This three-part series of Unframed articles teases out pictorial details related to the black figure with the pearl earring in Jan Havicksz Steen’s 1668 painting Samson and Delilah. Seeking to unravel the layers of social relations and hierarchies gestured at in the 17th century Dutch painting, three questions serve as roadmaps throughout the series.

- Why is there a black figure behind one of the painting’s protagonists?

- Why is this figure wearing a pearl earring?

- Where did the pearl earrings seen by Steen originate?

Where did the pearl earrings seen by Steen originate?

This series began with tracing visual mysteries apparent in Steen’s painting. What is equally as interesting is calling into question where the pearl earrings depicted by Steen originated. To that end, this article concludes with an examination of the Dutch Republic’s imperial operations in pearl excavation.

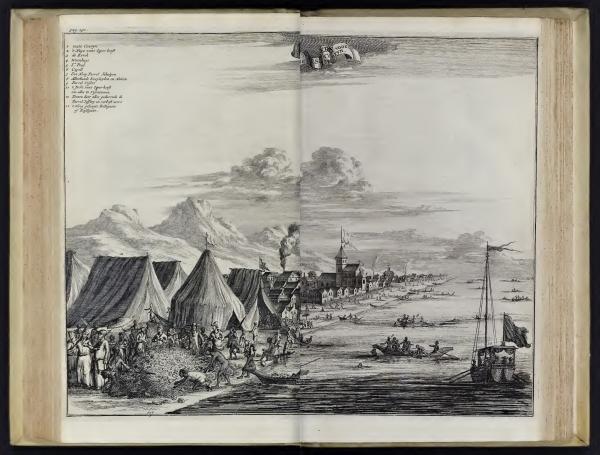

The image above is a tool to investigate these imperial administrations. The image is set in the coastal town of Tuticorin, named Thoothukudi as of 2018. Thoothukudi is situated in the Tamil Nadu region of India and borders the Gulf of Mannar, a body of water between southeastern India and western Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon). Johan Nieuhof’s anthropological drawing displays an important activity in this coastal area: pearl fishing. The drawing illustrates divers parsing through oysters to find pearls as well as other divers in a boat returning to the shore from collecting oysters in the middle of the Gulf. The image also includes Dutch men with weapons in their hands watching over the divers.

The scene is a visual documentation of the Dutch East India Company’s imperial presence in South Asia. At the same time as the Dutch West India Company established slave trade posts in Western Africa, the Caribbean, and South America in the 17th century, the Dutch East India Company governed pearl fisheries off the Gulf of Mannar. In 1658, the Dutch seized the Portuguese government’s control of pearl fisheries across the Gulf. The Dutch East India Company imposed taxes on local divers, deducted tribute (i.e., pearls) from expeditions, and frequently used violence to regulate locals’ behavior at the various fisheries. Samuel Miles Ostroff, in his 2016 dissertation “The Beds Of Empire: Power And Profit At The Pearl Fisheries Of South India And Sri Lanka, C. 1770-1840,” notes that the Dutch taxed diving stones (key equipment for pearl fishing) on a “a three-tiered system: “Christian,” “Heathen,” and “Moor” (17). Moor, in this instance refers to Muslim individuals. Christian divers paid the lowest tax rate and Muslim divers paid the highest. Ostroff later quotes Governor Hendrick Becker of Dutch Ceylon declaring in 1716 that “The tax on the stones is regulated according to the character and position of the divers” (108). The prejudicial and subjective stone taxation criteria are examples of how the Dutch East India Company institutionalized their imperial values and rules in the context of pearl fishing. Pearl fishing also took place in the Caribbean with the Dutch West India Company in places like Curaçao, a Dutch slave trading post beginning in 1672.

The Dutch’s involvement with pearl fisheries, and the global pearl market more broadly, centered on a high risk activity—pearl diving—which involved the diver descending into the middle of the Gulf and using tools like a stone, rope, and a basket. Scholars Natarajan Athiyaman and K. Rajan in “Traditional Pearl and Chank Diving Technique in the Gulf of Mannar: A Historical and Ethnographic Study” (2004) outline the traditional pearl diving technique in detail. Diving required knowledge of not only the diving technique, but also of the local body of water. Additionally, securing oysters with pearls was not guaranteed at any given time.

