It’s with gratitude and enthusiasm that we announce the Art Here and Now (AHAN): Studio Forum artists of 2022: April Bey, Beatriz Cortez, Kate Mosher Hall, Greg Ito, and Kyungmi Shin.

AHAN: Studio Forum is a group of LACMA supporters who are instrumental in bringing the work of emerging and mid-career artists based in L.A. to the collection. On an annual basis, the curators of the Contemporary Art department organize a series of studio visits open exclusively to AHAN members. They reconvene at a later date for a discussion that leads to the final selection. Below, get to know the AHAN cohort of 2022 and their work through their recent conversations with Rita Gonzalez, Jennifer King, and José Luis Blondet.

Beatriz Cortez

Interviewed by José Luis Blondet

Your work often evokes sci-fi narratives to address current issues. Where does that fascination for utopian and dystopian worlds come from?

As I think of long temporalities, I try to imagine the logic of Western humanism, liberalism, and extractive capitalism as a brief moment in the life that is possible on this planet. I like to imagine other possibilities out of joint with time and space, outside this parenthesis in the life of the planet, in order to imagine other perspectives, other worldviews, but especially to imagine other possible futures.

Arguably, every artwork is a time capsule but the work just acquired by LACMA is a Time and Space Capsule. Tell us more about that.

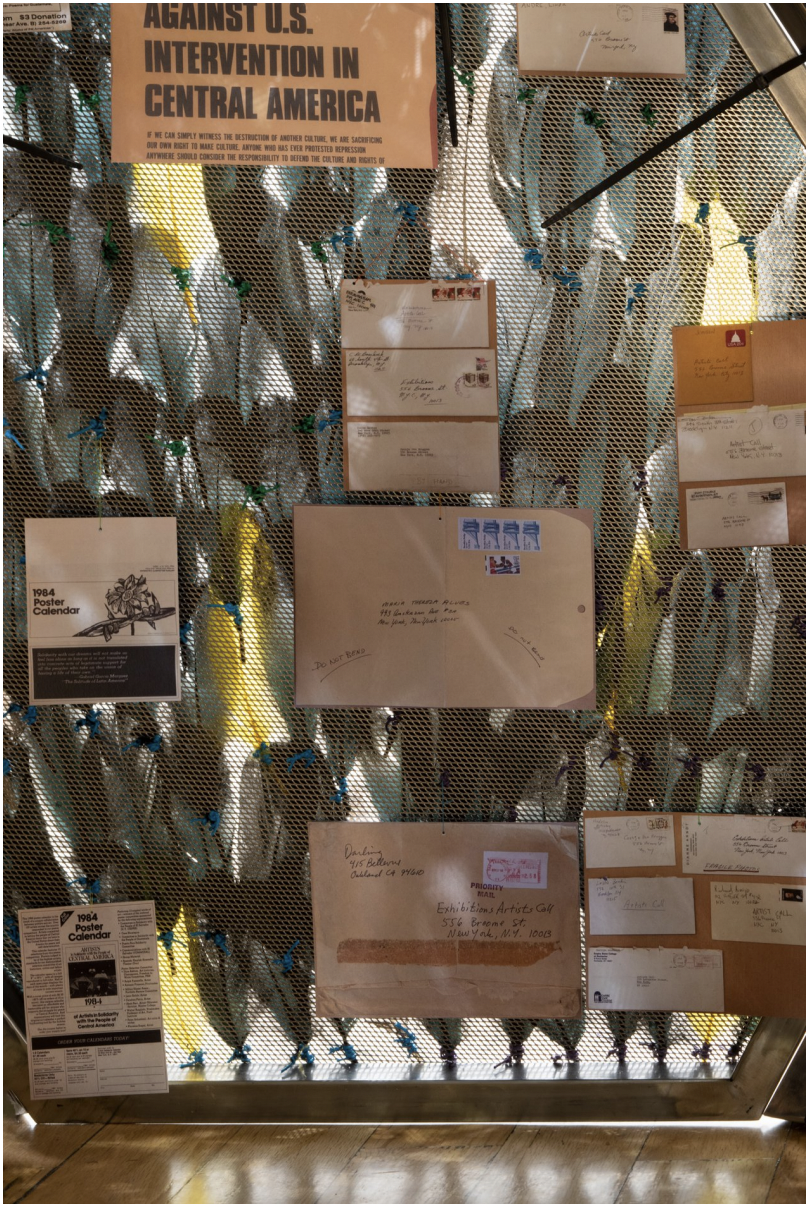

That is a reference to the idea that long shared conversations can be spaces that share a certain temporality, that generate a space-time, like a portal to another reality. To me, this feathered dome holds and brings together different precarious archives of a solidarity movement that emerged from within the artworld in New York, the crumbling of the revolution in El Salvador, and the history of migration and of immigrant labor in Los Angeles. I saw this juncture, the coming together of these worlds, as a space-time.

