To mark Juneteenth, Unframed is publishing an excerpt of an essay by Dhyandra Lawson, Assistant Curator, Contemporary Art, the full version of which can be found in the catalogue for LACMA’s 2021–22 exhibition Black American Portraits.

We make portraits because people elude us. People move. People die. People enter our lives and leave them. Portraits encapsulate the mortal and moving body.

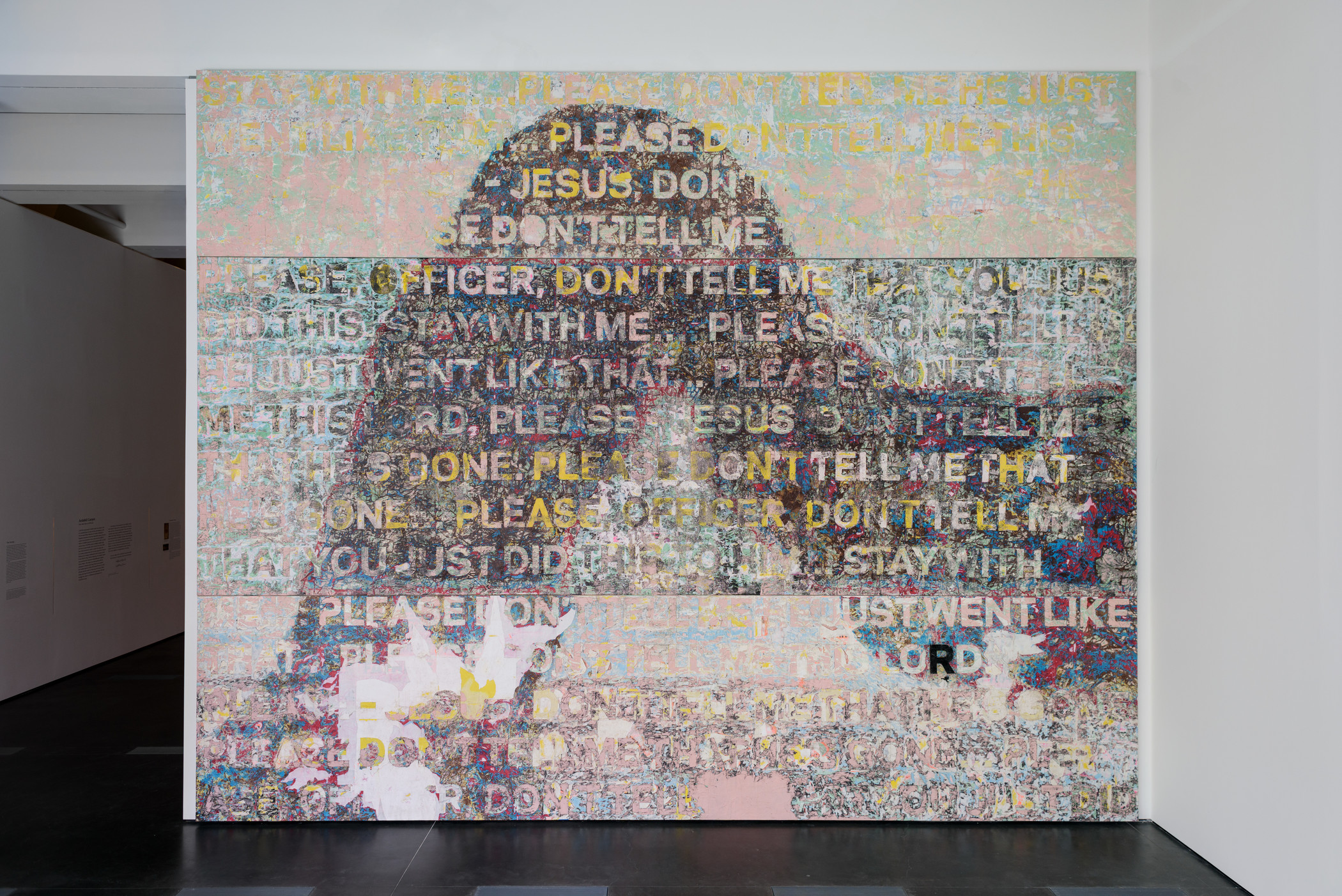

When visitors walk into the Resnick Pavilion at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the first artwork they see is 150 Portrait Tone by Mark Bradford. Layers of paper Bradford ripped and collaged culminate in a mural that reaches 20 feet high and spans 25 feet. The museum commissioned the work and presented it in 2017. It has been on view ever since—a permanent fixture in the Resnick Pavilion and a definitive work in the collection. The work frames every exhibition and human interaction around it.

