October is Filipino American History Month, a time to acknowledge and celebrate both the historic and modern-day contributions of "Fil-Ams" to American society. People from the Philippine Islands first arrived on the continent in the 16th century and have since enriched American life, from the arts to agriculture. They have labored as early farm and factory workers, served in our military, taken part in the Zoot Suit Riots of the 1940s, and led, with Chicanos, the agricultural workers rights demonstrations of the 1960s and 1970s. Today, a significant number of Filipinos serve as front-line health care workers amid a pandemic. Arizona State University Graduate Fellow and Art History Master's Candidate, Matthew Villar Miranda, reflects on his/their LACMA-ASU Master's Fellowship in Art History and how Philippine identity has shaped his/their academic practice through a conversation with Clarissa M. Esguerra, Associate Curator of Costume and Textiles at LACMA, curatorial mentor to Matthew, and fellow first-generation Filipinx American.¹

Clarissa Esguerra: How did you find out about and get involved in the LACMA-ASU Master's Fellowship in Art History Program?

Matthew Villar Miranda: In 2018, I was working as a Sales Supervisor at The LACMA Store and learned of the LACMA-ASU Fellowship's model of integrating hybrid and remote instruction into a full-time museum work schedule. I had spent some time freelance writing for a few art galleries and artists in Los Angeles and was looking for ways to immerse myself in an environment that could both refine and critique my writing while maintaining an income.

CE: What was it like working at The LACMA Store?

MVM: I was aware of my role as a public-facing service worker. I worked in the service industry while an undergraduate in college, after I graduated, and up until I began this fellowship. In these spaces, and especially at The LACMA Store, I developed a community of peers who to this day are still my core support system. Customer service language often teaches us to acquiesce to the assumptions and desires of the patron. As retail workers, we recognized that our images were just as much a part of the retail landscape as the postcards, ceramics, and catalogues on the shelves. Cognizant of this, we cared for each other, developed defenses against any microaggressions, and recognized our shared emotional labor. The idea and positionality of "servicing" deeply inform my core values of labor and class.

CE: What sparked your curiosity in particular pieces of the permanent collection?

MVM: Each of the objects in the store needed a proper justification for its sale that related to the museum's current programming. I thought deeply about how I could integrate the knowledge I had accumulated as a student of art history into the regular and daily consumption at The LACMA Store. I thought about objecthood and commerce as an opportunity to think deeply about objects—their production, design philosophy, materiality, and use-value.

As a retail worker searching for the value in their own labor, I thought of myself as a guide for the consumer to realize their own museum shopping as a kind of public participation in broader art economies. In all its romance, and in the best of circumstances, I wanted to deepen the relationship a consumer had with the thing I was selling them in a way that inculcated in the customer the sincere values I hold in creative communities.

CE: I appreciate how you've highlighted the importance of this public-facing role in the museum. How did you come to find out about the artist Alfonso Ossorio?

MVM: I was fascinated by the range and number of art postcards we had on sale at the store. In many ways, it visualized the "encyclopedic" ethos of LACMA and it very much advertised that one could find any object, ancient to contemporary, East to West, in this collection. An opportunity arose to offer suggestions for new postcards for the wall.

Given that Los Angeles is home to the largest number of Filipinos in the United States, I searched the museum's online collection database for "Philippine"/"Filipin*" and found a very small selection of objects that were associated with the Philippines. Among these objects there were a number of works by Alfonso Ossorio, a gay Filipino American artist who had lived through critical periods in the American avant-garde. His work was really the only works at LACMA that were authored by a "fine artist" of Philippine descent, and as such, the only works that had some degree of intentionality, self-possession, and agency afforded to the other artists represented in the store's top-selling postcards (Chris Burden, Andy Warhol, Henri Matisse, etc.).

CE: Ossorio clearly resonated with you as he has become the subject of your master's thesis at ASU. Can you speak more about what drew you to his work?

MVM: We share similar identities and embodiments. I felt compelled to learn how a queer, Filipinx American artist who inhabited overwhelmingly white, elite spaces found the resources and vitality to produce work and gain visibility. Studying his life and expression would allow a possible model for diasporic survival in a largely eurocentric and homophobic society.

He has made novel artistic and intellectual innovations to Surrealism, American Regionalism, Abstract Expressionism, and postwar assemblage, but is primarily known for his relationship to more celebrated artists such as Jackson Pollock and Jean Dubuffet. It is Ossorio's incredible contributions but gaps in the canon that motivate me.

CE: As part of the LACMA-ASU Fellowship, the students select a mentor. I was so pleased that you selected me to fill this role. Though I am not a specialist on Ossorio, may I ask why you sought my mentorship?

MVM: Other than fashion goals, the exhibition you co-curated in 2016, Reigning Men, was a massive influence in the ways it expanded my ideas of what topics are worthy of academic and museological attention, while also rethinking standard exhibitionary strategy into conceptual themes rather than chronology and periodization. It was a very flamboyant, awesomely queer show that articulated fashion as knowledge, performance, speech, and drag that made me want to take ownership and pride over my own self-presentation. I started to wear mesh, cropped tops, and ripped denim to work at the exhibition shop; and in the usual instance where my queerness would be read as unprofessional—with the weight and justification of Reigning Men around me—I thought to myself, "There is no better uniform. lol."

