Perhaps it's the overwhelmingly enthusiastic response to the Mosaic Skull on view in Children of the Plumed Serpent or maybe it’s the museum's proximity to the Page Museum’s treasure trove of fossils—whatever the reason, I’ve got skulls on the brain (pun unfortunately intended). Once upon a time, a post about skulls would have seemed better suited for autumn. That is, after all, when Halloween haunts us with deliciously spooky skeletons and Día de los Muertos wields memento mori to commemorate both our own mortality and those we have lost. However, the skull's iconographic popularity now seems to be a year-round phenomenon.

Having the privilege of perusing LACMA’s galleries each day, I’m reminded that skulls have had a longstanding role in art history, long before Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God triggered a cranium craze in the art world and residually throughout pop culture.

Allow me to guide you through a mere sampling of skulls in LACMA’s collection:

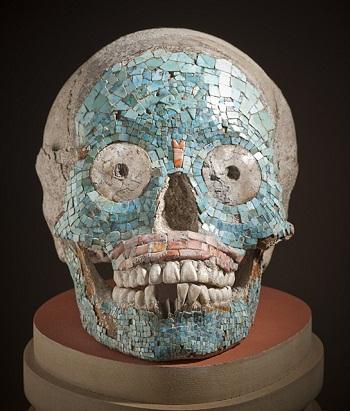

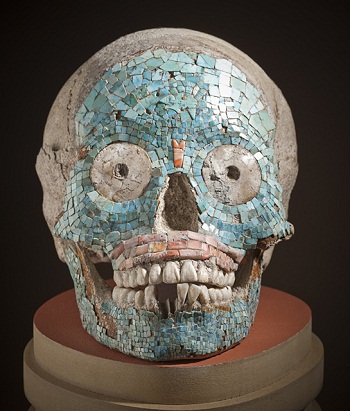

Mosaic Skull

On View: Resnick Pavilion

The aforementioned Mixteca-Puebla Mosaic Skull in Children of the Plumed Serpent is specked with turquoise, jadeite, and shell and is thought to have been produced between 1400-1521 in Mexico in veneration of Mixtec ancestors. Such ornate tributes trumpet the wealth of the commissioner, as they highlight the exchange of luxury goods between Mexico and the Puebloan region of New Mexico, from where the turquoise originated. Children of the Plumed Serpent closes on July 1, so be sure see this spectacular artifact if you haven’t already.

Mosaic Skull, Mexico, Western Oaxaca or Puebla, Mixteca-Puebla Style, 1400-1521, gift of Constance McCormick Fearing

Horse’s Skull with Pink Rose, Georgia O’Keeffe

On View: Art of the Americas building, Level 3

O’Keeffe’s "bonescape" compositions from the 1930s were a result of inquisitive scavenging during her time in New Mexico. Intrigued by fragments of sun-bleached animal skeletons found in the desert and fabric flowers left on graves in Hispanic cemeteries, the artist collected these objects and traveled with them to her studio in New York. There, she began her foray into still life paintings of bones with a particular affinity toward skulls. For O’Keeffe, the durability of skeletons and fabric flowers represented the eternal, parched beauty of the American Southwest.

Georgia O’ Keeffe, Horse’s Skull with Pink Rose, 1931, gift of the Georgia O’ Keeffe Foundation

Head-Skull, Alberto Giacometti

On View: Ahmanson Building, Level 3

In the early 1930s, Alberto Giacometti made significant contributions to surrealist sculpture. In Head-Skull, he flattened the planes of his approximately life-sized subject, thus eradicating the standard curvature associated with the human skull. Instead, his rendition appears Cubist—almost architectural—in its smooth geometry and examines the beautifully complex semiotic implications of a skull in both life and death.

Alberto Giacometti, Head-Skull, 1934, partial, fractional and promised gift of Janice and Henri Lazarof

Skull Rack, Papua New Guinea

On view: Art of the Pacific, Ahmanson Building, Level 1

Despite its smiling face, this one is a bit grim. The sacred agiba—a flat, carved, painted, wooden figure—comes from the Kerewa People of Papua New Guinea and exists to showcase skulls procured by a given clan. Headhunting was a central part of religious practice in historical Kerewa tribes, and raids were carried out, as I read in Island Ancestors: Oceanic Art from the Masco Collection, “in preparation for initiations and for such rituals as the inauguration of a new ceremonial house or the completion of a canoe.” Yikes.

Papua New Guinea, Gulf Province, Skull Rack (agiba), c. 1900, purchased with funds provided by the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation with additional funding by Jane and Terry Semel, the David Bohnett Foundation, Camilla Chandler Frost, Gayle and Edward P. Roski and The Ahmanson Foundation

The Magdalen with the Smoking Flame, Georges de La Tour

The skull is an accessory in this French baroque masterpiece by Georges de La Tour, helping to set the tone for Mary Magdalen’s contemplation of penance and the afterlife. De La Tour’s iconic painting is not currently on view at LACMA, as it is currently vacationing in Europe as part of the Bodies and Shadows: Caravaggio and His Legacy tour.

Georges de La Tour,The Magdalen with the Smoking Flame, c. 1638–1640, gift of The Ahmanson Foundation

Luckily, we don’t have to wait long to celebrate its return as the same exhibition opens at LACMA on November 11.

Stephanie Sykes, Communications Manager