The work of artist and curator Coosje van Bruggen, a key collaborator of Claes Oldenburg not always properly credited, is sometimes overlooked. How did copies of her archive end up in your sculpture?

I went to research the archives of Artists Call at the MoMA Library. Artists Call was a solidarity movement in support of Central American peoples that emerged from within the artworld in the 1980s in New York, in the middle of the war in El Salvador, when I was 13 years old and still living there. Van Bruggen was integral to that project. I found these archives documenting her labor and the labor of many others trying to raise funds, create awareness, and stop U.S. military aid to Central America very moving. They made a warmer art world for me, they made the reasons for our migration visible, and they meant that others, many of them artists, cared about us, about our survival. I began the research thanks to the invitation of Abigail Satinsky and Erina Duganne, who were curating a show about Artists Call.

What about the feathers? They do provide a powerful contrast with the geodesic dome.

In ancient times, feathers were greatly valued. The feathers engage with Coosje van Bruggen's work, for her a feather was a symbol of writing, of intellectual labor. For me, a feather is also a symbol of systems of value outside contemporary capitalism. At this time, almost 40 years later after Artists Call, Central American immigrants who came escaping that war continue undocumented. As a community, we don't have access to treasures (or to quetzal feathers), we have access to goose feathers and guinea fowl feathers, which are considered common and used for crafts, and we have access to industrial materials like steel. The greatest gifts we have are our memory, symbolically represented by the archives that live within the dome—from the Artists Call project but also from my family and friends—and our labor.

Making that dome required intense labor on my part, by the artists working in my studio, our friends and our families, all of us stitching these feathers, reviving a cultural memory within ourselves as we learned how to stitch feathers over the steel mesh the way our ancestors did before us.

Kate Mosher Hall

Interviewed by Rita Gonzalez

To begin with, would you mind discussing how documentation of performance gets integrated into your work?

Performance is documented in my work by silkscreening, which inherently operates in a grid, and if anything in the process of making a silkscreen becomes misaligned then those marks are a sign of the body or something human. I like to think of subjectivity as a mesh net moving through time and whatever it collects or throws away is personal/specific. I love working with the limitations of silkscreening, in pushing the material to perform in different ways but always allowing spontaneity to slip in.

I would be interested to hear about how your past experience as a musician plays a part in how you approach your layered compositions.

Drumming helped me think about how rhythm, a beat, or repetition can have emotions. Even though I can be repeating “one, two, three, four,” I found that I can actually insert emotion and different touch to the repeating patterns. Similarly with the screen I can change the emotional range of an image by how I interface with the stencil, with paint and with my body. I am interested in how a painting can have different mechanical/emotional workings that the viewer then experiences as a composition. Maybe I think about different parts of the work in different time measurements. A song is literally a linear composition whereas a painting composition for me is more like a 3D hexagon and multiple timings.

