Happy Pride Month! As June comes to a close, we’re sharing highlights from our exhibitions and collections, selected by LACMA staff members to commemorate the month and celebrate queer culture. The museum’s encyclopedic collection contains numerous stories from the LGBTQ+ past—some hidden, and some out and proud—and the pieces below, and the accompanying reflections, offer unique perspectives on queer identity and history and their crucial connections to art and culture.

Rosanne Kleinerman, Teaching Artist

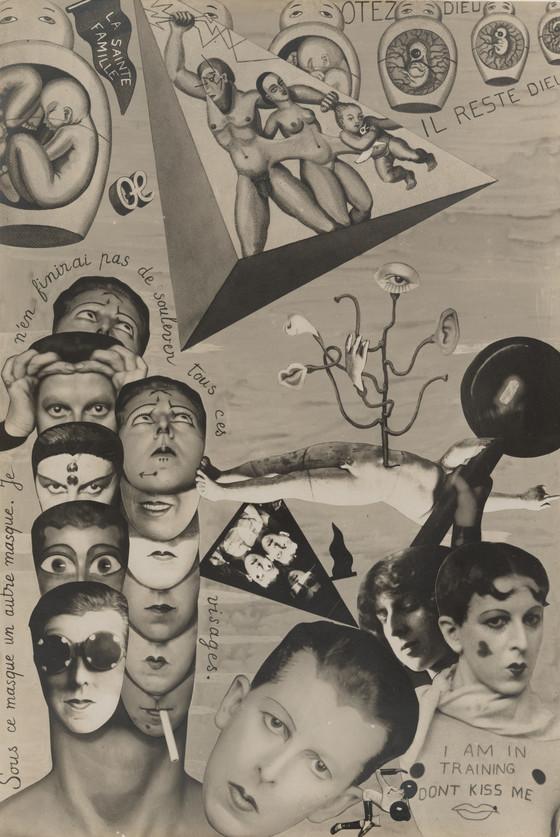

Claude Cahun, I.O.U. (Self-Pride) (1929–30)

I.O.U. (Self-Pride) is the title of an extraordinary photograph in LACMA’s permanent collection, by the artist Claude Cahun (or is it?).

Hand-written along the lower left side of the photo (English translation): Under this mask, another mask. I will never finish lifting up all these faces.

Here’s a story of two artists who lived out and out loud while masquerading in public. Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe were childhood friends in France. Schwob was a writer, photographer, and sculptor, Malherb, an illustrator, designer, and photographer. They were artistic collaborators, life partners, and later step-siblings when Schwob’s father married Malherb’s mother. Around 1914 they each chose alliterative gender-neutral names. Lucy Schwob became Claude Cahun. Suzanne Malherbe became Marcel Moore.

Cahun’s self-portraits, often in male drag, were actually collaborations with Moore. The photos, forgotten or hidden, were never exhibited in Cahun’s lifetime.

In 1937, the artist couple moved from Paris to the island of Jersey, to escape the Nazis. But the German troops invaded the island, so they created anti-Nazi propaganda pamphlets promoting mutiny, that they distributed to German soldiers under the pseudonym “The Soldier With No Name”. Who. Does. That?!

When they were found out, they were imprisoned and sentenced to death. Their lives were spared when the island was liberated. (Thanks, Dad!)

Life wasn’t a cabaret after the war. Their stories end sadly. But today, while looking at their art, we can celebrate the bold and daring lives of two brave artists that lived out loud and under cover.

