When did the moon and stars become such a routine backdrop in photographic portraiture? Do these paper-mache studio props stand in for our hopes and dreams, for the exotic, or for pure playfulness? Is it the juxtaposition—however, ahem, over the top—of the camera “knowing” a sitter who, in turn, hangs, draps or hugs the yet unknown specter of the moon? What convinced photographers that this was the backdrop that would lure every couple, young and old, every mother and child, every singleton, duo, family (and their pets!) to walk into the local photo studio? Spoiler: I’m writing this blog knowing there is no one definitive answer, and trust me, I’ve asked numerous collectors who focus solely on—wait for it—the moon.

There is but one image of a crescent paper moon and stars on view in the exhibition Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography, 1870–1900, but that one image is what set me on my unavoidable voyage. In this image, the photographer, E.R. Weston, poses himself in a rather minimal (you’ll see what I mean) iteration of a stand-up sized moon in a promotional image. The age of cabinet cards in America, 1870-1890, which continued in many regions into the 1910s, is synonymous with the concept and growth of the professional photographer, and to visits to the photographer's skylight studio. As alluded to earlier, photographers were a savvy lot and they deployed many such backdrops to encourage repeat visits; left to their own devices, many sitters prior to this time would allow themselves but one or two photographs in a lifetime. (That’d be birth and death, thank you.)

As evidenced in the images found in my research about the appearance of the moon in early photography, the gimmick really worked.

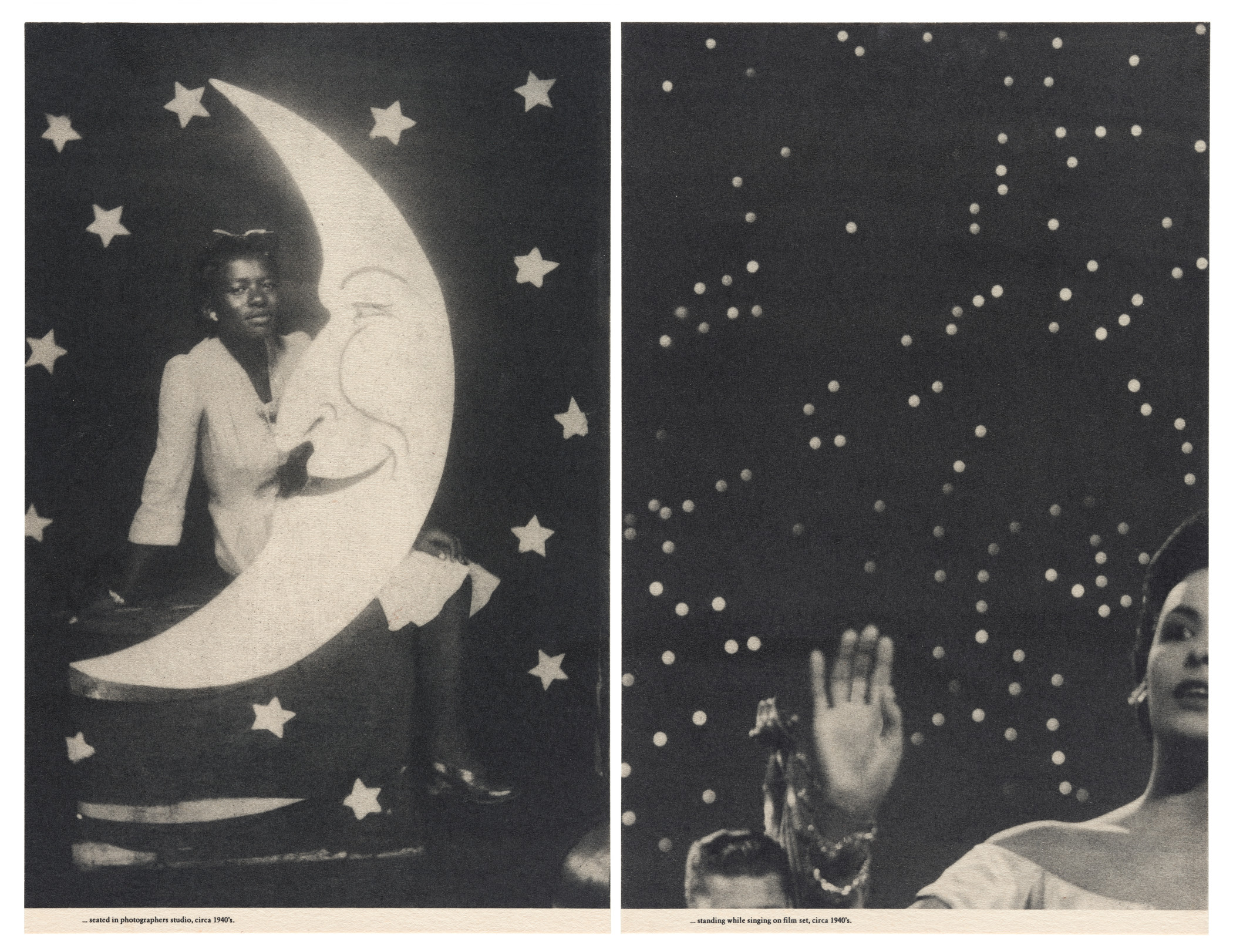

A diversity of sitters also appears, evidence of the democratic nature of the medium of photography. Anyone could, and was encouraged to, make photographs, and to make photography an integral part of their lives. Seeing and holding a likeness of yourself or significant others validated all Americans, regardless of class or skin color.

Now, I know all the film scholars, including newly minted ones fresh off a visit to the Academy Museum, will point to the seminal 1902 film, Le Voyage dans la Lune (A Trip to the Moon) by George Melies, as the substantive link. Appearing some thirty years prior to the cabinet card phenom, it’s a false lead. Jules Verne’s 1865 fantastical novel From the Earth to the Moon sparked a craze and definitely inspired Melies’ film, but it didn’t include imagery. What it likely did spawn, however, are interactive moon installations at World’s Fairs across the globe, which in turn were embraced by local entrepreneurial photographers.

With the stars perfectly aligned, for one day, Acting Out will overlap with the exhibition Black American Portraits, where we included a stunning Lorna Simpson diptych, which utilizes a found cabinet card on one side and a publicity still of Lena Horne, set against the stars, on the other. If you can, time your visit to see both exhibitions!

Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography, 1870–1900, is on view through Sunday, November 7, the same day Black American Portraits opens.