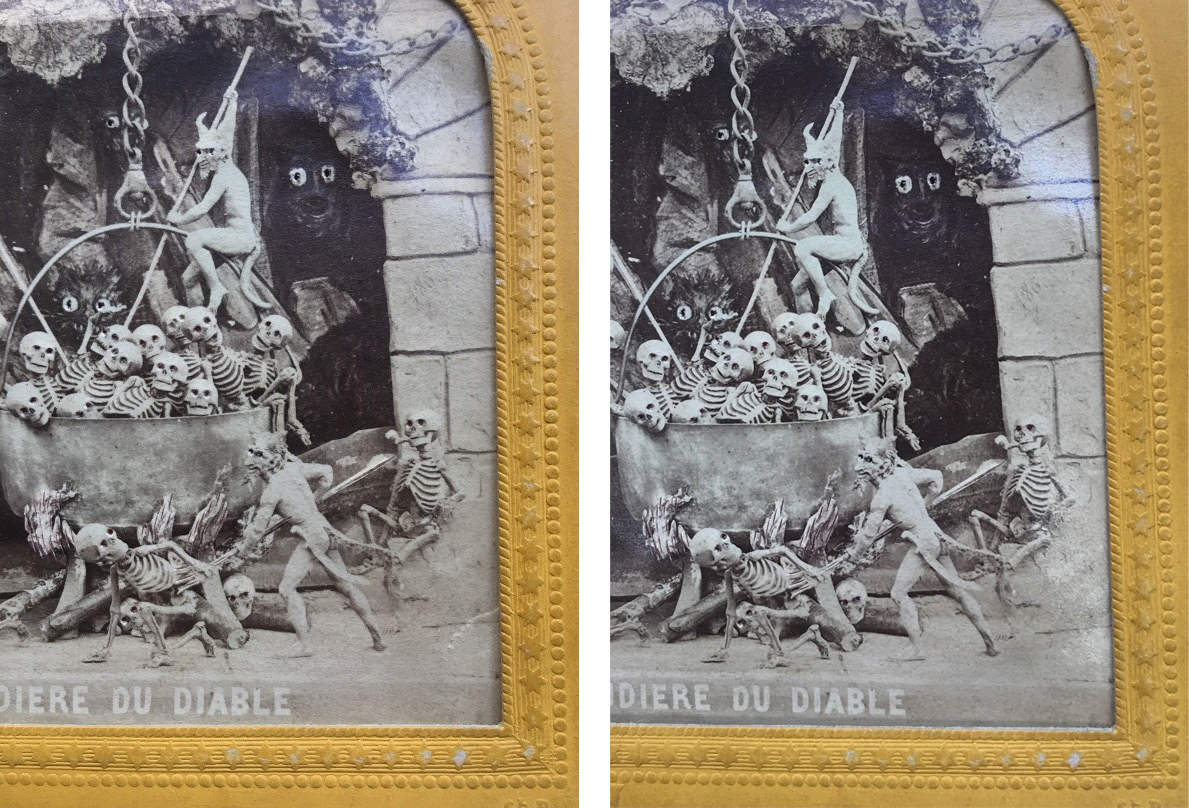

You may have seen several Diableries on view at LACMA if you visited our past exhibition, 3D: Double Vision (on view July 15, 2018–April 1, 2019). These delightful stereographs were made in France in the late 19th century. Albumen prints capture scenes modeled in clay of Satan participating in various activities—everything from playing card games in his parlor to boiling skeletons in a cauldron. The stereographs are particularly charming because they were intended to be observed in both normal light, and backlit. In normal light, the albumen photographs read as a day scene in black and white. When backlit, they become a night scene, suddenly appearing in vivid color. This effect is possible because each photograph is hand-colored on the reverse, and in transmitted light, the colors become visible through the paper.

STRUCTURE:

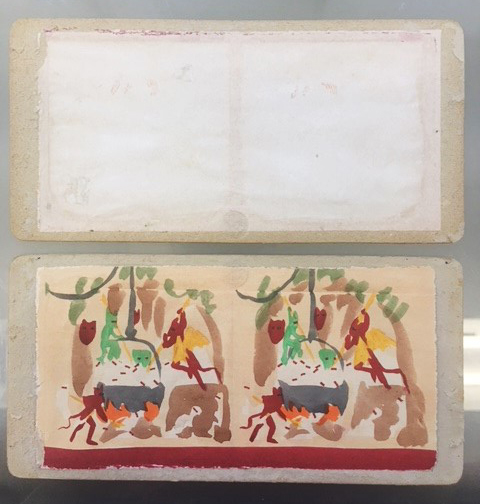

The Diableries are a type of stereograph known as a “French tissue.” They are composite structures, generally comprising four layers. From top to bottom the layers are: 1) front card with two cutout windows; 2) albumen photograph on thin paper; 3) tissue paper; and 4) back card with two cutout windows. The tissue layer acts to diffuse light and to obscure any hand coloring on the back of the photograph layer, increasing the element of surprise when the object is backlit.