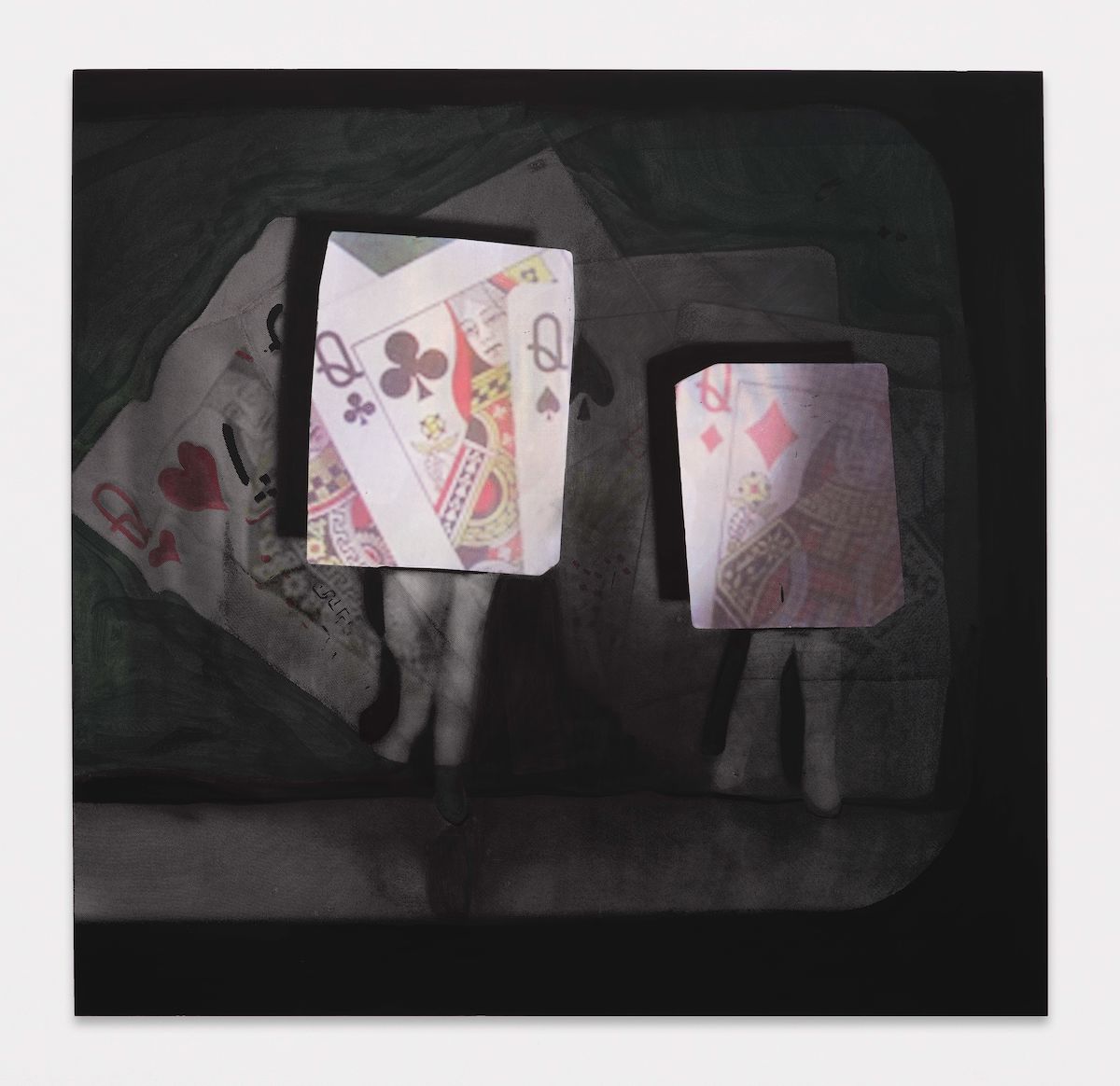

You have discussed the intense layering that goes into your screenprints, can you discuss the building up of the image in Luck?

Luck is an image of two people dancing on stage wearing boxes. The Queen of Clubs and Diamonds are projected onto the dancing boxes as the rest of the cards fall to the back of the stage. There is a spot light illuminating the front of the stage. I use different layering and resolutions to articulate space in my paintings. The queens on the boxes are a higher resolution and printed as a photographic image using CMYK whereas the back of the stage is a much lower resolution with hand painted colors underneath. These different layers create a visual dynamic where the viewer sees the works in different times. If you photograph the work it will render the two grounds closer together but if you are standing up close and in person the painting has very different parts. These tricks make the illusionary components of the work work.

Greg Ito

Interviewed by Jennifer King

Your recent body of work references your grandparents' incarceration at the Gila River camp in Arizona during World War II. Can you tell me about your grandparents, and their role in your life as a fourth-generation Japanese-American?

