*Throughout this article we refer to Hawai'i as a nation. On January 16, 1893 the Hawaiian Kingdom was invaded by United States marines which led to the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government the following day. We, like many people around the world, view Hawai'i as a sovereign nation state that is illegally occupied, and fully support Hawaiian sovereignty.

As LACMA's Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Blackburn Project comes to an end, we would like to share more about the stewardship process and the external relationships and communities that have been essential in the development of this project. We recognize that without our Advisory Board's help, knowledge, and perspective we wouldn't be able to share this project with you. Following the lead of museums in Aotearoa (New Zealand) and Hawai'i, LACMA used this project to integrate external expertise and Indigenous knowledge at the museum. We were fortunate to be part of the great team responsible for bringing this project to life and would like to thank all of our colleagues for their support and guidance. We joined LACMA's Collection Information & Digital Assets (CIDA) department for this project and have spent the past two years digitizing, uploading, and researching the Mark and Carolyn Blackburn Collection of Photography.

Some of the questions we have wrestled with during the past two years are:

- What impact can grant projects have at a museum?

- How can we evaluate the success of the implementation of a project?

- Is success based on predetermined objectives or should we also consider the impact of lessons learned along the way and how they affect the museum?

- Have we gained an understanding for a better approach to Indigenous collections?

- Can we sincerely say that the Blackburn Project has brought insight to LACMA's future approach when working with Indigenous collections?

- What is the importance of having an Advisory Board?

Researching and Digitizing the Blackburn Collection

Luz Maria Mejia Ramos, Collection Information Technician

In 2015, LACMA acquired the Blackburn Collection and in 2018 was awarded an IMLS grant that was originally pursued by the former head of CIDA, Maja Clark. The main objective was to highlight the historical collection within LACMA and ultimately to provide access to it through a digital platform. The Collection contains over 9,700 diverse Oceanic photographs, stereographs, albums, cartes de visite, lantern slides, ephemera, and even a surfboard; which date from 1840 to 2016. To date we have found out that 4,784 photographs are of Hawai'i, 1,685 are of Tahiti, 982 are of Sāmoa, 682 are of Aotearoa, 634 are of Fiji, 214 are of the Cook Islands, 143 are of Tonga, and 619 are currently unknown. Some other locations within the collection that we haven't been able to quantify are Rapa Nui (Easter Island), New Caledonia, Australia, Marquesas Islands, Solomon Islands, and the Philippines. In a previous publication of Unframed—Researching the Blackburn Collection, Part 1 and 2—Sedna Villavicencio introduced some of the research results and additional information about the represented nations. The Collection is so extensive, rich, and complex that this grant allowed for an opportunity to fully dedicate the hours and focus it required; with the understanding that significantly more time would be needed to research every object.

Once the grant was awarded, the intense work was spread across different departments within LACMA. Registration and Collections Management spent several months in the former Study Center for Photography and Works on Paper where Hema Panesar was fully dedicated to cataloguing, processing, and rehousing each one of the objects that entered the collection. Initially, the objects were placed inside wooden drawers, separated in broad topics like “Hawai'i,” “surf,” etc; each item was then identified, measured, described, photographed, and stored in folders, mylar sleeves, and ultimately, archival boxes. Conservators regularly visited the Study Center to assess the condition report of specific objects, identify the material, and evaluate the state in which objects arrived in the collection. Every step was done in a methodical manner including capturing the information in LACMA's Digital Assets Management System (DAMS). The objective of processing between 5,000 and 6,000 objects to reach the grant goal drove us to work almost to a batch production.

The next step was digitizing the objects with a Nikon DSLR camera, through a consistent, high-quality setting designed by Senior Imaging Specialist and Photographer Yosi Pozeilov. The image capture was done through a wireless device that was controlled by a tablet. The process for each object consisted of placing the photograph in front of the horizontally mounted camera, next to the color bars, scales, and object's id. Then the camera stand was adjusted according to the size of the object. Due to the timeline of the grant and the amount of images that needed to be digitized, early on in the process it was decided that the materials would be imaged according to similar sizes, which would prevent the constant adjusting of the camera stand.

As a Collection Information Technician, the greatest challenge we faced was reaching the number of photographs that were required to be digitized for the grant and packing all the objects for storage in preparation for construction of the new building for the permanent collection. Despite thinking that this was going to be the hard part, we reached and surpassed the objective by digitizing about 9,000 photographs. The process was essential for the preservation of the objects and for the collection to be able to be shared in a publicly accessible, open platform.

