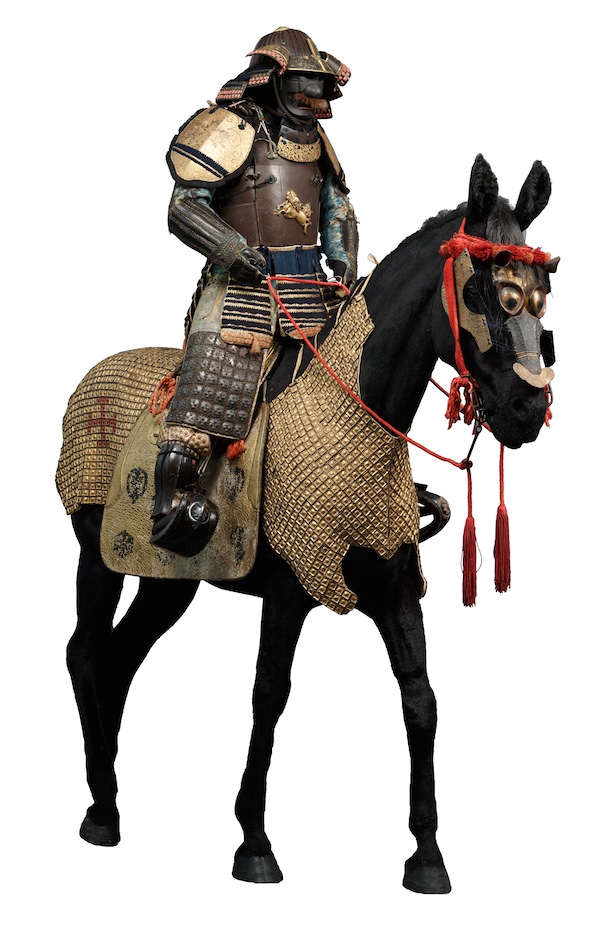

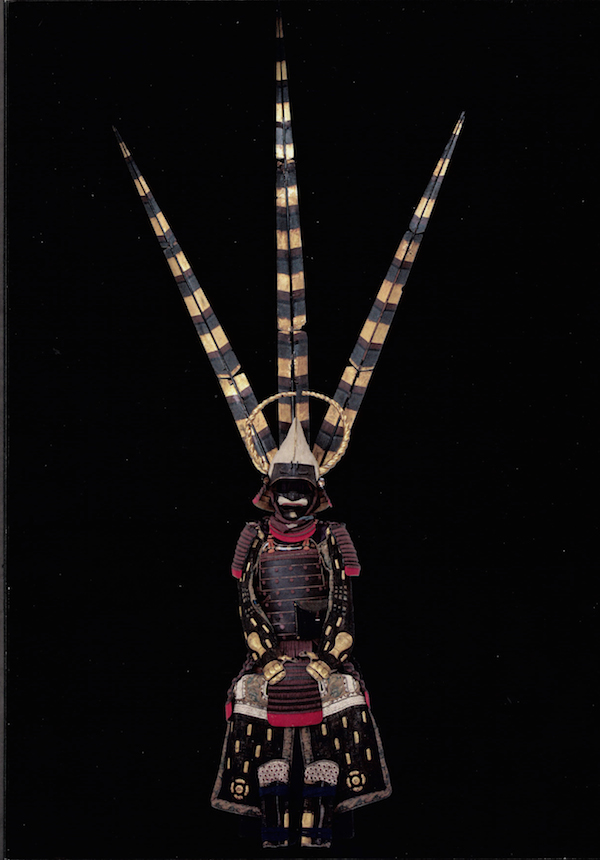

LACMA presents the Southern California premiere of Samurai: Japanese Armor from the Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Collection, a major exhibition featuring battle gear made by high-ranking warriors and daimyō (provincial governors) from the 12th through the 19th centuries. On view in LACMA’s Resnick Pavilion, the exhibition traces the evolution of samurai equipment over 700 years through more than 140 objects of warrior regalia, including 20 full suits of armor, elaborate helmets and face guards, and life-size horse clad in armor. Objects from the exhibition come from the Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Collection in Dallas, one of the most comprehensive private holdings of samurai armor in the world, encompassing more than four hundred pieces and spanning 10 centuries.

