The story of an artwork does not end after its completion; it changes owners, appears in short- or long-term exhibitions, and may undergo treatments, all of which contribute—in one way or another—to the way we make sense of it from today’s point of view. A work’s list of known owners, “provenance” in museum-speak, is inextricably bound with the history of us humans, from the broadest strokes to micro-narratives. The civic mandate of public institutions like LACMA includes making sure—to the best of our ability—its vast encyclopedic collection was acquired through a series of lawful and consensual transactions, ideally traceable all the way back to the maker(s).

Naturally, this is a Sisyphean task, not just due to limited resources like time and funds to sustain provenance research, but also because only a fraction of the objects we consider “art” today are continuously accounted for in the annals of history. It may seem like modern art specialists have it easier, since the time span we deal with is much shorter and the means of documentation more diverse, but this period also coincides with the unprecedented democratization and politicization of new art, as well as some of the most horrific tragedies in human history.

The Nazi vilification (and subsequent confiscation and re-selling) of avant-garde art as “degenerate” is a historical phenomenon to reckon with—and LACMA is home to a substantial collection of European modernism. Between 1933 and 1945 Jewish collectors in Germany and occupied Europe saw their property either confiscated or sold under duress during their flight from the Holocaust.

Sadly, such behavior was not limited to the Nazis. One could in fact argue that provenance research is of global relevance, since horrendous events in human history extend beyond the Third Reich to all corners of the world, from the Benin bronzes looted by the British in the 19th century to the more recent trafficking of Near Eastern antiquities as a tool for financing terrorist groups. A number of governments and institutions have launched repatriation initiatives, while others had to return artworks to the countries of origin or the descendants of victims as a result of successful lawsuits, but all of the above involve very long, costly processes.

On a brighter note, provenance research can become a portal for (re-)encountering remarkable personalities, diasporic care, and solidarity across unexpected lines—all testaments to how art has given shape to lives and brought them together, mostly outside of art history textbooks. This was the case when we received an unexpected treasure in the form of an email from the Comité Chagall (the association in charge of Marc Chagall’s estate) in response to a query about LACMA’s painting by Chagall, Violinist on a Bench (1922).