Grant Breding, Associate VP of Retail & Merchandising

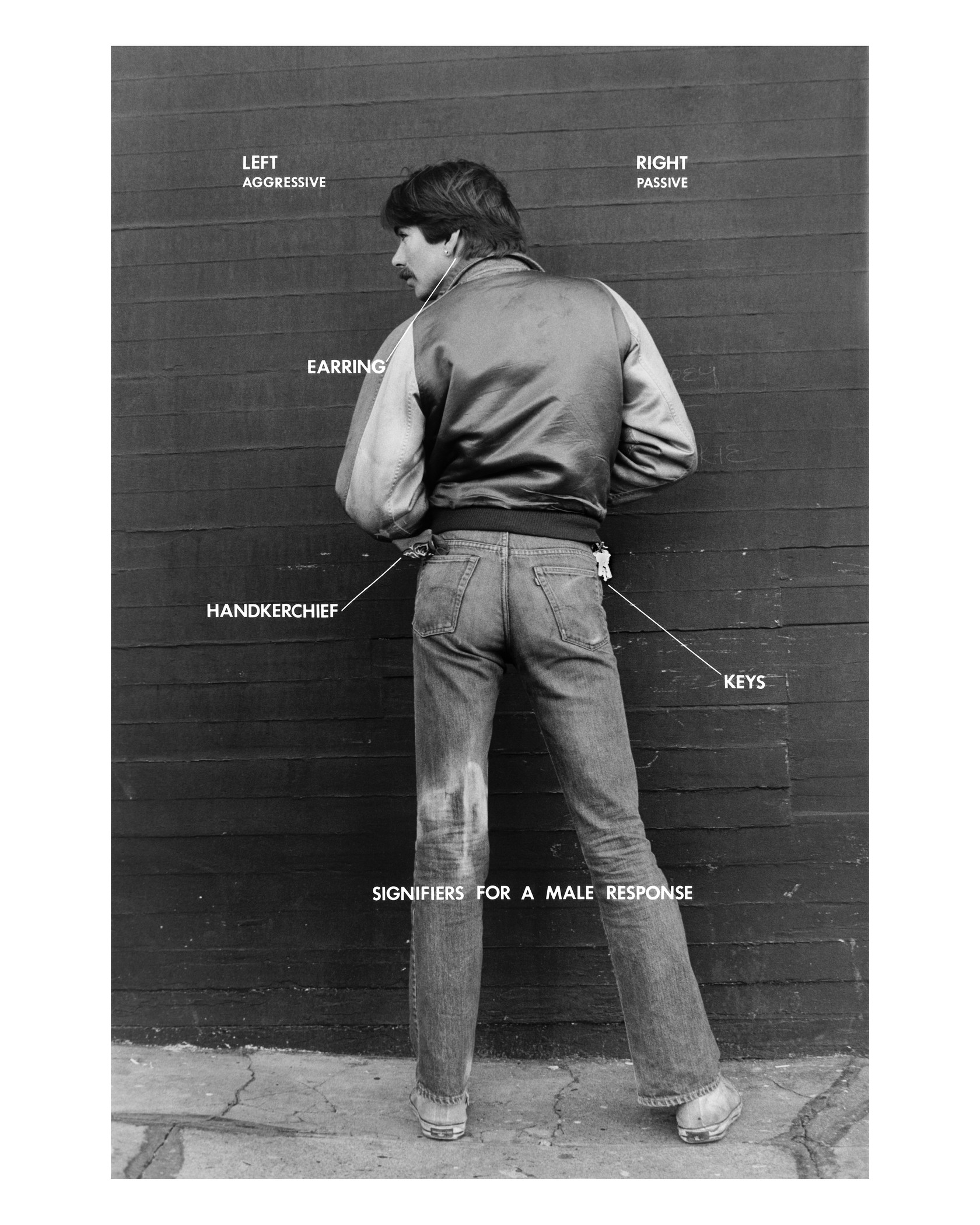

Hal Fischer, Signifiers for a Male Response (1971, printed 2014)

There was never a closet for me to come out of. I was never in one.

I twirled the batons for show and tell in the first grade and never looked back. Additionally, I have never needed to inform anyone that I am gay since my flame shines brightly from a mile away.

Yet I find the subtle signifiers gay men used in the 1970s pre-AIDS glory days charming, resourceful, and a reminder of a different time when codes, signs, and symbols were how you told those that knew them who you were.

By choice or necessity, many gay men were not out publicly, and being openly gay wasn't always easy, but the need to connect was strong. Wearing a specific-colored handkerchief from the full spectrum of the rainbow in either back pocket could tell those who knew the secret codes what you were. Branding and marketing all in a single hanky.

If you know, you know—hi, Mary!

Hal Fisher's Gay Semiotics: A Photographic Study of Visual Coding Among Homosexual Men is considered one of the most important works in queer history. His documentation is flawless. Elegant and direct. The piece Signifiers for a Male Response represents the times perfectly and details the simple but effective codes created to be both visible and invisible in public spaces.

I am grateful this is a part of LACMA’s permanent collection.

Holly M. Crawford, Director of Adult Public Programs

Frida Kahlo, Weeping Coconuts (Cocos gimientes) (1951)

This work is currently on view in the Modern Art Galleries.

I first saw Frida Kahlo’s artwork in Spanish class in high school. I was drawn to her use of color and felt a strong connection that I could not understand. Speaking to other artists and friends, I know this is not just a queer experience and it demonstrates that her work speaks to people in very intimate ways.