In an early seminar for the Fellowship at LACMA where we first met, I felt an immediate affinity to the way you spoke about your personal background as a first-generation Filipinx American specializing in Western art histories. I knew that our drives were in similar places when you acknowledged the large representation of Fil-Ams working in the museum at the front and back ends and yet having few objects that reflect our community on the walls. We shared the sentiment that we could not isolate our personal identity and public responsibilities from our professional work, and like many Fil-Ams, understanding the full dimension of this requires extended and committed autodidactism and (un)learning outside of the academy, the gallery, and the office. It heartened me to know that you were doing work inside and outside of LACMA to promote Philippine cultural production in Los Angeles.

CE: I too felt an affinity to you. As a curator, we continue to learn, and I feel that our conversations about our field, shared identity, and how we must continue to grow the canon of art history and critical thinking in American museums have positively impacted my own curatorial practice. Also, I can't tell you how happy I am that Reigning Men could serve as a form of justification for your work uniform!

MVM: Yes, the spring and summer of 2016 were the height of my workwear OOTDs. I also deeply appreciate how your work outside of LACMA centers Filipinx artists and designers. Last year, you introduced me to PULO Project. How did it begin?

CE: PULO Project is an art and fashion collective that promotes contemporary Philippine art and design. It was the brainchild of fashion designer, Michelle Aquino, who curated and held the first iteration of PULO Project at the downtown L.A. concept fashion and art boutique, Please Do Not Enter, in collaboration with its founders, Emmanuel Renoird and Nicolas Libert. It was amazing to see a space focus solely on contemporary Philippine art and design.

MVM: This past spring, you also introduced me to Linda Nietes of Pinta Dos Gallery and Philippines Expressions Bookshop. For the first time in my life, I was able to see Philippine Indigenous artworks from rattan baskets, ikats, Ifugao bulul (carved figurines), and duyu (ritual hardwood bowls). It was significant to me that such art was not made accessible to me through a museum but through a small independently run community space.

CE: Oftentimes, curators of all fields and disciplines find artworks through spaces like galleries which are more nimble in their display. And in the past, there admittedly has not been an emphasis to collect Philippine artworks. However I hope to work towards changing that.

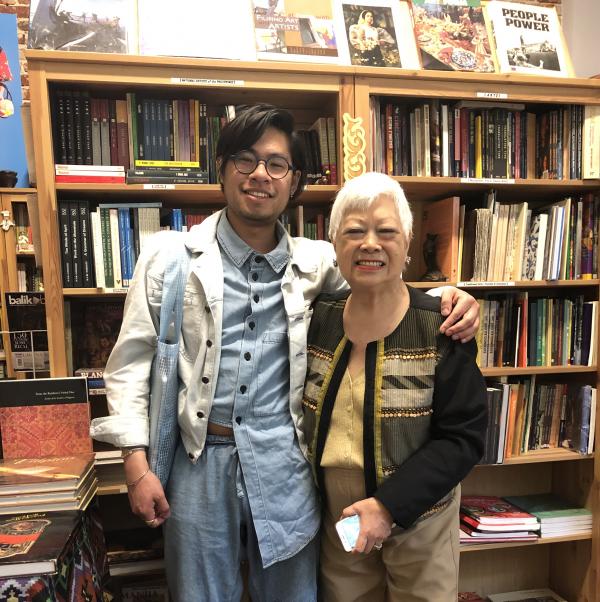

I was lucky to meet Linda through Michelle and the Philippine Consulate. Ms. Linda's Philippines Expressions is the only Philippine bookstore in the L.A. area, and it is such a treasure trove of research materials and sources of inspiration, much of which are very difficult to find in local libraries. In addition, she has a gallery where she regularly highlights Philippine art and artists. I was so pleased we were able to visit her and see her personal collection, on display at the time, just before the COVID-19 Safer at Home Order.

MVM: I admire Ms. Linda's role in keeping independent and radical writing alive when Marcos's Martial Law actively suppressed dissent in the Philippines in the 1970s–80s, and how she continues to support Fil-Am artists and writers by creating new centers of literature and art spaces in L.A. after relocating here.

How do we envision LACMA better representing and supporting L.A.'s Filipinx population?

CE: There is more work that needs to be done in building the representation of Philippine art in our collection. Though collecting and exhibiting is a relatively slow and careful process (as it is with all objects acquired), my hope is that one day the display of such artworks will increase a broader awareness of the arts of the Philippines while engaging with our community and supporting current and future generations of Filipinx researchers and artists.

Matthew, you are now in your last year of this Fellowship. Could you reflect on your fellowship, thesis research, and work now at the ASU Art Museum and how it has impacted how you will move forward in the museum world?

MVM: This year has been among the hardest in my life, and the long periods of lived self-quarantine and televised pandemonium has caused me to untether my self-worth from my career. The pandemic and uprisings in defense of Black lives has sharpened language around what constitutes essential work, community advocacy, and meaningful action. Large museums and galleries have been historically disconnected and complicit in these stratifications. But I do still believe artists and curators, broadly defined, do the work in picturing what it looks like when idealism meets radicality.

¹ The term "Filipino" is historically defined as a non-gendered identifier of a person from or a descendant of the Philippines. However, in recent years, the term "Filipinx" has been adopted in North America as a way to acknowledge identities beyond the gender binary, modeled after the "Latinx" movement.