“…Oh my God please don’t tell me he’s dead…”

“…Please Jesus don’t tell me that he’s gone...”

“…Please officer don’t tell me that you just did this…”

“…Stay with me…”

Bradford stenciled the transcript of Diamond Reynolds’s cries for her boyfriend, Philando Castile, across the mural. In 2016, Castile, 32, was driving with his girlfriend and her four-year-old daughter in Saint Paul, Minnesota, when police officer Jeronimo Yanez pulled him over. The officer told Castile he had stopped him for a broken taillight. Dashboard camera footage shows that Yanez pulled over Castile because he “look[ed] like people” that were involved in a local robbery. Yanez asked for Castile’s license and insurance. Castile said he had a firearm he was licensed to carry. Yanez replied, “Don’t reach for it then.” Castile assured him, “I’m not pulling it out.” Yanez fired seven shots through Castile’s car window, killing him. Yanez was charged with second-degree manslaughter and two counts of dangerous discharge of a firearm. On June 16, 2017, after five days of deliberation, a Minnesota jury acquitted him of all charges. LACMA presented 150 Portrait Tone four months later.

Bradford rarely shows the human form in his work.² Rather, he reveals traces of the body. From Philando Castile to the Africans who were sold on auction blocks, Black people have been distinctly visible in the Americas. Bradford’s choice is, as he has described, political.³

The artist uses urban debris. He collects posters and paper from around his South Los Angeles neighborhood. With water, glue, and a process of sanding, he builds up and tears the paper, then transforms the rigid layers into seamless compositions. Bradford’s laborious process implicates his body in his work. The papers the artist recovers from city streets are vestiges of the people who left them there.