I think it was Frida’s paintings where I first saw disability, pain, queerness, and heartbreak translated into a visual form profoundly. As a young art student, I tried to be as bold as her, sharing truths about myself that I couldn’t yet vocalize. Her work helped me see myself. I honored her by tattooing one of her self-portraits on my shoulder in my twenties.

I didn’t anticipate that my admiration for her work would transform into a queer love affair that transcends time and place. Queer time, like queer love, is a non-linear and rebellious thing. When I visit the gallery to see Weeping Coconuts (Cocos gimientes)—a painting she produced toward the end of her life as her health drastically deteriorated—I feel like we are seeing one another: our bodies, our pain, our grief, a desire to feel peace and relief. I believe her work has helped many people see themselves and feel seen.

Her work reminds me that queer narratives are always relevant and that it’s important to challenge the ideas of who we are as queer people. And to honor the most vulnerable and tender parts of ourselves always.

Alicia Vogl Saenz, Manager, Family Programs

Agnes Pelton, Winter (1931)

When I first saw the painting Winter by Agnes Pelton in the recent exhibition Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group, 1938–1945, I was immediately curious about the pigeon in the left-hand bottom corner. The pigeon stands next to a dove on a large rock and seems to be looking out at the fantastical sky painted in shades of pink and blue. The dove is facing the other way, pecking the ground.

Pigeons are amongst the most despised birds and called all sorts of names. Yet, if you look at them closely, they are beautiful. Most pigeons are gray and black with stunning iridescent purple and green neck feathers. They are also amongst the fastest and strongest flyers, sustaining 60 miles per hour over hundreds of miles, which is why they are excellent messengers. They have amazing eyesight and were used by the coast guard to spot lost people at sea. Pigeons are indigenous to Eurasia and were domesticated about 5,000 years ago. They show up in Mesopotamian cuneiform tables and Egyptian hieroglyphics.

All of that is fabulous and fierce. However what strikes me the most and reminds me of my queer community is that pigeons can always find their way home. No matter what scientists do to confuse them, like being blindfolded and released at great distances they make it home. Pigeons use both earth’s magnetic field and the position of the sun to find their way. We members of the LGBTQI+ community make home with each other, even during the worst of times when we are driven underground by prejudice and laws. We spot a gesture or drop a code. Just like pigeons, we queers are resilient, have been around forever, are gorgeously feathered, and can often find our way home in the most unexpected ways.

John Rice, Director of Marketing

Michael Heizer, Levitated Mass (2012)

This work is currently on view outdoors on LACMA’s campus.

Walt Whitman's Earth, My Likeness starts strong as he contemplates the terrestrial. Deep within the earth he imagines fierce things capable of bursting forth. He sees the same within himself. And within the athlete of his current affections. (Where is this poem going?) Then he stops short, ending coyly with, "I dare not tell it in words." I'll be less coy and just get to my point. Levitated Mass is so gay. When I contemplate that particular piece of earth, I too find my likeness. What better representation of the lived queer experience? Taken out of context, transported by parade, laid bare—fierceness still within—and forever braced for anyone's passing comment. Who does she think she is?

Alexander Schneider, Assistant Editor

David Hockney, Mulholland Drive: The Road to the Studio (1980)

This work is currently on view in the Modern Art Galleries.

David Hockney moved to Los Angeles in 1964, and though he painted it almost two decades later, there’s no image quite like Mulholland Drive to give us an idea of just what a playground of possibilities Los Angeles must have seemed like to the gay twenty-something leaving behind the gray skies—and by his own accounts stifling social atmosphere—of England. He dove headlong into the gay scene of '60s California, painting nude men and his friends and lovers going about their lives, especially as they lounged in and around sun-drenched swimming pools, helping to establish an irresistible image of life in California that continues to attract newcomers, queer or not, to this day.

Though the isolated geometry of some of his most iconic Los Angeles works like A Bigger Splash seem downright frigid, the kaleidoscopic geography and colors of Mulholland Drive are pure joy. Painted by Hockney while back in England from memory (though the phrase “from memory” does seem too much concerned with accuracy for this hyper-real chaos), it communicates the allure that far-flung places seem to hold for so many queer people. As a newcomer to Los Angeles myself, who moved here directly from Hockney’s all-too-gray home country, sitting in front of this panoramic canvas captures how I still feel about this city on certain days.