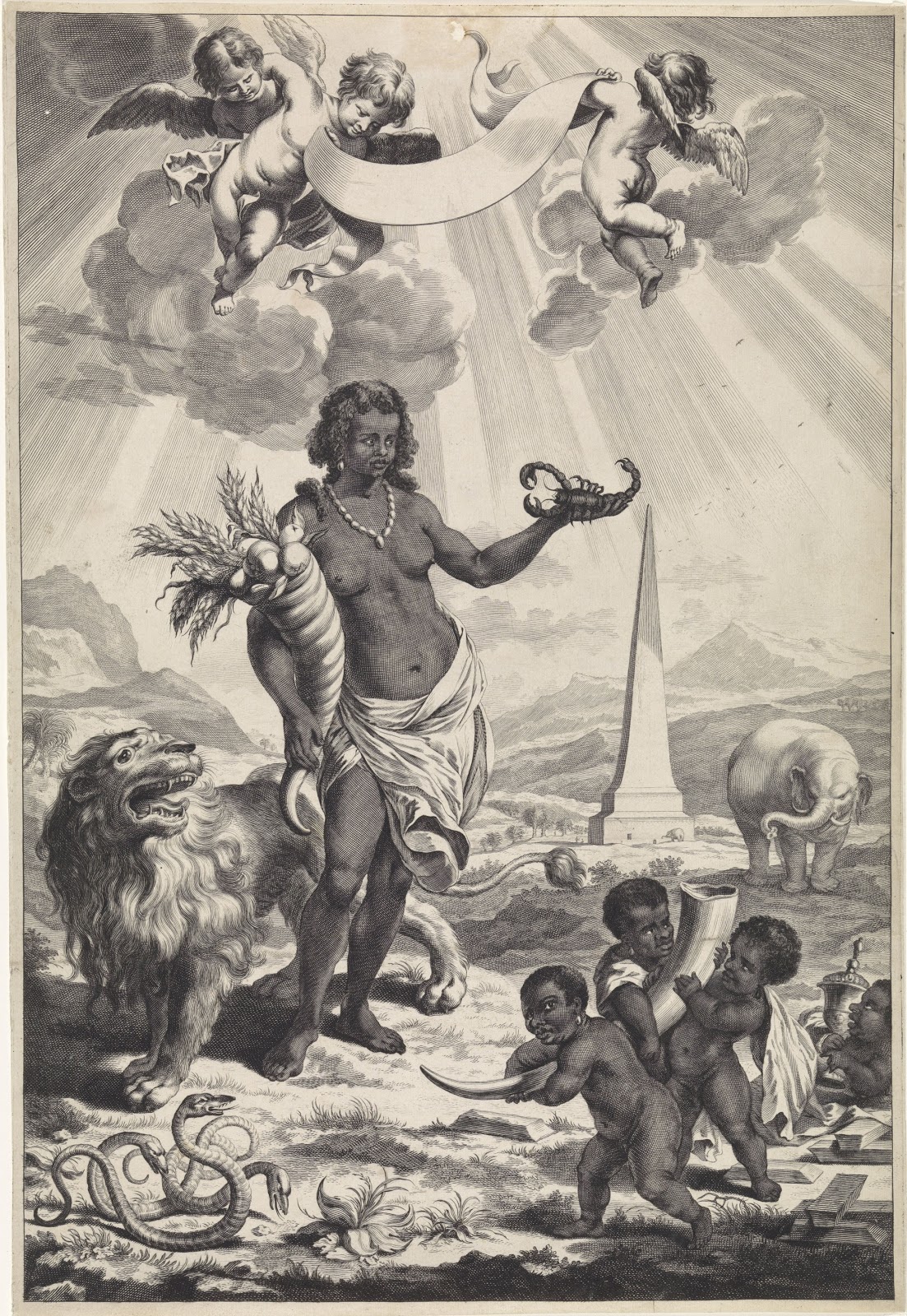

The pearls in Dutch artworks, not limited to those worn by black subjects, cannot entirely be traced to a particular place or type of diver. The pearls could be figments of the artists’ imaginations. Importantly, thinking about pearl excavation in artworks such as fig. 10 generates inquiries about the pearl as a symbol and its relation to the body it is associated with.

Molly Warsh’s words in American Baroque: Pearls and the Nature of Empire, 1492-1700 (2018) captures the essence of this new understanding. Warsh writes in regards to the ubiquity of pearls in Spanish society, “Pearls brought their bearers a piece of imperial drama: proximity to exotic people and places and the violence and death in the quest for overseas wealth” (81). Imperial drama within the Dutch context could reside in both the Dutch defeating the Portuguese in a war over the Gulf of Mannar and the risk involved in the pearl diving technique itself. It is unclear if all Dutch citizens who wore pearls knew of the pearls’ origins, yet the labor, business, and bureaucratic histories of the pearl still exist regardless of the wearer’s knowledge. That said, the symbol of the pearl becomes not only of wealth in some cases, but specifically of colonialist vanity. This vanity privileges the thrill of war and adventure required to gain the pearl over the inequities exacerbated and lives lost due to the colonial pearl fisheries.

%20(1).jpg)

Discussion of pearl excavation also encourages audiences of Steen’s painting, and Dutch artworks more generally, to consider the unseen colonial, labor, and social conditions tied to pearls and other objects depicted in art. The pearl on black characters in paintings like Jan Steen’s painting Samson and Delilah provoke larger questions about Dutch society in the 17th century. Would black figures in the Dutch Republic and across Dutch colonies have actually worn pearls at the time? Would these individuals have understood the pearls’ origins? If so, did they specifically understand them as originating from the work of a Sri Lankan or Indian diver? What did any Dutch person know about the origins of their commodities at all? What did black people in Dutch society and Dutch colonies know about the indigenous South Asian divers who interacted with Dutch workers and bosses at the fisheries?

This series began with a question and will end with a multitude of questions. One of the intrigues about an old master painting like Samson and Delilah is the ability to get lost in the mystery of subjects who are, in the words of former LACMA Mellon fellow Lauren Churchwell, “hidden in plain sight.”