Our beautiful Japanese Pavilion—with its style and air of something ancient, yet nevertheless modern—houses three-thousand-year-old vessels, jars, Buddhas, ancient animal guards, fierce Samurai armor, and deadly sharp Samurai swords. However, within a few steps, in Fracture: Daido Moriyama, we are flung and plunged into twentieth- and twenty-first-century Japan—an experience somehow disquietly familiar, eerily alien, and weirdly futuristic, with shades of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner.

Daido Moriyama, Untitled (trash cans), printed 2009, courtesy of Courtesy Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, © 2012 Daido Moriyama

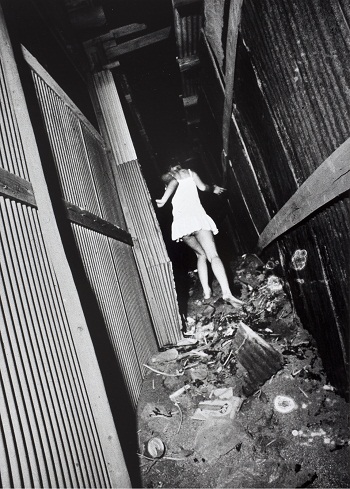

In Memories of a Dog, Daido Moriyama—with a slight smile—declares, “I’m like a stray dog,” unconcerned with the allusion. His black-and-white images are not memory, but the stylized theater of urban reality caught as moving targets by a modern man, testosterone-rich and unapologetically masculine. The striking drama as the white glares to diffusion of the black images—be they objects or people—injects loads of glittering glamour to the odd collection of groupings. For instance, trash-canister tops are in the foreground of a group of people as if something nefarious were present. The human condition is made provisional, alluring, and infinitely mysterious. Sometimes it’s obliquely erotic and other times straight up and in-your-face sexual—and always through a scrim of menace. There’s a fierce motion in his photos, blurring to abstraction on one hand, yet with the intense need to capture the immediacy and vitality of living presence on the other.

Daido Moriyama, Kariudo (Hunter), 1971, printed 2009, courtesy of Courtesy Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, © 2012 Daido Moriyama

Like all voyeuristic imagery, he makes you a party to his vivacious lens, and thus you are made predator in Hunter. You are unable to turn away from the giant lips, their pout like creased pillows. It’s hallucinogenic, as a sullen chubby boy’s face presses forward into the frame. Wired fences are so close as to form a grid, while the vague cars and buildings are mere palettes of grays and charcoals. The world is shadows, broken into pieces and seen through the zoom lens of confrontation. Mountainously sensual rear ends in jeans or fishnet stockings force themselves on you. It’s physical, and it’s intimate.

Daido Moriyama, Untitled (shadows with tires), printed 2009, courtesy of Courtesy Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser, © 2012 Daido Moriyama

Moriyama, more than most, to me, epitomizes the realization that photography is an alien third eye with the power to create an alternate reality—a reality which is as repulsive as it is seductively attractive. It’s a reality we know is exaggerated, dipped in a lugubrious ink the color of midnight—those down-and-dirty blues which we associate with the dark side of American life. His Tokyo—or rather his neighborhood, Shinjuku—is made somehow precious, vulgar, clownishly regal, and elegant. Take the picture of the coat covered in pearl buttons—where he shoots in perfect relationship to the light, somehow sharing the darkness—making it almost weightless and ethereal, kind of heavenly. Texture abounds in his images. Old dogs and old tires are transformed into junk beauty or elegant brutal realism. It’s our safe passage to the other side, though we are uneasy and somewhat fearful. Japan is no longer white cranes fluttering across a sea-green kimono or white-masked smoky mythic dramas on folded silk screens taking us out of our hard metal world of acid-washed jeans and plastic dreams.

Daido Moriyama, Shinjuki #11, 2000, courtesy of Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, © 2012 Daido Moriyama

Daido Moriyama repositions us with his macho zing and daring honesty; he sees the beauty where we would look elsewhere, and plays in the dark. You get to walk with him in his video—it’s close contact. You sense the flash of his captured moments like some adrenaline-high quick-draw artist. He’s a modern-day samurai, eyeing with laser speed the disjunctive elements. In spite of this, it’s an embrace. And then you squeeze down the narrow stairwell when he declares the city a sexual entity, which from his point of view it could hardly be otherwise.

Moriyama’s photography braids us constantly into the fabric of the singularity of our actual “looking” and ties the knots to our deepest sensual signals. For those split seconds, our eyes are amoral, panoramic, and restlessly inventing beauty. But for Moriyama they are not seconds but a jet stream of a life in motion—and at some existential level—making all encounters mean something in the deep well of his visual cortex.

Hylan Booker