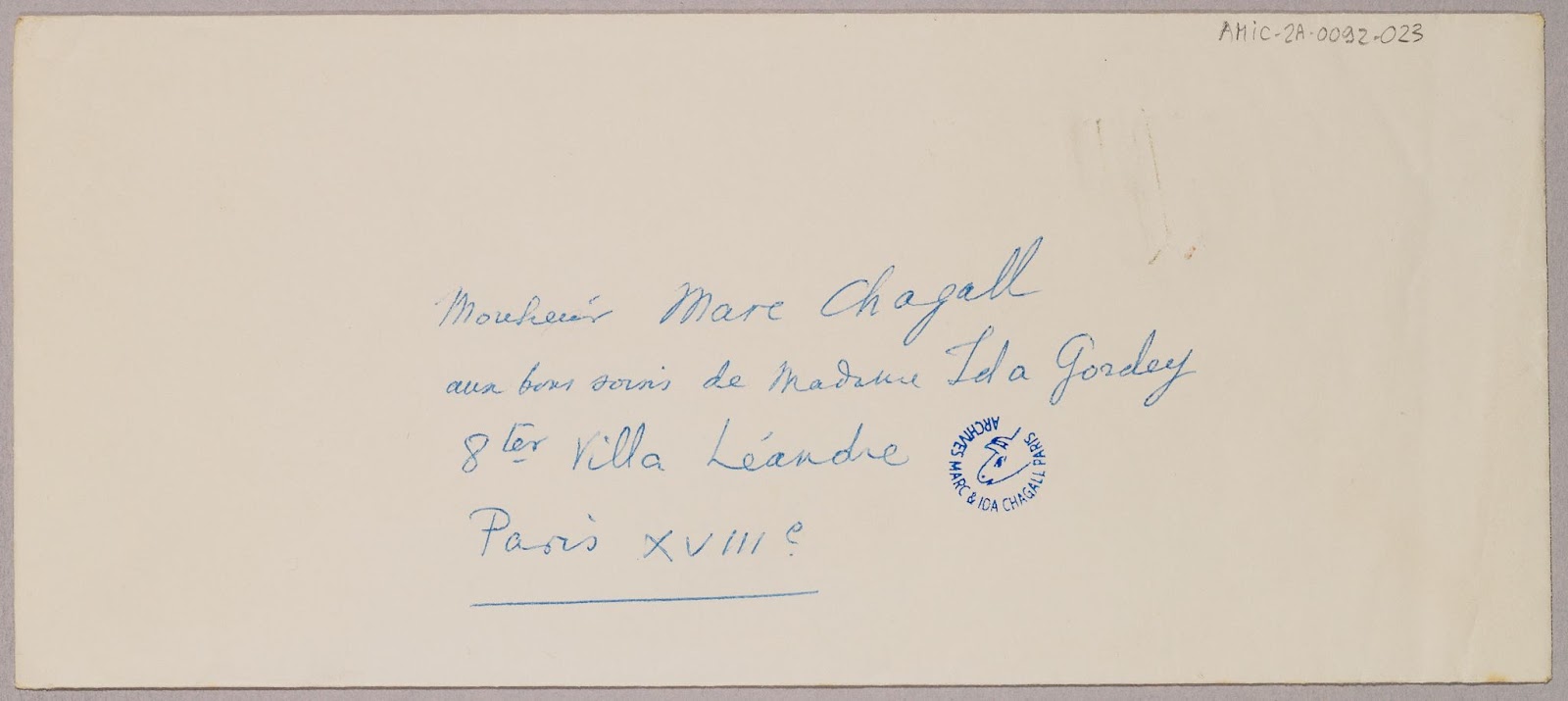

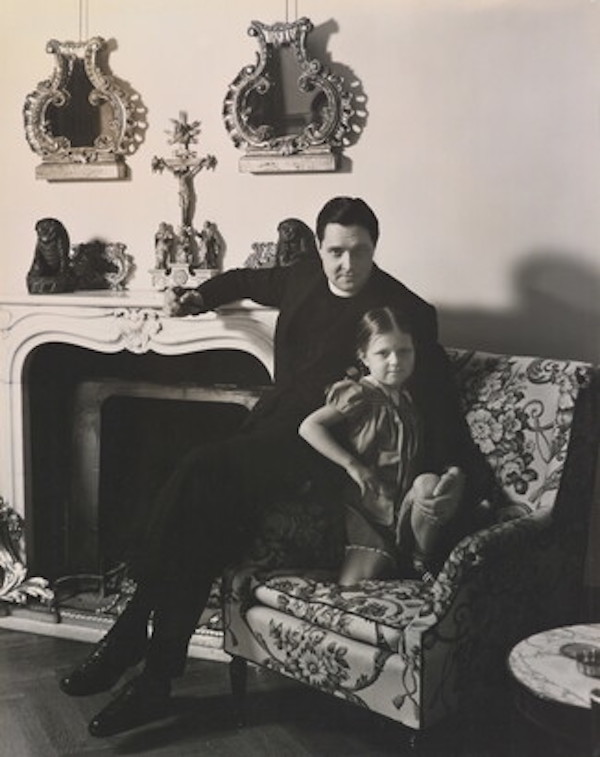

Among the documents they sent were scanned copies of two 1948 letters from Reverend James McLane—the husband of Mrs. Mary Day McLane, who would donate Violinist on a Bench to LACMA in 1964. The earlier letter begins with the words “Dear Marc Chagall” just underneath the St. Matthias letterhead listing McLane as its rector, and—without any forced epistolary niceties—quickly turns into a heartfelt expression of admiration and wonder:

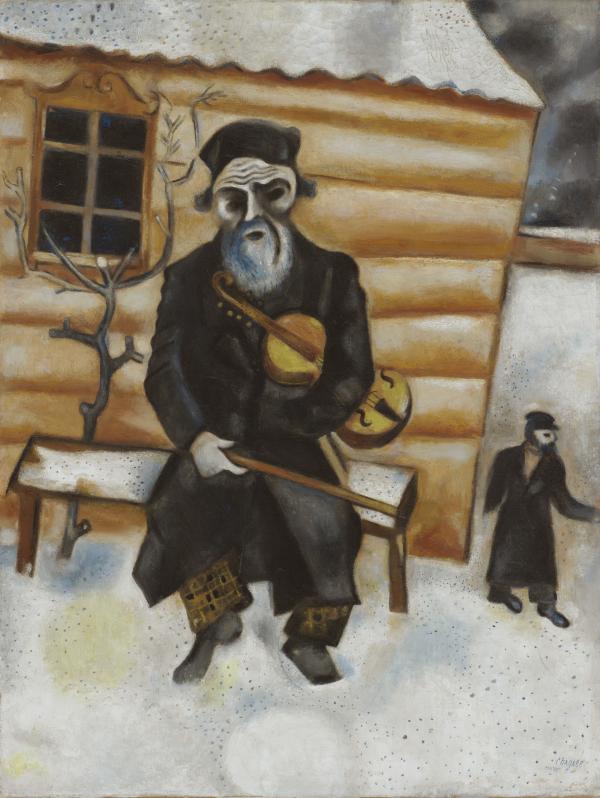

“Thank you for your new letter telling me about my new Chagall. It is a very beautiful and moving picture—very frightening, really, in its sense of cold & loneliness & remoteness—primitive—and Russian. Only you can paint snow with such magic and tenderness. I feel in this picture you have painted again (as if in Paris in 1922, you were saying “good-bye” to them) all the snows of your Russian childhood. He hangs, your old Jewish violinist, on the dining-room wall, just outside my bedroom. . . and every night I say good-night—and he bends forward out of his frame & bows to me—sombre, severe, with the dignity of an old Orthodox ikon [sic]!”¹