Once the items reached the digitization phase, the responsibility shifted from the physical aspect of the object to the essence of the object. The elements that are represented within the collection are so complex. There are everyday life images, ceremonious images, and others that require research to learn the historical context of how these photographs were taken. Part of the process that was not included in any of the workflows—how do we respectfully approach every item of an Indigenous collection when it has already been subjected to the impact of colonialism? We now recognize that this part of the project needed more attention as a result of listening to the relationships that are being developed inside and outside LACMA as part of the following phases of the project.

Through the Blackburn Collection, LACMA is trying to make a difference in the steps that need to be taken when working with Indigenous collections. The museum is showing the willingness to learn from, while collaborating with, an external advisory board with representatives of some of the cultures that are depicted within the collection. Each one of the members is an expert in specific locations and in specific fields—all of them have in common their work in cultural heritage material and in the work they have done with communities. There is still so much to learn about working with an Indigenous collection. Every collaborator has shared their expertise and knowledge, and without a doubt having the advisory board and a dedicated researcher was a huge addition because of the approach and knowledge that was added to this project.

The Blackburn Advisory Board

Sedna Villavicencio, Blackburn Research Assistant

As research assistant, the part of the project I was most excited about was the advisory board portion. When writing the grant, CIDA recognized that more than one researcher would be essential for examining over 9,700 photographs. Acknowledging that the Collection is overwhelmingly of Indigenous peoples, their culture, and their land, LACMA wanted to prioritize Indigenous perspectives. Additionally, we hoped the advisory board would help point out some of LACMA's blindspots or biases we may have regarding the Collection. One way to collaborate with these stakeholders was to create an advisory board representative of different Pacific Island/Oceanic communities. We planned to have advisory board members from Hawai'i, Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, Aotearoa, Cook Islands, and Tahiti (the main nations in the Collection) to lend their expertise and knowledge. We thought of creating the advisory board closer to the end of the grant period (November 30, 2020) so we could have more of an understanding of the entire Collection. Our goal was to have three meetings (each around two–three hours) where the advisory board would review photographs, help identify people and places, and advise LACMA on what photographs are appropriate for sharing online. Like with many project proposals, our advisory board's planned composition and advisory role has shifted.

We began our advisory board with Blackburn Project consultant and Blackburn Advisory Board Chair, Joy Holland. Joy currently serves as Associate Librarian at the UCLA American Indian Studies Center. Before coming to UCLA, Joy worked to perpetuate community narratives and collections as Executive Director of Kona Historical Society (KHS), a Smithsonian Affiliate museum in Hawai'i. As a Hawai'i local, her knowledge of the Collection was indispensable. She helped with Hawaiian terminology, created a Hawai'i historical timeline and helped identify historical people and places. She began searching for members by contacting her colleague Stu Dawrs, Senior Librarian of the Pacific Collection at University of Hawai'i—Mānoa's Hamilton Library. Stu agreed to serve as vice-chair of the advisory board and together, Joy and Stu began work on a diverse list of potential members, each of whom had either cultural or professional ties (and often both) to one or more of the places depicted in the Blackburn Collection.

One invaluable learning experience for LACMA was understanding Indigenous protocol for reaching out to potential advisory board members. Like many Western institutions that seek expedient and punctual projects, LACMA was eager to begin meetings and adhere to typical administrative procedures and timelines. We mentioned this to Joy, and since we were strangers to all of the potential members, Joy recommended we wait until she and Stu speak to everyone personally. Joy let us know that many of her contacts would prefer to speak to someone they know personally before speaking to LACMA staff. Within a couple of weeks, everyone on our list had accepted our invitation to join the advisory board. In addition to chair, Joy Holland and vice-chair, Stu Dawrs, our advisory board members are:

- Cristela Garcia-Spitz, Digital Initiatives Librarian and Melanesian Specialist at UC San Diego Library

- Juliann Anesi, Assistant Professor of Gender Studies at UCLA

- Fran Lujan, Director of the Pacific Island Ethnic Art Museum in Long Beach

- Deborah Dunn, retired Curator and Director of the Mission Houses Museum & 'Iolani Palace in Hawai'i

- Justin Maga, Territorial Librarian at the Feleti Barstow Public Library in American Samoa

- Whina Te Whiu, Museum Curator at Te Ahu Museum in Aotearoa (New Zealand)

- Pixie Navas, retired Cultural Historian & Archival Technician at Kona Historical Society in Hawai'i