TREATMENT:

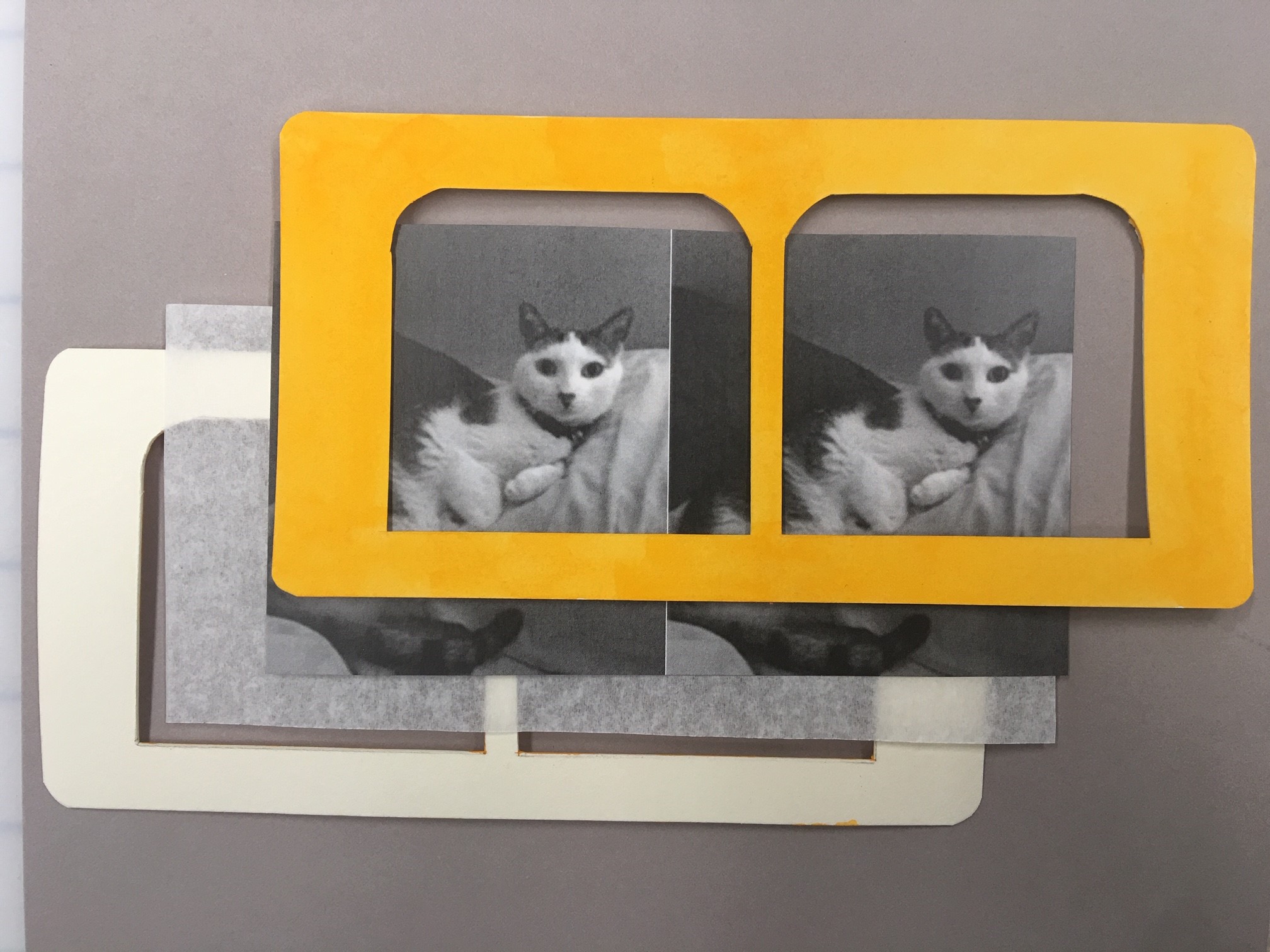

LACMA recently acquired 20 Diableries stereographs. Before they could be exhibited, however, many of the stereographs required treatment to address tears in the photograph or tissue layers. These tears allowed light to shine through unfiltered when backlit, distracting from the darker, surrounding image.

In order to mend these tears, I needed access to the inside of the affected stereographs. Working very carefully, I was able to partially or fully open the works, separating them into two layers: 1) the front window card adhered to the albumen print; and 2) the back window card adhered to the tissue.

I mended the tears from the inside using narrow strips of paper made from microfibrillated cellulose. This paper is extremely thin and translucent. Once adhered in place, it was invisible in transmitted light, making the mends as discreet as possible.

While the stereographs were disassembled for treatment, there was an opportunity to examine their inner workings. One of the most enchanting aspects of these objects is the way the eyes of the skeletons and demons appear when the cards are backlit. The eyes (and other details, such as flames and chandelier candles) glow red or green. This is because in the locations of these details, the albumen print has been pierced through and backed with a translucent, colored substance resembling hard candy in appearance. I found references in the literature for these works in which this material was described as “animal glue” and “resin,” but it was unclear whether it had been characterized accurately. In most cases, the substance appeared as tiny, cutout rectangles, but there was also an example where the material (now hard and shiny) clearly had a liquid consistency when originally applied.

LACMA’s Conservation Center is fortunate to have a research department, and at my request, assistant conservation scientist Laura Maccarelli performed non-destructive Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis on the colored material. In both cases (cut rectangles and liquid), the substance was found to be animal protein, such as animal glue or gelatin.

Damage to art and cultural objects is lamentable, but conservation treatment to address this damage can provide rare opportunities to learn about an object’s hidden structure and material components. Understanding how something was made creates a connection between the object’s maker and us, as well as increases our appreciation for the object. We learned that two different methods were used to apply the colored gelatin (as solid rectangles and as a liquid, using an extra tissue layer). Could the different production methods be linked to different workshops? Discoveries always inspire new questions.

With the night of trick-or-treating upon us, I can say that this project was a real treat. It was a joy to see the inner workings of the Diableries, and to devise a treatment that would be invisible in transmitted light, allowing the skeletons and demons to glow in all their eerie, spooky glory.

Watch this special video of Brian May viewing some of the Diableries that were on view in 3D: Double Vision and see how these stereographs come to life in vibrant and ghoulish shades. Happy Halloween!