My grandparents were the nucleus of our family when they were still alive during my childhood. I would spend so much time at their home (in Crenshaw, then they moved to Culver City) growing up because they would babysit my brother and I when we were little. I never knew anything about their camp experience until I was in first grade when my teacher Mrs. Ikegami invited my grandmother to our class to speak about the incarceration camps. It was one of the first times I felt so proud of my grandparents and what they went through and overcame, and the first time I really felt proud to be Japanese American. I even made a little model of an internment camp with little playdough people in it. I don't think I fully understood what happened and what the Japanese American community went through, but it was important for my family to share this history with my brother and I at a young age. Reflecting back on those years stirs up a lot of complex emotions. I remember it was the first time I learned the terms "jap" and "nip." Kids on the playground used to do the "Chinese, Japanese, Indian Chief" song pulling their eyes back so they would be squinted, and I remember my first fight was because a kid called me a "chink." But after that day my grandmother shared her story, we never talked about it again. Both of my grandparents seemed to have buried their emotions deep down inside, keeping a lot of their experiences to themselves. I think they were just happy living in the present with their family and being the best grandparents they could be without dwelling on the past. A lot of the older generations that went to the camps don't like to talk about their experience, and with so many first- and second-generation Japanese Americans passing away now their stories are fading away with them.

I think artistically my grandparents were a huge influence. My grandfather used to paint signs in his makeshift shop in Crenshaw. I used to see gallons of paint in his little workshop in his backyard and the posters he would paint for family events like my birthdays, and signs for booths at our Japanese community centers obon festival. I think this is why I gravitate to using house paint in my paintings. He also tinkered in his workshop making weird funny sculptures and objects. He was also a cartoonist, and was asked to bring his portfolio to Disney studios but turned down an offer after learning the pay was lower than the white animators. We have some carvings he made during his time in camp that were small gifts for my grandmother. They are some of the most beautiful objects I've ever seen. The carvings are delicate and small renderings of deer and rabbits from Bambi, which was released during the time they were in camp, and intricate inlay work that spelled my grandmother's name Sue, which was short for Sueko. He smoked cigarettes and watched golf all day in his old age and I thought he was so cool.

My grandmother was a seamstress for her own pleasure. She always had a dedicated sewing room in their home, full of machines and clothing she would make for herself. I loved flipping through the patterns and different fabrics she used. We were never allowed to go in the room without shoes because there would be pins stuck in the carpet that would be accidentally dropped while she was working. My brother and I would crawl slowly on the ground looking for needles for her, collecting them on these small Japanese pin cushions. She would tailor our clothes growing up, and her craft lives on in my mom and aunty who are now the family seamstresses. My grandmother was very old school, and I admired her dedication to her craft and passing down the knowledge to her daughters. I think between my grandmother's sewing room and my grandfather's workshops, these were the first "artist studios" I ever encountered.

There's a recurring image vocabulary that appears across many of your paintings. Can you walk me through some of the forms that appear in What Will Remain?

My visual language has been developing over the years using a lexicon of images and symbols that I imbue with my own meanings. In What Will Remain I painted a house, simple in its form, to its basic elements so it operates more as a symbol of home, shelter, safety, and family. A red door is open, which can be both welcoming or a sign that someone left in a hurry. What looks like an ocean is actually a cityscape of twinkling lights representing a larger ecosystem of cultures and communities that we exist within. The sunset clouds are representative of transition. The red sun is a nod toward my Japanese ancestry and a symbol of the passing of time. The poppies are a reflection of my family's lineage of being from California, Los Angeles specifically, and the cycles in life that are mimicked in the seasons. The window frames are from a western origin, simple four-pane windows that operate as portals looking into my world. The flames have multiple meanings one being destruction and loss, and the other as change and renewal. Influenced by California's wildfires, I'm inspired by people who have lost their homes and decide to rebuild on the same land, much like the Japanese American community who lost their homes and businesses in California, but decided to move back after their incarceration to rebuild. Lastly the ginkgo tree is a nod to "family tree." Ginkgo trees are also rooted in Japanese spiritualism and are a medicinal treatment for memory loss. The leaves on the tree are memories, which fade and fall, returning to the earth much like the stories and memories that are lost when older generations pass on.

Given the importance of family narratives in your work, how has becoming a father impacted your art practice?