- Daniel Akaka, Kahu and Mauna Lani Hawaiian Expert from Hawai'i

In addition to cultural knowledge and place-based expertise, our advisory board members have diverse professional experiences, including Disability Studies; management of Pacific-related museum, library, and archival collections; creation and maintenance of online photography collections; physical preservation of library and museum materials; and community outreach. After two successful meetings in October, we have been able to learn more about the advisory board members' backgrounds and experience working with Indigenous communities. During these meetings, the members defined their role as an externally constituted advisory board, in relation to LACMA and the grant. Rather than tell LACMA what photos can or cannot go online (excluding sensitive photos) or conduct in-depth research, the advisory board's role is to support and advise on potential policy, information resources, appropriate contacts, and best practices in relation to a collection.

The advisory board will also seek to provide LACMA with a broad framework for working with communities to facilitate and ensure access to the Blackburn Collection, and other collections, in a culturally sensitive and inclusive manner. An excerpt from the advisory board's draft statement of function encapsulates its role:

“As advisory board members, we seek to encourage relationships between LACMA and Indigenous communities depicted in this and other museum collections. We acknowledge that Indigenous people and community members are the experts in collections and in photographs depicting their culture and landscapes, and museum professionals should act as caretakers. We view advisors as a potential bridge between the museum and the communities depicted, with a dual role of supporting Indigenous communities while providing valuable insights to the museum.”

We fully support our advisory board and agree that the only experts in Indigenous collections depicting their culture, landscapes, and ancestors are the Indigenous communities themselves and the people they trust. We have learned that many photographs of landscapes or landmarks trigger memories from our advisory board members. For example, when we showed them what we thought was a photograph of a random waterfall, we were immediately informed it was Waiānuenue, Rainbow Falls in Hawai'i. Community members have knowledge that we as outsiders do not and these collections benefit greatly from their perspectives.

Some important questions the advisory board has asked are:

- After the grant cycle is done, who at LACMA should be charged with monitoring the site?

- After the grant, relationships with these communities will need to be fostered somehow. Who at LACMA will be responsible for this outreach?

- The museum has shown an interest in engaging with communities depicted in this collection. How might it pursue this goal?

- Can the "comment" feature be enabled on the Collections Online website to gather community sourced information?

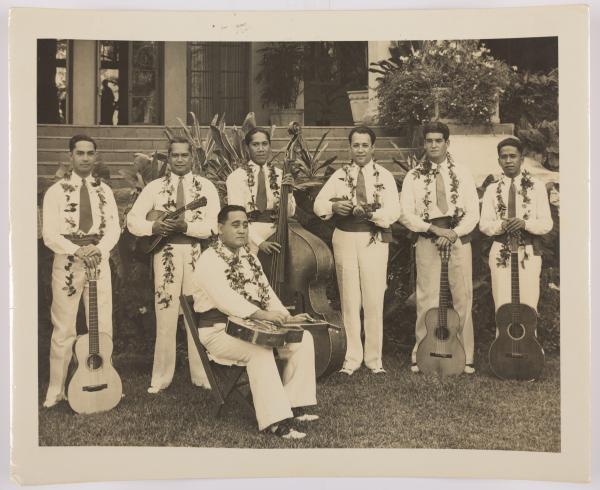

.jpg)

The advisory board has taught us more than we could have anticipated. During our first meeting, a member inquired if LACMA staff had asked ancestors of those depicted in the photographs for permission before scanning and digitizing photographs. We appreciate our advisory board members allowing us to make these mistakes and learn from them, as well as being here to hold us accountable to their relatives, ancestors, and future descendants. During our final meeting, members met privately for the first two hours then invited LACMA staff to the last hour. During our time together we spoke about different online platforms for the Collection (e.g. Digital Pasifik, Digital New Zealand) and how to engage with the public for information about the photos. A sentiment echoed by different members was how beneficial it is to have the public comment on photos. This is a way to have community members share their knowledge of specific landscapes or identify people in photos. Having a "take down policy" for certain photos was also recommended.

The advisory board aims to provide resources for LACMA such as: bibliographies, recommendations for timelines on deliverables, analogous policy handbooks, protocol brochures, language, and a document aggregating many of these references and recommendations. The members have agreed to work past the grant deadline, a level of commitment we could have never predicted. This experience has taught LACMA the importance of having Indigenous scholars and researchers at the center of conversations regarding collections depicting their ancestors. We hope the Blackburn Project can contribute to processes of healing and adopting community-minded practice already in motion at some of our peer collecting institutions, and we hope these practices will increasingly become the norm.