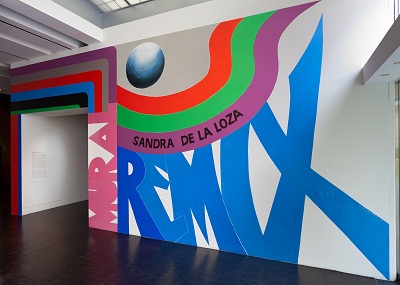

Mural Remix: Sandra de la Loza is LACMA’s fifth contribution to the Pacific Standard Time initiative and one in a series featured in the multi-venue exhibition cycle L.A. Xicano. Chon Noriega, director of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center and adjunct curator at LACMA, spoke with artist Sandra de la Loza about Mural Remix and activating the history of Chicano muralism in Los Angeles.

Sandra de la Loza,” Mural Remix: Unknown, Believed to be by José A. Gallegos, 1975,” funded by Citywide Murals, 2010, © Sandra de la Loza

Your earlier work often exposed the role of official monuments in producing “historical amnesia.” What motivates your current focus on Chicano murals?

I chose to focus on Chicana/o murals produced during the 1970s because that time period lends itself to so many issues that I felt were important to address both within current city politics and Pacific Standard Time’s effort to historicize L.A.’s postwar art history. Many murals are currently faded, peeling, or have been buffed by anti-graffiti abatement teams. This history is neglected and is literally being erased. Given the art circuit’s current interest in socially engaged art, I am aware of the fact that the Chicana/o mural is rarely mentioned or acknowledged as a legitimate art form within L.A.’s art institutions. I also felt the topic was significant given current city politics around public space and wall art. I mean, we live in a city with a moratorium on murals that spends six times the budget allocated to the Department of Cultural Affairs on graffiti abatement. I am interested in history, precisely the ways in which it lingers and can activate the present. I was attracted to the challenge of finding meaningful and relevant ways to activate this history given the current context.

Your work through the Pocho Research Society for Erased and Invisible Histories (PRS) is notable for collaboration. In this piece you have teamed up with several artists, including your older brother, muralist Ernesto de la Loza. Can you say a little bit about the collaborative process and why it is so important to your work in general?

Within Mural Remix, I invited artist Joe Santarromana to work on Action Portraits. I knew Joe first as a professor, then as a friend, and more recently as a collaborator. Joe’s familiarity with my work provided critical insight and helped push my original concepts. His video expertise also helped solve technical issues that really took those portraits to another level. I also thought it was important, given the subject of this show, to bring in a muralist. Through my research, I discovered that a 1970s commercial graphic style, which numerous muralists interviewed refer to as “supergraphics,” was incorporated into murals. I commissioned my brother Ernesto de la Loza, a muralist from that era who is also a billboard and sign painter, to design and paint an exhibition title using this style.

Installation view Mural Remix: Sandra de la Loza, October 15, 2011–January 22, 2012, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Mural Remix not only creates new imagery from incidental elements of 1970s Chicano murals, but it projects this imagery—quite literally—onto the bodies of younger street and graphic artists. What does this multigenerational process say about the possibilities for Chicano art today?

I wanted to acknowledge the persistence of this history. There is no official “school” to transfer knowledge from one generation to the next, yet the impulse persists. Elements of this visual space forged by a previous generation of artists are still very much alive today, albeit transmuted in content, form, and aesthetics. Even if every wall in the city is whitewashed, the seed is planted and will keep surfacing because the impulse is located elsewhere—from within. I think the persistence of wall art is pretty amazing considering that millions of dollars are spent to make it not happen.

Sandra de la Loza and Joseph Santarromana, Action Portraits (installation view), 2011, © Sandra de la Loza, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Explain how this project relates to the Light and Space movement. In some ways Light and Space is the antithesis of Chicano muralism.

Through previous PRS projects, I had begun to explore the subjectivity of history. As an artist entering the archive, I was aware of the power that the historian and curator have in framing a subject, and I wanted to occupy that space and play with both the contextualization and the aesthetics of archival material. I especially wanted to look at the mural through a conceptual frame that wasn’t so much representational but spatial. I had already begun exploring how urban space was shaped by the needs and interests of a capitalist economy. I found Henri Lefebvre’s Marxist critique of urban space particularly relevant in beginning to think about muralism in relation to the architecture of a postwar manufacturing landscape. Estrada Courts, a housing project that became one of the focal points of 1970s murals, was built from military barrack architectural plans during a housing shortage when L.A.’s economy boomed during the World War II economy. So, I wanted to find an aesthetic language that would lend itself toward this spatial understanding of the mural. Since muralism is largely an outdoor art form, I began to think of light and its influence on artists within the region. Through my research, I found an interesting yet not-obvious overlap with the Light and Space movement. Robert Irwin writing about the artists ability to “see and aesthetically order the world as the one pure subject of art” inspired me to begin to name the particular scope and form that Chicano artists created by claiming and transforming the architectural space of Mexican American working-class communities in this city. While Light and Space artists explored ideas of change, transformation, and transcendence through formal means utilizing light, color, and architecture, Chicano artists used city space as their platform. They worked to materially “remake their own reality” through means that were both aesthetic and social. This helped me begin to identify an aesthetic language that was both spatial and social within 1970s era murals that I try to make visible in the exhibit.

What next?

Through Mural Remix and a previous project, The Art of Lockpicking, the Lockpicking in Art, which I exhibited in Cairo, I have begun to explore L.A. urbanism. I’m interested in continuing that pursuit. I am also currently working on a public art commission with artist Arturo Romo. We are merging our interests in ecology and social issues for a work that will be permanent and long lasting. I am excited about all the work being done in Los Angeles—many that aren’t necessarily art-based—that critiques and reimagines the urban landscape. I want to participate in the creation of a new urbanism that is fueled by values of social and environmental justice.

Chon Noriega, Director of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center and Adjunct Curator at LACMA