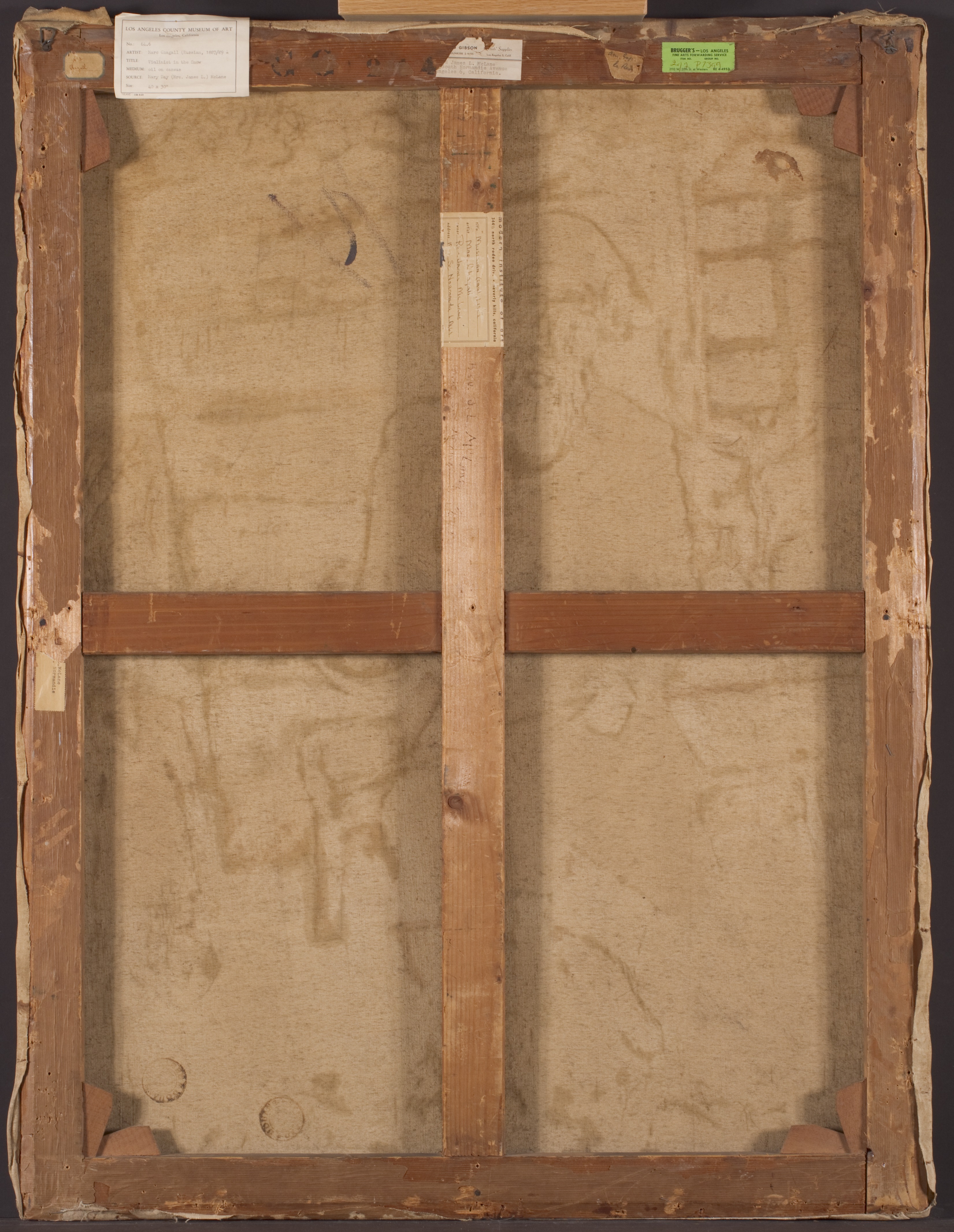

Rev. McLane was not only the rector of the Episcopalian St. Matthias Church in Los Angeles, but also once the chairman of the Los Angeles Chamber Symphony Society, as well as a noted collector involved in the city’s nascent art scene from the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum) to the short-lived Beverly Hills Modern Institute of Art.² On the occasion of an annual music festival organized by a patron group at the Pasadena Art Museum, the Los Angeles Times mentions a Chagall exhibition culled from the McLane collection, describing the reverend as “one of America’s prominent collectors of the artist’s prints and paintings."³ His letters to Chagall, which are currently held by the Marc and Ida Chagall Archives in Paris, constitute a rare and invaluable resource for provenance research, since Violinist on a Bench belongs to a peculiar group of works that Chagall made after moving to Paris in the early 1920s. On his way to the French capital, the artist had unsuccessfully attempted to recover a considerable number of his works left in Berlin for safekeeping on the eve of World War I, and once in Paris, he had to reckon with the disappearance of additional works from his pre-war studio there. Chagall decided to recreate some of these early paintings from memory, as well as others sold to Russian collections, which perhaps explains why our Violinist is not accounted for in the only published catalogue raisonné (from more than half a century ago) of Chagall’s paintings. The McLane letters effectively establish LACMA’s painting’s presence in L.A. in the late 1940s.

The contents of these letters also suggest how Violinist on a Bench might have made its way to Southern California, as it mentions a “Los Angeles dealer whose wife acquired this picture last summer from Holland through Jewish friends of theirs.” Out of a handful of Los Angeles dealers selling modern European art at the time, it is very likely that the painting came through Dalzell Hatfield, whose wife, Ruth Hatfield, was very involved in the family business. The Dalzell Hatfield Gallery records, at the Getty Research Institute, are as yet unprocessed, but we hope to find out for sure when the gallery archives are made available for research. For now the 1948 letters provide clues only.