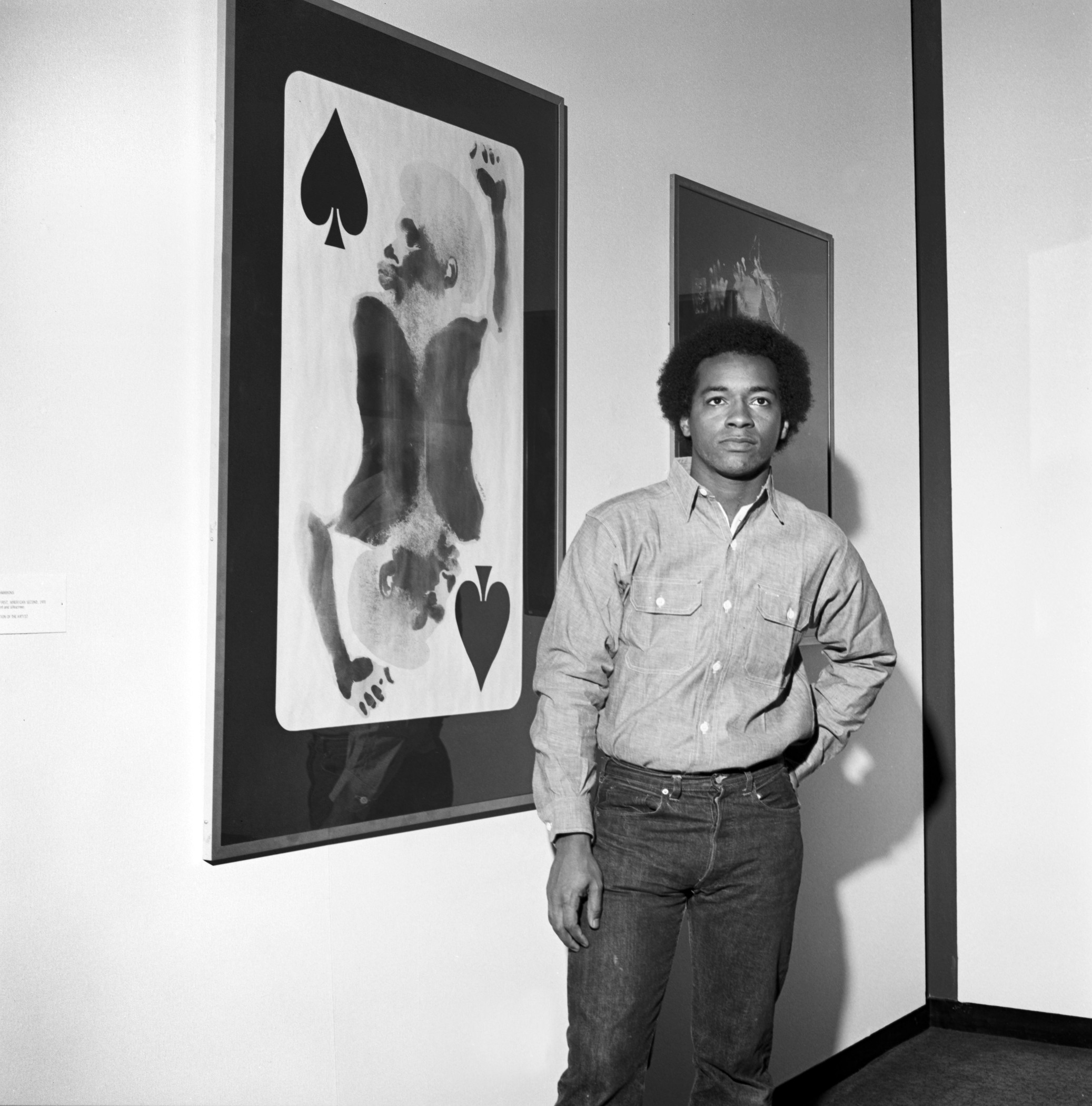

The physicality of Bradford’s practice recalls David Hammons’s Body Prints series. Hammons moved to Los Angeles in 1963 from Springfield, Illinois, to study art. He began making body impressions in 1968, just after he graduated from the Chouinard Art Institute (now the California Institute of the Arts). After that, he studied drawing with social realist artist and activist Charles White at Otis Art Institute.

For his Body Prints series, Hammons coated himself in margarine, Crisco, and baby oil. He then pressed his body onto paper and sprinkled the impression with charcoal or graphite to reveal a positive image. Some of his compositions depict figures socializing or involved in intimate exchanges. Other works express political commentary. Eventually, he applied his body prints onto other surfaces. The Door (Admissions Office) (1969), a glass door featuring two Black figures facing each other, alludes to segregation.

