Last year, 2019 Art + Technology Lab grant recipient Eun Young Park began her project, Radical Soft Robots, which examines the artistic possibilities of “soft robots,”—robots made with soft materials including silicone, vinyl, fabric, and paper. Inspired by the use of inflatables by utopian artists of the 1960s, the artist aimed to produce prototypes that LACMA visitors could engage with. In the face of current pandemic travel restrictions, the Helsinki-based artist adjusted her "half-time" presentation into a report where she would have the opportunity to discuss the process rather than the outcome. Already Park's approach and ideas have shifted as her project has evolved, which she believes is quite natural in pursuing an artist project. What follows are her trials, errors, and new directions she has taken over the past year.

Why soft? Why radical?

Above all, I feel the need to elaborate on the title. What is a soft robot and why is it/should it be radical? Soft robots are robots made with soft and flexible material. If you come up with an octopus-like silicone robot, or a big white Baymax from Big Hero 6, they are both part of this family. In the field of soft robotics, the researchers are concerned, as far as I understand, with increased safety and flexibility issues, when compared to traditional robots made of rigid parts, in operations where softness is needed—for instance, in the health industry. However, what I found interesting was their unconventional approach to robotic materials and technology, and the use of craft techniques such as paper folding and fabric manipulation.

In my previous projects, I have actively adopted movement, in product design or art installations, with an interest in the choreography of objects and composing the movement in time. Movement, with the aesthetics and rhythm of its own, evokes emotion, makes static and mundane things alive and playful, and furthermore adjustable. No wonder the possibility of using soft materiality and subtle movement instantly fascinated me. In soft robots, I saw a possibility for artistic exploration. Simply put, doesn’t it sound cool that materials and techniques used for the making of pleated skirts and origami paper cranes can make robots?

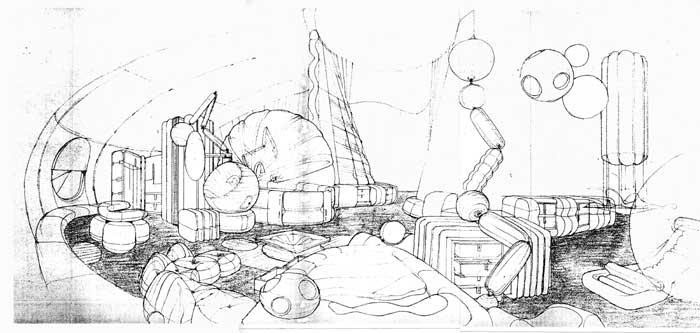

A pneumatically driven soft robot is not a concept that just emerged today, it dates back to the 1950s. It was not only engineers, but also artists and designers who were interested in the soft inflatable forms. In the 1960s, the mobile, ephemeral, low-cost, light-weight characteristics of inflatables resonated with avant-garde artists and architects of the time widely¹. Notable is that they used the inflatable as a critical and radical medium to protest against the rigid society and the discipline’s tradition. When I call it “radical,” I draw on their practices and understand the potential of soft robots as an expressive and critical medium that goes beyond the sphere of engineering.

About Being Soft and Slow in Technology

Robot, by definition, is a machine that is capable of performing complex actions automatically and independently. Robots help and serve humans by taking on hard labor on our behalf or by assisting us with their intelligence. In typical robots we know of, their efficiency and functionality is important, often associated with physical strength and agility. Notwithstanding the lingering fear that robots will outsmart us and take our jobs some day, they were conceived to serve us. If this is the case, what is the point of a robot, or technology in general, being soft and slow, thus being susceptible and weak?

Art historian Max Kozloff, while talking about soft materiality in sculpture, says that if sculpture has any pretensions to the mainstream, or any claim to historical necessity, it is not allowed to be soft². According to him, softness is about change, deterioration, and surrendering to the natural condition, thus it is anthropomorphic and mimicking life itself. Being soft is to exist, to be in company, to reveal, to amuse, to create an atmosphere, and to give us a moment of reflection³. Softness not only involves materiality but also change, the presence of time that is not so visible, but subtle and slow. Take flowers blooming, leaves sprouting, pets in your lap sleeping and breathing, curtains fluttering in the wind. Technology can act on an indistinct environment and on our emotions with aesthetic and affective goals over efficiency. Finally, this train of thought led me to wonder: what if a robot is a plant, a wall, a hat, a dress, an armchair, or a pillow?

Stay tuned for Part 2 of Eun Young Park’s mid-term report when some of the prototypes from Pillow Study will be explored in greater detail. This project was made possible by LACMA's Art and Technology Lab Grant and was partly funded by an Aalto ARTS Grant. The work spaces and facilities were supported by Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture.

The Art + Technology Lab is presented by

The Art + Technology Lab is made possible by Accenture, YouTube Learning, and Snap Inc.

Additional support is provided by SpaceX.

The Lab is part of The Hyundai Project: Art + Technology at LACMA, a joint initiative exploring the convergence of art and technology.

Seed funding for the development of the Art + Technology Lab was provided by the Los Angeles County Quality and Productivity Commission through the Productivity Investment Fund and LACMA Trustee David Bohnett.

¹ Architectural League of New York, The Inflatable Moment: Pneumatics and Protest in '68, Princeton Architectural Press, 1999.

² Max Kozloff, extracts from "The Poetics of Softness" in Materiality, edited by Petra Lange-Berndt. London: Whitechapel Gallery; Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2015.

³ Hallnäs, L., Redström, J. Slow Technology – Designing for Reflection. Personal Ub Comp 5, 201–212 (2001).