Fashion history is intrinsically embedded in art history—a history that is dressed and located in my imagination as romanticized paintings, colonial adventures and discoveries, intellectual dramas and poets’ dreamy musings. Embedded in my stark memory are the famed paniers captured in Velazquez’s Maids of Honor; Rococo’s fluid grandeur in Watteau’s swinging lovers’ tryst within a profusion of silk, flowers, and leaves; Gainsborough’s portraits in lush chinoiserie fabrics; Neoclassicism’s perfect Roman and Greek aesthetics idealized in Ingres’ portraits. And yet the most personal of these images of cloth is the famed “first” couturier, Charles Fredrick Worth, whose silk cut voided velvet Kimono-like coat, on view through Sunday in Fashioning Fashion, elicited reams of memories for me. It is not often one can be so directly be connected to an historical event or person; but this is my reality.

Worth (house of), Woman’s Opera Coat, 1910–1911, gift of Mrs. Kerckhoff Young

Fashioning Fashion is for me the most personally affecting exhibit in this museum has mounted, now or ever. 111 years after the founding of the House by Charles Frederick Worth in 1857, I, Hylan Booker, became the head designer of this famous London couture establishment on Grovenor St. West 1. The first black couturier in Europe! Having won the year before the much sought-after Yardley Award as the leading British Designer of 1967, I could safely say it paved the way to this fabulous appointment.

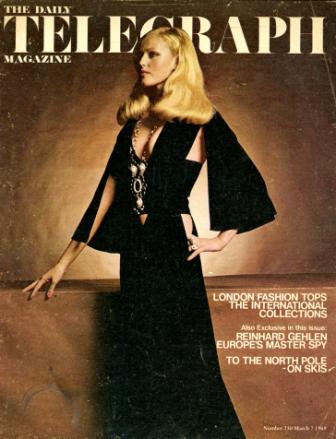

Dress by Hylan Booker, 1969

What Fashioning Fashion so ravishingly makes real through the full cultural forces of technology and its small but equally forceful sheer extravagance, is the power of appearance. The one sure thing in the blood of fashion is the evanescent vanity and the love affair with the “look.” Crafting this melodrama, women are made to embody ideas for desire; the chameleon’s captivating magic, “the muse,” that inspires designers to dream.

Reflecting on my time with the House of Worth, the most striking thing was the time itself. The 1960s were hot and sexy, and Swinging London was the coolest place in the universe—vivacious, vivid, and vital. It feels like everything that we experience now was being born at that very moment. The spirit of women really defined this sense of liberation with a freedom not seen since the 1920s, although far more complex and assured. Here the short skirt, the tights, bobbed hair, and the pill would cut them off from the past as never before. Unknowingly, we were the future. With our own intoxicating background music of the Beatles, the Who, the Rolling Stones, the Lovin’ Spoonful, the Kinks, Jimmy Hendrix, and so many more, a self-reflecting universe seen through Pop art was complete. It was a glorious, uniquely transient moment! And we were the agents, the vanguard, possessing a standard we were somehow expected to maintain. I was the product of the Royal College of Art, as were many of the designers and artists at the time such as David Hockney, R. B. Kitaj, and the Kings Road style maker, Ossie Clark. England was bursting with artistic energy.

If fashion is constantly turning toward its own visions, as Fashioning Fashion so elegantly suggests, than the mood for the earlier Victorian grandeur, that perfect “House of Worth” haute couture look, became my moment in 1999. Suddenly this air, this mood, had evolved a new sensibility—a feeling for a forgotten sense of pomp and circumstance that the great ball gowns of the Romantic Age so naturally represented. For my couture collection for that year, 1845–1865 was the perfect attitude for my romance of fashioning fashion.

Woman’s Dress (robe à transformation), France, c. 1865, purchased with funds provided by Suzanne A. Saperstein and Michael and Ellen Michelson, with additional funding from the Costume Council, the Edgerton Foundation, Gail and Gerald Oppenheimer, Maureen H. Shapiro, Grace Tsao, and Lenore and Richard Wayne

Dress by Hylan Booker, 1999

Hylan Booker