Japan ended its policy of mandatory military service in 792. Thereafter, provincial landowners had to rely on their own private forces for defense, a situation that gave rise to the samurai class. For nearly 700 years, beginning in 1185, Japan was governed by a military government, led by the shogun, ruling in the name of the emperor. Samurai warriors were loyal to individual daimyō—provincial lords with large hereditary land holdings. In 1600, after periods of clashes between rival clans, the Battle of Sekigahara paved the way for Tokugawa Ieyasu to unify Japan and establish a new shogunate. Fifteen shogun from the Tokugawa family ruled over a period of peace lasting some 250 years.

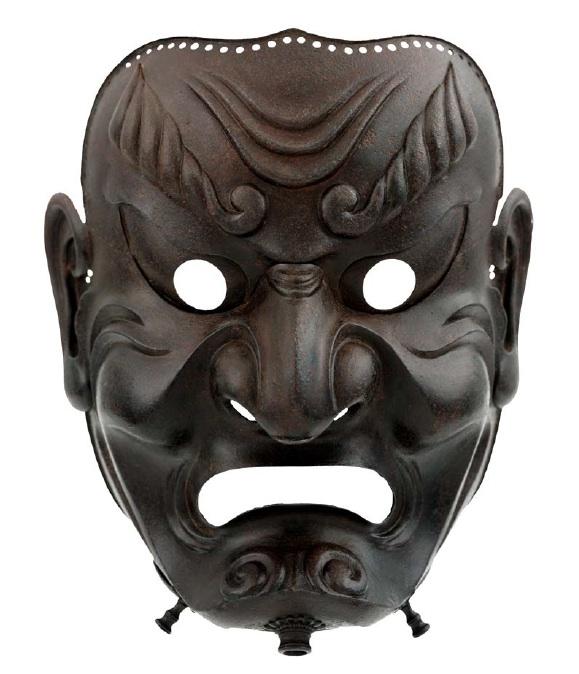

During the subsequent Meiji Restoration in 1868, the emperor reasserted his authority as supreme ruler, and the samurai as an official elite class was dissolved. The term “samurai” comes from the verb saburafu, which means “to serve by one’s side.” Initially, samurai were armed servants; later, they became experts in warfare. Samurai armor consists of a helmet (kabuto), mask (menpō), and chest armor (dō) combined with shoulder guards, sleeves, a skirt, thigh protection, and shin guards. Additional articles, including a sleeveless surcoat (jinbaori), complete the set, which might weigh between 20 to 45 pounds total. Many materials were required to produce a suit of Japanese armor that was as beautiful as it was functional. Iron, leather, brocade, and precious and semiprecious metals were often used. Several artisans worked for many months to create a single suit of armor.

Samurai: Japanese Armor from the Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Collection features both practical armor used from the Kamakuru (1185–1333) through the Momoyama (1573–1615) periods as well as the largely ceremonial objects of the Edo period (1615–1868). In keeping with LACMA’s efforts to collaborate with local firms, the museum worked with Kulapat Yantrasast of wHY architects to create a design for the exhibition that captures the kinetic energy of the objects through unique mountings, the use of models, and nontraditional modes of presentation. Additionally, across campus at the Pavilion for Japanese Art, a companion presentation, Art of the Samurai: Swords, Paintings, Prints, and Textiles, features samurai swords, sword fittings, and other weaponry from local collections; color woodblock prints depicting warriors in battle from LACMA’s collection; and a selection of garments worn by samurai culled from the museum’s Costumes and Textiles Department.

Samurai: Japanese Armor from the Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Collection is organized by the Ann & Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas.

A version of this article originally appeared in the fall 2014 (volume 8, issue 4) of Insider, LACMA's magazine for donors.