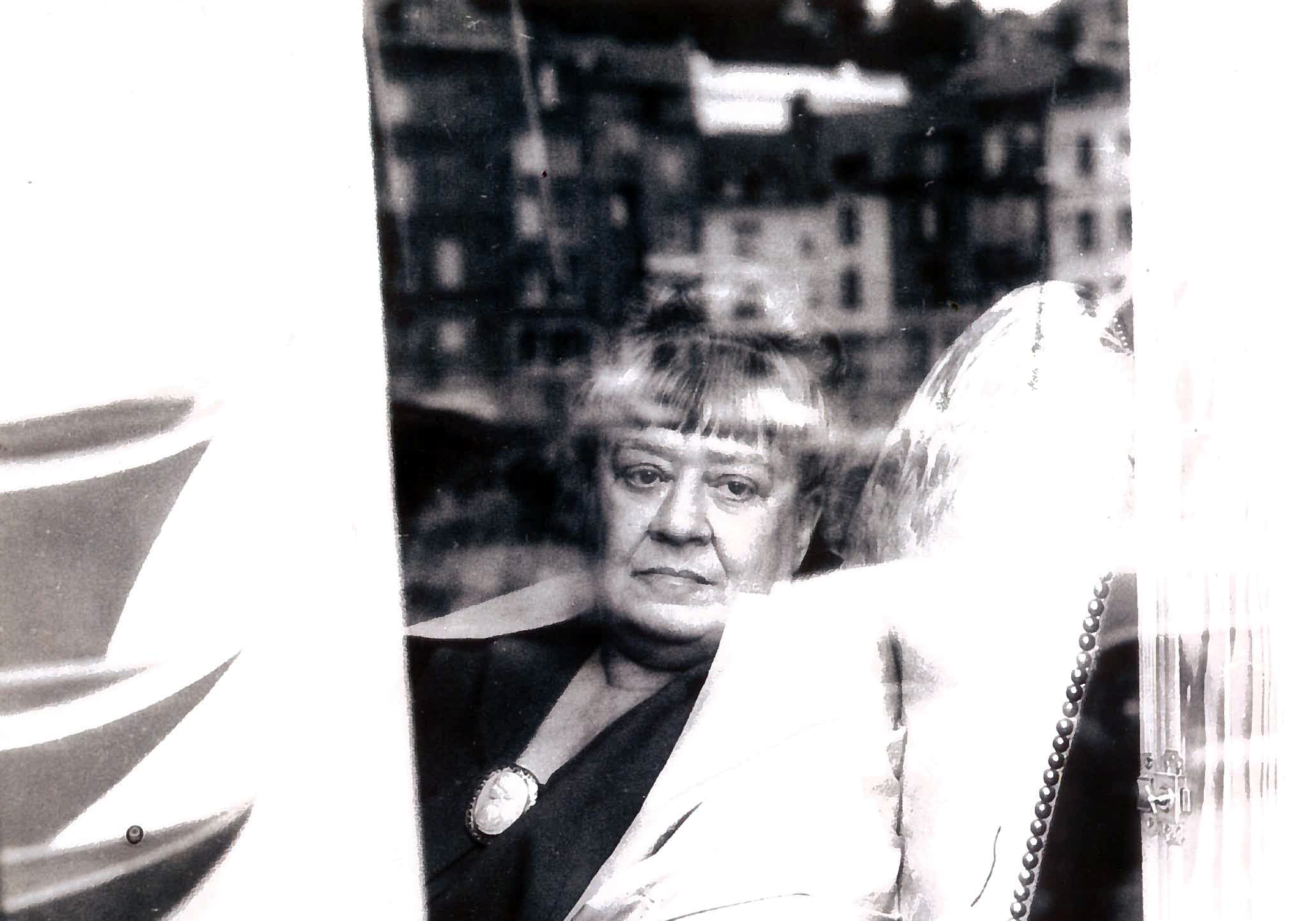

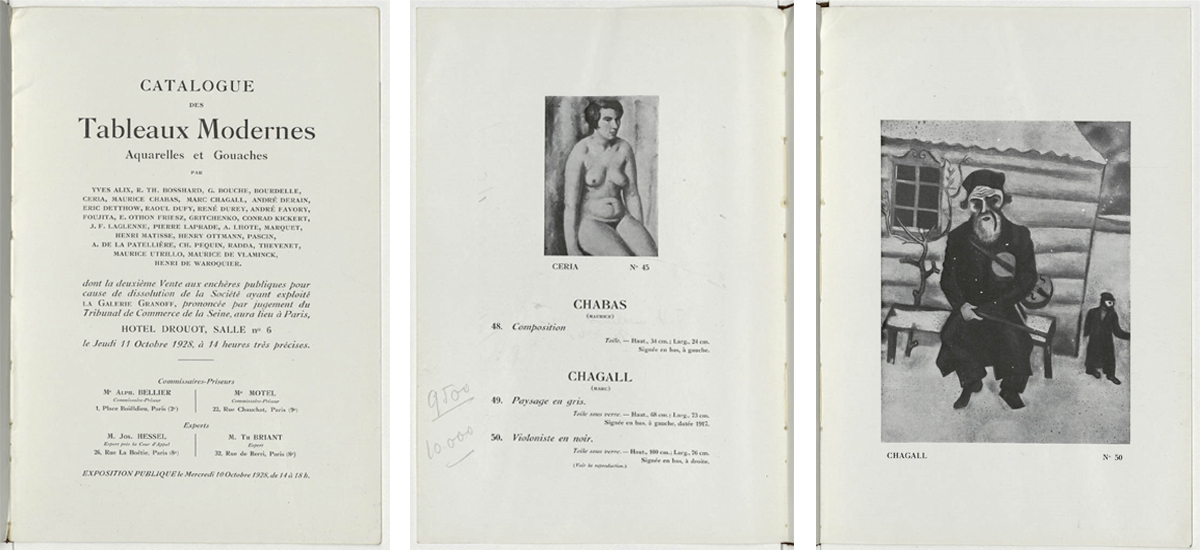

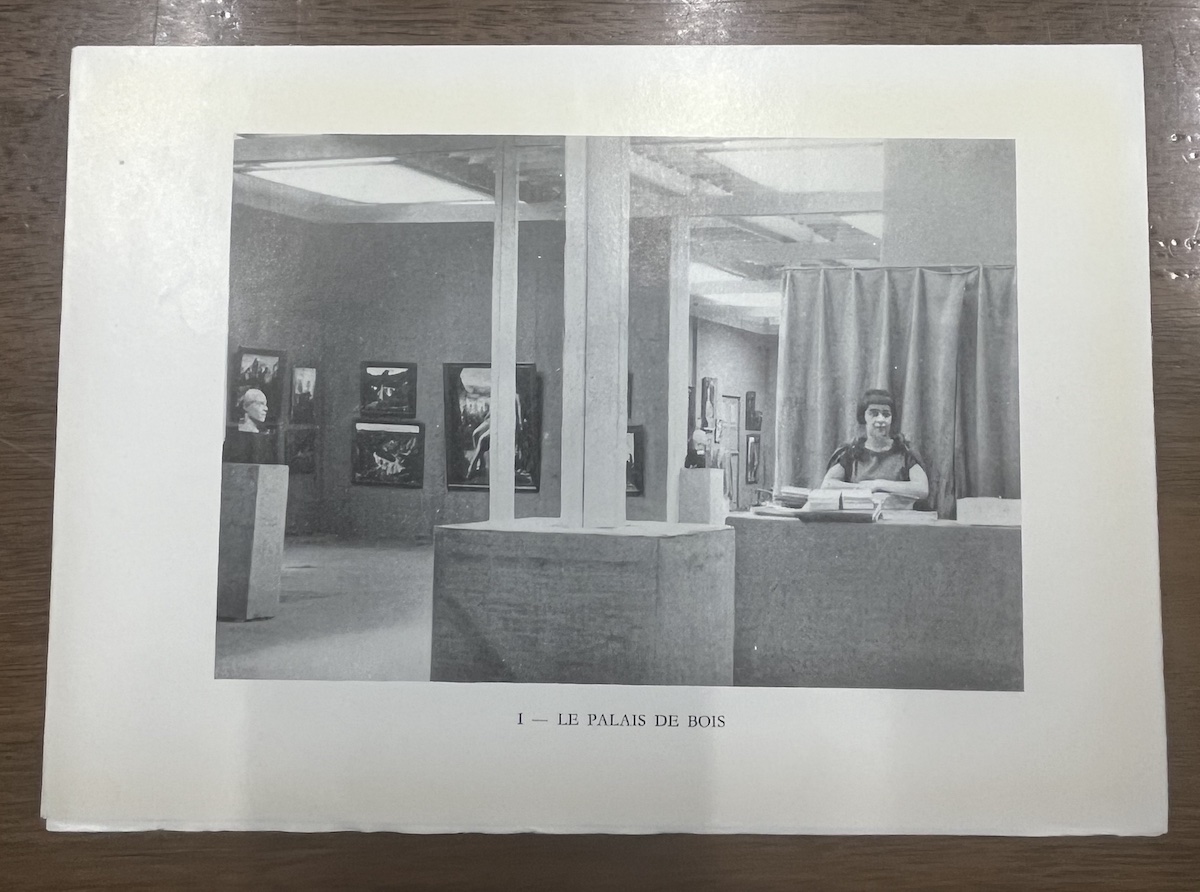

Another scanned document from the Comité Chagall registers the last known public appearance of LACMA’s Violinist on a Bench before World War II: it is the catalogue for an auction that took place on October 11, 1928, at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris—the second of four auctions that liquefied the assets of the recently shuttered Galerie Katia Granoff.⁴ Herself a Russian émigré like Chagall, Granoff was a pioneer in the male-dominated world of art galleries in Paris, and worked with Joan Miró, Claude Monet, Amédee Ozenfant, and Fahrelnissa Zeid, among others. Granoff met Chagall while working as a secretary at Salon des Tuileries in the early 1920s, shortly before starting her own business in 1924, and became his sole representative until 1928.⁵ Her first gallery, on the Boulevard Haussmann, had Auguste Perret-designed wood furnishings, which provided a sober, modern backdrop for the avant-garde works on display (unlike most other Parisian galleries at the time).⁶ Granoff ultimately had a long and successful career as an art dealer, in addition to her award-winning work as a translator and a poet.

