Caitlin Spencer, Curatorial Assistant, Contemporary Art at LACMA, recently had the opportunity to speak to artist Tyler Hobbs about two works acquired by the museum and about the artist's engagement with generative art. Read their conversation below.

You can also read about work Hobbs recently created in dialogue with LACMA's permanent collection in this post as part of our series Remembrance of Things Future.

Tyler, in the past, you’ve mentioned studying computer science at The University of Texas in your early 20s and obtaining experience as a programmer. When and how did you start incorporating your knowledge of data science and creative abilities into creating generative art?

I was fortunate to receive a great education in computer science. That was a formative experience for me, and greatly shaped how I approached all work that followed. There are many components to computer science and programming, but one common thread is the need to analyze all problems and compose all solutions in a structured, systematic way. This provided me with a “procedural” view of the world. I began to view all objects in terms of the processes that formed them. And for every problem I saw, I wondered if a process could be designed to solve it. On the other hand, I have also been an active artist for my entire life. Drawing and painting have always been a passion of mine. For me, these were completely separate from programming and computer science for many years. It was only in 2014, at the age of 27, that I first began experimenting with ways to combine my passion for visual art with my professional skills as a programmer. Given how much programming had shaped my world, I knew it needed to become part of my artwork as well. I wasn’t aware of the broader world of generative or algorithmic art at that time. But, after a few different stumbling attempts to combine programming with visual art, I wondered if I could simply “write a program that creates a painting.”

The results of that immediately captivated me. I shifted my attention from drawing and painting towards generative art, and made several hundred generative works in the following few years. I began to find ways to take that procedural, systematic worldview I had developed from programming and apply it to visual art. In many ways, it helped me to abstract my aesthetic concerns—to get them out in the open and analyze them in a concrete way. At first, for the painter in me, this felt unusual and uncomfortable, as I was used to working intuitively. But, ultimately, it was to my benefit, and helped strengthen my aesthetic decision making process. In recent years, I’ve become interested in ways to combine generative and algorithmic methodologies with the physical media like paint that I have such a long history with. My work currently runs the gamut from purely digital art, to drawings, paintings, and other physical media, but always with a strong algorithmic component.

You have a section on your website dedicated to your generative art process, explaining how you sketch ideas, the repetitive cycle of programming, “adding bugs,” the mass output and curating process, translation from digital to physical, and so on. Thinking of systems of operations, how has generative art changed over the past 60-plus years?

Generative art has undergone growth and transformation in a number of ways over the decades since it began. I’ll do my best to quickly summarize why. First, there is the improvement in hardware. The first generative artists did not even have screens with which to view their work. They had to wait for a plotter (a mechanical drawing system) to draw the output in order to even have some idea of how it looked. And of course, these artists were working with huge, slow, expensive, and rare computers. There were very real limitations to what they could accomplish with those resources. Today, of course, we all have incredibly powerful computers by comparison (probably millions of times faster), as well as large, high-resolution screens and fast internet connections.

The second change is the improvement in software. The earliest artists had to work with primitive programming languages, which can be incredibly tedious and error-prone. There were no existing software libraries available to build from. Everything had to be dreamed up and written from scratch. Some of the programming problems involved in that can be quite difficult to solve. Today, generative artists benefit from decades of research and work into improved programming languages, operating systems, and graphics algorithms. Almost all of this knowledge is readily available as free and open-source software, making it accessible for all. There is even a wealth of software libraries designed specifically for generative artwork, such as Processing, created by Ben Fry and Casey Reas in 2001. All of that allows generative artists to be massively more productive. It only takes a little bit of code to do quite a lot!

Third, there has been an evolution in terms of who can make generative art. At the start, the only people who even had access to computers were scientists and engineers. So, it was rare for somebody with a background in, say, painting or photography to have access to algorithmic art as a potential medium. Additionally, algorithmic art really requires you to be able to program. Historically, programming has also been only narrowly accessible—most programmers were college-educated men. This is unfortunately still the case today, but at least the trends are headed in a more diverse direction. Women are programming in greater numbers, and the wealth of high-quality, free educational materials online allow anyone to teach themself to program at a professional level. As a result, there is a richer variety in backgrounds across the field of generative artists.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the art form itself has had time to grow and mature. The very first artists working with computers had nothing to build on. They had to imagine and create a new aesthetic out of thin air! Every artist that has followed has had the benefit of their example to learn from. This way of working can represent such a radical departure from our past, that in many ways, we are still artistically grappling with the implications and possibilities. What does it mean when your artistic tools can be hyper-precise, insanely fast, and never tire? How can your work change when you can design a system, integrate randomness into it, and then run it over and over to generate millions of images, for free? And how do we cope with the fact that, as complicated and powerful as a computer is, it’s almost impossible to get it to generate something with the quality, complexity, and surprising nature of a scribble drawn by a five year old with a crayon? Over the last decades, generative artists have pushed forward, exploring these questions and others. As a result, I find recent generative work to be richer, more nuanced, and more human than the work that preceded it. But, who knows how it might grow from here?