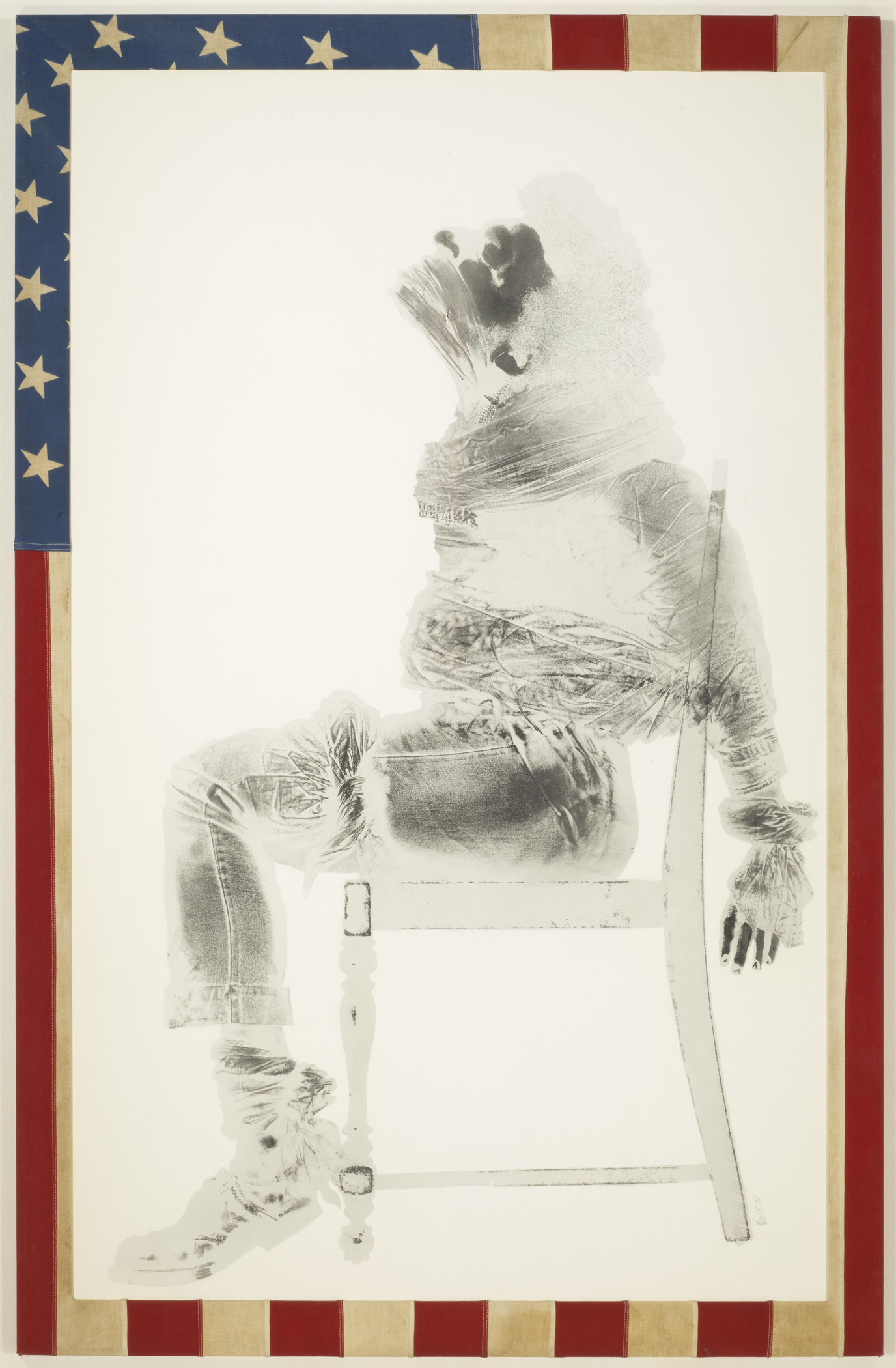

In Injustice Case, arguably the most famous print from the series, Hammons portrays a man gagged, chained, and lashed to a chair. The image references Black Panther Party leader Bobby Seale’s treatment during the trial of the Chicago Eight in 1969. The eight defendants were charged with having incited civil unrest at the Democratic National Convention the year before. During the trial, Seale, a co-defendant, repeatedly objected to not having legal representation. Judge Julius Hoffman ordered police to gag and bind Seale in the courtroom. Seale’s case was declared a mistrial and never retried.

Hammons impressed his body onto paper in the shape of bound Seale. He framed the image with an actual American flag; stars and stripes occupy the border of the work. The image amplifies a Black artist’s voice speaking out against his nation’s mistreatment of Black people.

Hammons was immersed in a community of Black artists and activists in Los Angeles in the 1960s. They established exhibition opportunities and support networks for Black Angelenos in churches, libraries, and civic centers.⁴ Black-owned galleries like Brockman Gallery dedicated their efforts to fostering the careers of artists of color; Injustice Case debuted there in April 1970.⁵ LACMA acquired the piece and presented it in Three Graphic Artists: Charles White, Timothy Washington, David Hammons the next year. The exhibition featured works by Charles White and then-emerging artists Hammons and Timothy Washington. The three artists were also members of LACMA’s Black Arts Council; founded by LACMA staff members Claude Booker and Cecil Fergerson in the wake of the Watts Rebellion, the group sought to promote the work of African American artists and engage more diverse audiences at the museum. Injustice Case is one of three works by Hammons in LACMA’s collection.

Scholars often compare Hammons’s Body Prints to X-rays. The contrast between black and white, and the indexical impressions Hammons makes, recall photographs. Unlike an X-ray, however, his monoprints emphasize the body’s exterior. In Injustice Case, Hammons’s jeans, hair, and fingernails have marked the paper. The print reveals the fibers of the rope around his knees and the bind yanking his neck back on his shoulders.

Hammons’s work accentuates the fundamental physical difference Europeans used to justify African peoples’ subjugation: their skin. The charcoal Hammons applies to paper materializes his Blackness. A slippage emerges between artist and subject—as Hammons takes on Seale’s physicality, he renders not only his social position but the social position of all Black Americans.

Bradford and Hammons do not simply simulate the likenesses of their subjects. The physicality of the artists’ processes reinforces the sensation of their subjects’ humanity. They implicate themselves, and the viewer, in their works. The physicality of Bradford’s process, and of Hammons’s skin, is on view. Bradford and Hammons grasp for a visceral sense of the elusive body—its utterance and its texture. They reinforce the humanity of Castile and Seale in situations where they were denied it.

1. “Dash Camera Shows Moment Philando Castile Is Shot,” New York Times, June 20, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/video/us/100000005176538/dash-camera-shows-momen....

2. Huey Copeland, “Painting After All: A Conversation with Mark Bradford,” Callaloo 37, no. 4 (2014): 817.

3. Copeland, “Painting After All,” 817

4. Connie Rogers Tilton, “Introduction,” in L.A. Object & David Hammons Body Prints, ed. Connie Rogers Tilton and Lindsay Charlwood (New York: Tilton Gallery, 2006), 16.

5. Kellie Jones, “In Motion: The Performative Impulse,” in South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 228.