Becoming a father has changed the family narratives in my work so much. As much as I reflect on the past, having my daughter Spring in my life keeps me looking toward the future. I keep asking myself, with the histories I unpack, what do I want it to inspire within the viewer? While my work is personally inspired by my family's history, it is not necessarily about the internment camps. I want my work to be accessible to all communities because almost every culture has gone through a traumatic experience like the Japanese American camps at some point in history. We all deal with loss, tragedy, trauma, and hate; with that, how do we as people persevere and overcome? From a personal standpoint my work helped navigate me through the pandemic when my partner, Karen [Galloway], was pregnant during the lockdown. I couldn't believe I was bringing a life into such a broken world filled with hate and fear. But looking back at my grandparents' history of being in the camps, falling love there, and leaving to start again and build their family kept me going, and it became ever more present in my practice. I think right now I'm at the turning point in my work as I look to the future for inspiration vs the past and I can thank Spring for this new chapter in my work.

April Bey

Interviewed by Jennifer King

For readers of Unframed who aren't familiar with your work, what would you like them to know about Atlantica and its relationship to your art practice?

Atlantica is my home planet. I make work from the perspective of being an alien from another planet assigned to Earth as an observer and reporter of humanity. This was a story my science fiction Blerd father told me to explain why we both looked differently than the majority. Much like an alien sent to explore, in my own practice I mix complicated processes and materials together to see what happens and discover the building blocks of what makes up the whole. I try to understand what makes up humanity and the ills still prevalent through forms of colonialism and supremacy and, as an Atlantican, reinterpret to form large and beautiful visual alternatives. I show speculative Black futures as only an alien entity observing can imagine. I work in textiles often due to the repeated and built up nature of its construction—I like seeing the components of complex problems and imagining the removal of what isn’t working while fertilizing what is.

Oui Outside, the piece LACMA just acquired, is a digitally woven blanket with hand-sewn elements. At first glance, the imagery evokes lush plant life, dense with leaves and flowers. On closer inspection, however, one discovers fingers and hands with highly decorated nails are an integral part of the composition. Can you tell me more about this work?

Oui Outside depicts the indigious plant life on Atlantica that is mostly tropical, high-humidity plants with flowers that are a Black woman's hands adorned with long custom acrylic nails. The piece is also about Black opulence and pleasure—the pampering that goes into getting your nails done and having them admired. I use the Black woman's hand with acrylic nails as the flower—the object of our affection. On Earth acrylic nails in some settings can be villainized as "ghetto" when on the Black body but "stylish" or "trendy" on another more privileged body. The symbolic image of a Black woman's adorned hand born from pampering and luxuriating is the only understanding of this image we have as Atlanticans—it grows everywhere on the planet.

What are you working on now in your studio?

Right now I'm working on works for my show titled I Believe in Why I'm Here opening this fall, September 1, at Simon Lee Gallery London.* It's focusing on Atlantican expressions of love and in particular self-love as a major planet-powering element required of all inhabitants. I'm working on more scenes from my home planet as well as textile representations of key self-care figures from my planet that are also stationed on Earth.

*This conversation took place in August 2022.