LACMA recently acquired Discrete Affection #3, a charcoal drawing, and Connected for the Moment I, a generative artwork minted as a non-fungible token (NFT). These two works were created together as part of a series you started in 2022, Mechanical Hand. Why title this series called Mechanical Hand? Can you talk about your interest in the difference between coding and natural observation, hand-made versus algorithm?

I chose the name “Mechanical Hand” for a couple of reasons. To start with, by working through algorithms, my own biological hands have become largely supplanted by computers and machines. They are an extension of my mind and body. The plotter has become the way that I often reach out and touch the physical world. Additionally, as you allude to, I am very interested in the innate aesthetic differences between the natural, analog world and the algorithmic, digital world. Computers are extremely biased towards producing clean lines, perfect shapes, and even fills. Everything is based around grids. The analog world is quite different: nothing is perfect, nothing is straight, nothing is even. Everything is rough and lumpy and fuzzy. I’m interested in visually exploring this difference through my work. Sometimes I do that by directly pitting the machine against the hand for the same drawing tasks. Other times, I use the machine where the hand would normally be expected, or I use the hand where a machine would be more appropriate. I also like to create work that uses both the hand and the machine, each one for something that it excels at. If you look at the trends for human civilization, it seems quite obvious that our lives are becoming more and more deeply mixed with machines and algorithms and programming. I think it’s important for art to look at that mixture of the biological and the mechanical, to see how they might coexist, and to see if they might arrive at somewhere richer and healthier than either could alone.

What is the inspiration or—thinking back to the breakdown of your process—the idea that sparked Discrete Affection #3 and Connected for the Moment I?

