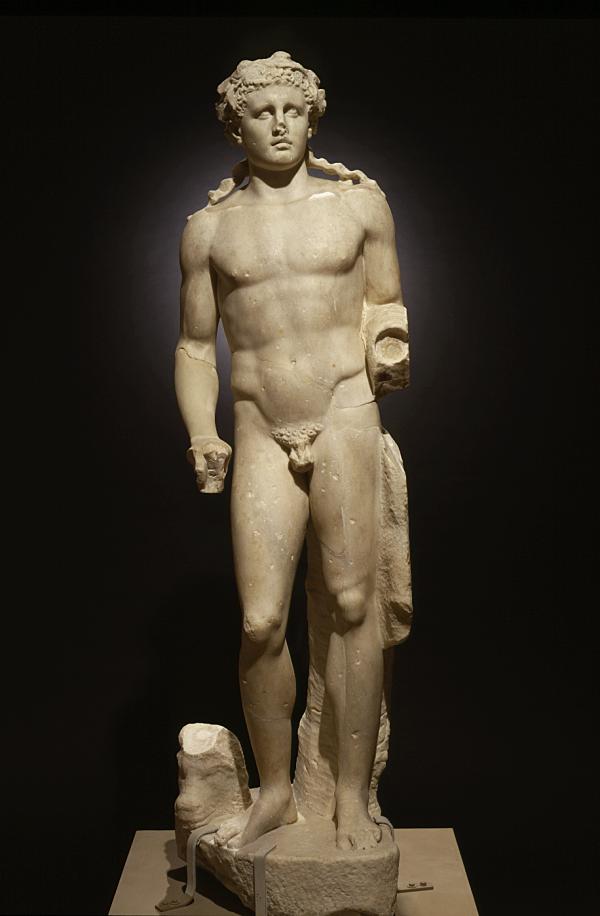

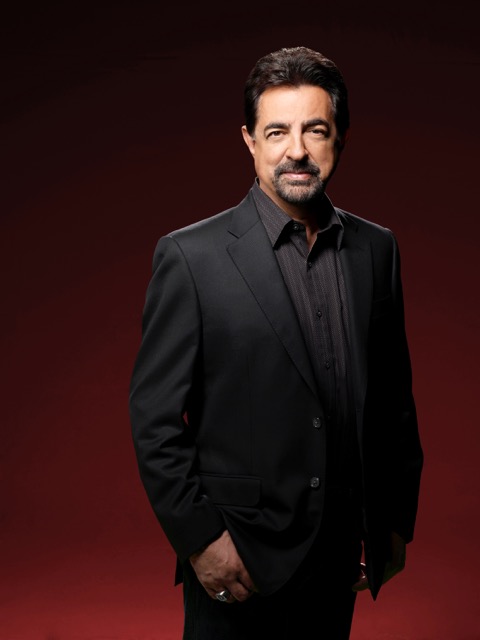

Gabriele Tinti, an Italian poet, has composed poems inspired by mythology and ancient artworks in museums including the Getty and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His epic poem, "Hercules," was recently performed by actor, director, and producer Joe Mantegna in LACMA’s galleries, with the mythic figure—in the form of The Hope Herakles, an ancient Roman copy of a 4th-century-BC work by the Greek sculptor Skopas—looking on.

I contacted Tinti to learn about his creative process and connection with Classical art, and spoke to Mantegna about his attraction to Tinti’s project.

Gabriele, what is it about Hercules that appealed to you and inspired you to write a poem about the figure?

Hercules—hero and demigod of Greek mythology, the strongest of men—has been described in various ways in literature. Homer, in the Odyssey, presents him as brutal and violent; Hesiod, in his The Shield of Heracles, as a figure resistant to all barbarity, a civilizing hero. Euripides, in his tragedies, portrays him as fragile precisely at the moment he reaches the peak of his glory. Sophocles’s Heracles is suffering, and finds himself alone before death, the last of his labors, which he confronts without tears, with supreme courage.

Taking a cue from the latter, I have tried to imagine the interior torment that the hero experiences in the dramatic, last moments of his life—to regard his death as a fulfillment, even a celebration: a death in which his spirit and virtue still glow (as Nietzsche has put it).

The intense melancholy of Herakles by Skopas, the sunken eyes beneath the arched eyebrows, those pathetic eyes turned toward the sky, led me to imagine Hercules in the crucial moment when he found himself faced with death. It is in that moment that he takes onto his shoulders all the suffering of the world, freeing it.

You previously composed a poem inspired by Seated Boxer, a Greek sculpture from the 3rd century BC, at the Getty. What interests you about these communications with the ancient world?

The icons of today, words, writing, have lost their religious intensity, their “aura.” They are none other than a running back to that magical “sign of that which has disappeared,” to use a phrase from Baudrillard. It is probably true, as he wrote, that “art as such will perhaps have been only a parenthesis in the history of mankind.” And the poet may by now be nothing but a jester.

My poetry is an attempt to counter the poverty of erudite amusement and linguistic play to which it is confined, and to try to go back, if it were possible to do so today, to singing tragically. Tragic songs were a preparation for death, a divination of the forebears, a glorification of failure.

.jpg)

What can poetry contribute to the understanding of artworks that critical analysis can't?

The aim of my series of ekphrastic poetry is to reactivate the now-lost aura of the work of art that no longer exists. In this way the work of art takes on new life, and the poetry finds an ideal body in which to take form.

On the other hand, critical analysis always restricts the aesthetic and cultural range of a masterpiece. Because every time a work is analyzed, it is defiled: an attempt is made on its irreducibility.

Poetry is never reduced to an explanation. Real poetry is always beyond any calculation, any system, any geometry: it is incompleteness, evocation, lament, thrill.

Joe, tell us what motivated you to become involved in this project.

I’m proud of my Italian heritage, because I’m close to my relatives in Italy. There’s so much more to Italian culture than The Godfather and Al Capone. Of course, I don’t discount that aspect of it. As an actor, I’ve done those kinds of roles. [Editor’s note: Mantegna, who stars in Criminal Minds on CBS, played Joey Zasa in The Godfather: Part III.] But I want to make sure people understand the depth of the culture.

At LACMA, and places like the Italian Cultural Institute, we’re talking about people who make it their purpose in life to propagate cultures of the world. These places let people experience the past in the present, which impacts the future. All of this is important, especially as you get older. I’m in a position to speak from that perspective. We can’t let the museums, the libraries, the institutes of learning go by the wayside.

Right now, in the Middle East, we’re seeing whole cultures being wiped out. It makes me think of the Library of Alexandria in Ancient Egypt—all those things we’ve lost that we wish we could get back. I want to feel that I participated in keeping cultural places alive.

Visit The Hope Herakles (Hercules), and other works from LACMA's collection of Greek, Roman, and Etruscan art, including The Hope Athena and the Lansdowne Artemis, in the Ahmanson Building, Level 3.