Kyungmi Shin

Interviewed by Jennifer King

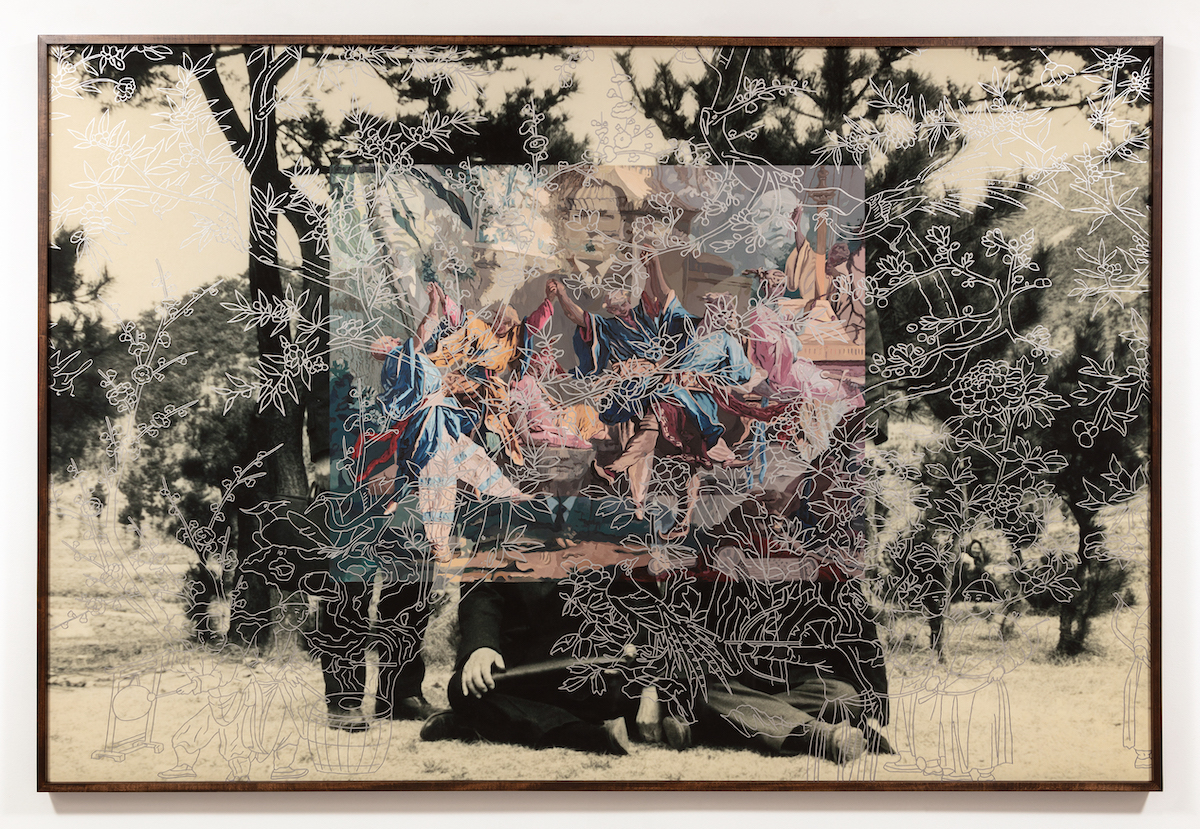

Your work speaks to historical perceptions of Asia in Western culture, drawing from sources ranging from Rococo paintings to Chinoiserie wallpaper patterns. Can you talk about the historical imagery and motifs you incorporated in mirrors of hard distorting glass?

The European image I reference in this work is La Danse chinoise, from 1748–50, a Beauvais tapestry work based on a painting by Francois Boucher, the Rococo painter who was also the court painter to Louis XV. When I encountered this image, I was struck by how the Chinese characters are depicted as if they are putting on a play, perhaps a comedy, for the audience, like court jesters. The section I am using for my work shows four Chinese men dancing with abandon. Chinoiserie depicts the far east and people in scenes that exoticize and sometimes infantilize the characters. In the later Rococo period, these characters are replaced by monkeys in Chinoiserie landscapes.

I am juxtaposing this over a photograph of Korean men presented in a formal portrait in a pine forest in 1960s Korea. In real life, they are stiff, some of them seated on the grass cross-legged as elders would be in a formal sitting. Their formal body language shaped by the Confucius decorum contrasts with the Chinoiserie painting of frolicking Asian men.

What led you to start working with family photographs?

I started to investigate the photographs in my family photo archive about five years ago when my father’s Alzheimer symptoms were getting worse. I felt an urgency to capture narratives from his life. As I spent more time looking at these old photos, I realized that these photos were not just personal records but also a snapshot of an era, a region, and thus function as historical records. I started to use these photos as a starting point to create conversations about the relationship between cultures, perceptions, hybridity, and creolization that happens as a result of trade, immigration, and colonization.

Tell me about the title of your exhibition last year at Various Small Fires, citizen, not barbarian.

I wanted to use this quote from Edouard Glissant to express the necessity to claim our need to belong. My works in the exhibit explored the complexities of many cultures, religions, and practices that we embody as immigrants and transplants, and this quote, “citizen not barbarian,” seemed to address the essence of the struggle as a person of color living in the West.

I am going to quote jill moniz from the press release she wrote for the show as she explains the quote powerfully. “Citizen not barbarian'' is a quote from Edouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation where he describes the otherness and its internal and external positionality beyond how it’s understood through a Western lens that orders and sustains systematic hierarchies. Glissant focuses on opacity—a lack of transparency for and toward the other—that can “coexist and converge, weaving fabrics. To understand these truly one must focus on the texture of the weave and not on the nature of its components,” looking at the “Other” as a citizen and not a barbarian.

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.