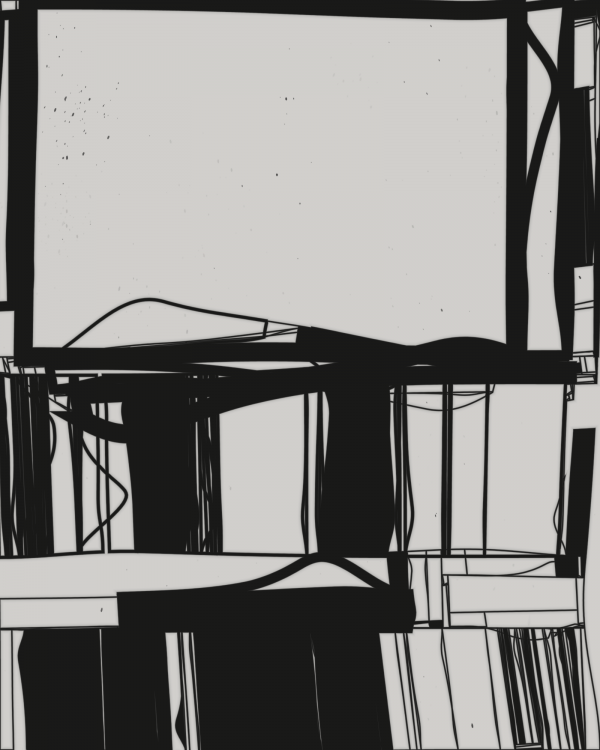

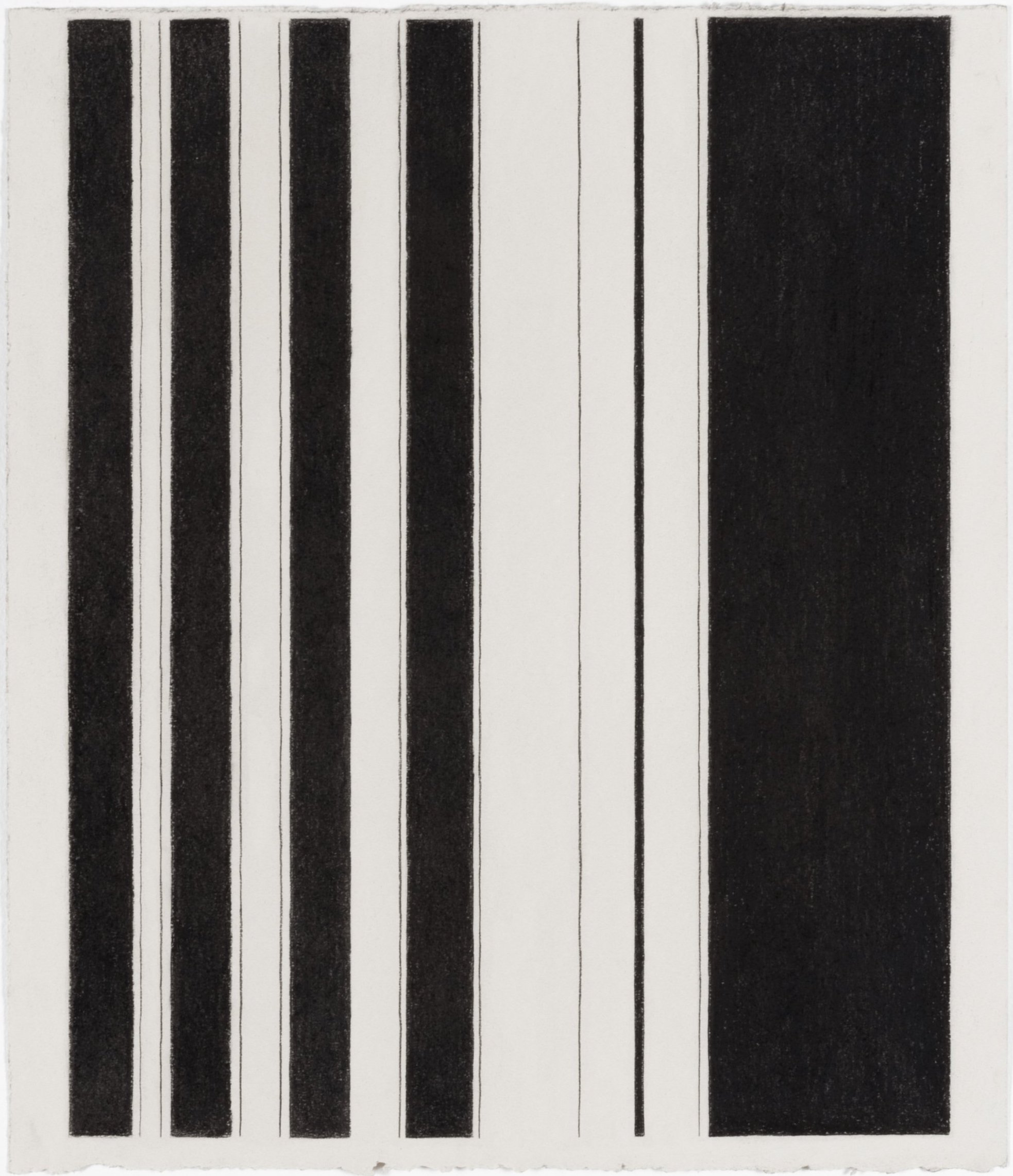

The idea for the Discrete Affection series was to pose the hand with a task that was much more naturally suited for the computer. As I mentioned, computers are excellent at straight lines, rectangles, and even fills. Hands are not. This is especially true when working with a medium like charcoal, where any little inconsistency shows. To start the work, I created an algorithm that generated the basic designs. They look very native to the computer. I used the plotter to lightly (but precisely) draw the outlines of these shapes in pencil on paper. I then tasked myself with lining and filling the shapes by hand using charcoal, as well as I could. What I love about the result is how much this manual process transforms the simple shapes. The richness and complexity is massively increased, and it’s all due to the “error” that is innate to the hand, charcoal, and paper! Because the work has almost nothing else to it, this is the aspect that I hope viewers can focus on.

The idea for Connected for the Moment was almost the inverse of this. This series grew out of studies that I made of hand-drawn lines. I was curious about the typical “defects” in a hand-drawn line: all of the ways in which it tends to deviate away from being perfectly straight. These lines are drawn by fingers, a hand, an arm, and a nervous system that all have their own potential deviations. But they tend to deviate in particular ways. It’s not totally random. In other words, you can study it like a system or a process. I constructed an algorithm for drawing “flawed” lines based on my observations. Connected for the Moment is built around this algorithm. For increased impact, I tend to exaggerate the effects, so it is quite visible. With this work, I use the computer to explore, in some small way, what it means to be a human with a body. It is strange and fascinating to me that algorithms can be such helpful tools for appreciating the natural world.

Thinking of the ever-changing technological advancements in society and the new environments humankind has created (social media platforms, AI-generated content, etc.), how would you describe the relationship between the human experience and generative art?

To me, generative art is an opportunity for artists to fully engage with the most powerful tool that humans have ever created. Historically, programming and software has largely been the domain of extractive commercial entities and advertisers. Generative art is one way that we can instead use programming to explore rich, expressive, and more humane outcomes. It’s no panacea, but I do think that in some ways, it can open our eyes to better possibilities. Or at the very least, I think we can have some fun along the way.