Drouot used to (and to an extent, still does) have a more auctioneer-oriented, less centralized structure compared to Anglo-American auction giants like Sotheby’s and Christies, so there are currently no strong leads as to where Violinist on a Bench might have wound up after Galerie Katia Granoff. However, searching for clues in her writings, one may come across wry expressions of affection and solidarity for a hurting artist, with whom she had a lot in common. When she broaches the subject of anti-Semitic and xenophobic attacks on Chagall’s ceiling frescoes for the Opéra Garnier in her memoir, Chemin de ronde [“Round Path”], the dealer’s exhortations are simultaneously tinged with the deepest admiration and a touchingly profound understanding of what it means to be a “foreigner”—still, after several decades of residence—in one’s adopted country:

“Forget this wound, this ransom of the Opera ceiling, a gift to France. To my mind, it evokes the terrible aches [courbature] of Michelangelo. After having painted the ceiling of the Sistine [Chapel], he was not able to straighten up and could only stand with his head thrown back for a long time. That is the price, dear Marc, of a giant’s work.”⁷

Provenance research rarely gives us all the answers we are seeking to establish immaculate chains of custody, but it can also provide an opportunity to reveal or dust off stories such as those of Granoff and the McLanes and Chagall’s Violinist on a Bench in LACMA’s collection. Museums have often been compared to mausoleums, because time is thought to stop for those objects that withdraw from the world to be displayed under glass cases or at arm’s length. However, I would argue that the passion, devotion, and advocacy of previous owners still manage to enliven the works, putting a human face on things we are often taught to revere as transcendent and outside of time. They remind us humans that art too has a pulse of its own, and this heart beats through the lives it touches.

1. Reverend James McLane to Marc Chagall, February 10, 1948, AMIC-2A-0092-023, Archives Marc et Ida Chagall, Paris.

2. See, for instance, “Concert Will Honor Leader,” Los Angeles Times (September 20, 1950): B2.

3. Joan Burnham, “Pasadena Art Alliance Sets Date: Wine Fete Bubbling on Party Scene,” Los Angeles Times (May 5, 1957): D1.

4. Alph. Bellier and Motel, Catalogue des Tableaux Modernes, Aquarelles et Gouaches, par (…), dont la vente aux enchères publiques pour cause de la dissolution de la Société ayant exploité la GALERIE GRANOFF (...) (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, 1928), no. 50.

5. Katia Granoff, Mémoires: Chemin de ronde (Paris: Union Générale d’Éditions, 1976), 42.

6. Granoff, Ma vie et mes rencontres (Paris: Christian Bourgois Éditeurs, 1981), 88.

7. Granoff, Chemin de ronde, 42.