This weekend LACMA added eight new works to its collection through its annual Collectors Committee events. All week on Unframed our curators will be highlighting the objects just acquired.

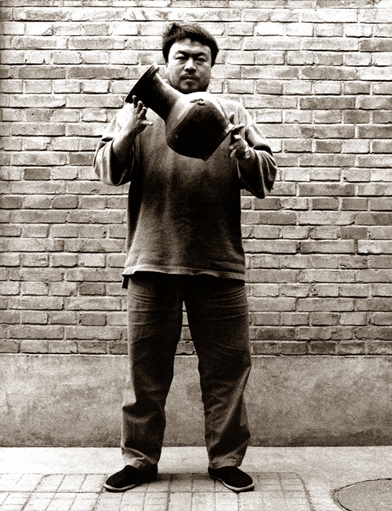

Ai Weiwei, Untitled (Divine Proportion), 2006, gift of the 2011 Collectors Committee, photo: Giovanni Tarifeño, courtesy of Friedman Benda and the artist

On April 3, Ai Weiwei’s human right to free speech—and all other rights—were summarily taken away from him when he was arrested in Beijing. (LACMA, along with twenty-seven other art institutions around the world, urge you to sign this petition for his release. More than 91,000 have signed so far.) The acquisition of Untitled (Divine Proportion) gives us the opportunity to consider Weiwei the artist and thinker—an artist whose ability to poetically transform material into objects embedded with meaningful ideas and consummate beauty assertively raises fundamental questions concerning human existence.

Untitled (Divine Proportion) employs materials and techniques associated with the historical past in order to explore the object in the present. While the type of wood and the way it is crafted recalls the making of utilitarian objects of an earlier era, Weiwei’s contemporary work of art is thoroughly of our moment. In its formal simplicity—the circle being the most common form in diverse societies around the world—and its title, the artist presents us with a contemplative object hinting at a mathematically derived spiritual dimension while remaining fully open to interpretation. Is it a globe, a ball, or just an abstracted work in the form of a circle? One critic has said that, “Overturning practical function transforms [Weiwei’s] pieces into inoperative but strangely elegant mutations that reintroduce the conceit of ornament and ritual back into the domain of art.” I’d agree.

Born in 1957 to a poet father whose leftist leanings led to the family spending the 1960s in Siberia, Weiwei and his family did not return to China until after his father’s “rehabilitation” and the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976. Early in his career Weiwei thought of art as a means of getting away from politics, as well as a means of expressing himself as an individual; once back in Beijing, in fact, he joined the Stars Group, which believed each of their members to be a star in direct confrontation to communist uniformity. Having obviously put himself in the way of politics, as had his father, Weiwei embraced another exile, though voluntarily this time, spending most of the 1980s in New York. Returning to Beijing again in 1993, four years after the events of Tiananmen Square, Weiwei helped establish the experimental art community, the East Village, which also included the artists Ma Liuming and Zhang Huan, whose work recently came into LACMA’s collection thanks to the Los Angeles collector Audrey Irmas. Since then, Weiwei has become increasingly well known; his work constantly probes and pushes aesthetic and political boundaries, often exploring the role of the individual in society through writings and actions, as much as through individual pieces of art and architecture.

Amidst his activism, work as an architect (he was a collaborator with Herzog & de Meuron on the “Birds Nest,” China’s Olympic stadium in Beijing, in 2008) and busy studio practice, Weiwei also continues to make objects—the real heart of all his artistic endeavors.

A collector and connoisseur of Chinese antiquities, Weiwei is fond of using “found objects” in his own work. While this Duchampian practice began when he was in New York, his return to Beijing in 1993 inspired him to turn to Chinese cultural materials and artifacts as an integral part of his art-making process. “I take the constitution and the political situation in China as a readymade,” he has said. In a twist on his hero Marcel Duchamp’s concept of the readymade, which purports that anything can be turned into an object of art, Weiwei introduced the “ancient readymade.” He displaces, recycles, and manipulates, sometimes even destroys traditional objects in order to “make it new.” One of the earliest works in this mode is Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, from 1995, seen here in three documentary photographs of the artist destroying a 2,000-year-old vehicle of cultural tradition. The artist’s belief in iconoclasm as a way of creating new ideas and values is a central facet in his work.

Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn 1/3, 1995, © Ai Weiwei

Less ironic, Divine Proportion is handcrafted from Huanghuali wood, a fine Rosewood used to make furniture during the Qing era, the sculpture is made by a carefully executed tenon and mortise technique perfected during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing Dynasties (1644–1912). This nail-free joinery technique achieves a seamless connection of surfaces regardless of thickness or placement of wood. Made to withstand time, as earlier pieces were in this mode, Weiwei’s Divine Proportion evokes the past though it is built for the future.

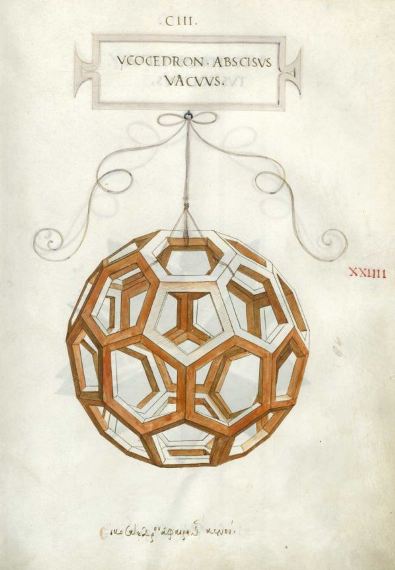

Drawing by Leonardo da Vinci for De Divine Proportione

Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings for The Divine Proportion, made to illustrate Luca Pacioli’s book written in 1509, are some of the first drawings of polyhedra known to humanity. But Weiwei’s object was not originally modeled after Leonardo’s. He was first attracted to the toy his cats played with, which was exactly the same designed spherical object. That sense of playfulness coupled with the historical weight of early geometric drawings unified into a single beautiful object, goes to the heart of Weiwei’s endeavors to successfully combine wit with substantial subject matter in a mute object. The simple form of Divine Proportion is in line with the artist’s architectural projects that evince a clear-cut and precise sense of space.

As in the work of Sol Lewitt or Donald Judd, the extreme regularity of forms and volumes in the Divine Proportion sculptures delimits visual concreteness, and as a result, thoughts are directed to context, meaning, and nature of the material itself.

Later this year, we are proud to say that LACMA is the west coast destination for the artist’s recent project Zodiac Heads/Circle of Animals, a twelve-piece installation of thirteen-foot-high bronze sculptures that represent the zodiac installed at the Old Summer Palace in Beijing, which was looted by the French and British in 1860. Some of those pieces have been returned as national treasures but others are still out there in the world. Weiwei’s work brings them all together again, in a sense. While that piece mends a broken circle together again, Divine Proportion speaks to the circle or globe as an inherently well put together place, strong in its connection and rich in its natural cohesion. Untitled (Divine Proportion) is tentatively slated to go on view by the end of this year.

Franklin Sirmans, Terri and Michael Smooke Curator and Department Head, Contemporary Art