With the flurry of recent exhibitions devoted to Latin American art nationally and internationally, many works from our collection are now on loan. Key Mexican modern works were lent, for example, to the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Paint the Revolution, while our iconic Flower Day by Diego Rivera became a centerpiece of LACMA’s Picasso and Rivera: A Conversation Across Time. Other works—ranging from Spanish colonial to modern Mexican decorative arts will soon be lent to various exhibitions across Southern California as part of Pacific Standard Time:LA/LA, an ambitious initiative organized by the Getty devoted to Latin American and Latino art.

To accommodate these loan requests, we gave our own galleries a small makeover and brought out works acquired over the past five years—several on view for the first time. The first gallery is devoted to modern highlights and features two special recent gifts, including The Painted Cock (El gallo pintado) by the Cuban avant-garde artist Mariano Rodríguez (known as Mariano). The work depicts a majestic rooster, with his feathers painted in the colors of the Cuban flag. A quintessential symbol of Cuban pride and masculinity, this iconic image is also tied to traditions of rural guajiro farming communities and the Afro-Cuban religion of Santería. It is one of the most important works by Mariano outside of Cuba.

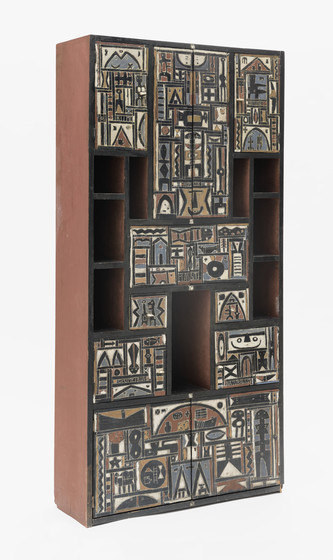

Another highlight is Gonzalo Fonseca’s Constructivist Cabinet (Mueble constructivista). Fonseca was a member of the legendary Taller Torres García (TTG), an arts-and-crafts workshop established by Joaquín Torres-García in Montevideo in 1943. Torres-García created a Universal Constructivist art by integrating universal symbols into his abstract compositions. Inspired by the Bauhaus and other workshops such as Jugendstil and William Morris’s Arts and Crafts Movement, Torres-García also sought to abolish the distinction between fine and applied art, and encouraged artists to apply abstraction indistinctly to painting, sculpture, decorative arts, and graphic work, for example. Universal Constructivism represented a whole philosophy of life that depended on the ritual application of abstraction based on systems used in ancient cultures. The grid and the symbols were therefore imbued with profound spiritual meaning. Fonseca shared Torres-García’s interest in indigenous arts, and in 1945 traveled along with other members of the TTG throughout South America to study pre-Columbian art, an experience that affected his formal and theoretical approach to art, including LACMA’s cabinet.

For the first time, we are also devoting a gallery to works from the 1960s, a turbulent decade marked by military conflict, political mobilization, and social uprisings. The Vietnam War and its unprecedented media coverage, for example, elicited a strong reaction from artists across the globe. Working in New York and Paris, the Chilean artists Guillermo Núñez (b. 1930), of whom we recently acquired two paintings, and Roberto Matta (1911–2002) created poignant works that evoked the violence and turmoil of the times.

Although Matta is best known for his Surrealist works of the 1930s and 1940s, in the 1960s he became exceedingly aware of the atrocities of war, racial discrimination, and the destructive potential of mankind. His iconic Burn, Baby, Burn is inspired by the Watts riots, an important and dark episode of Los Angeles history. The riots erupted in 1965 when a California Highway Patrol officer arrested a black man on charges of drunk driving. Soon after, thousands of people began protesting the discriminatory practices of the LAPD, reflecting the profound racial tensions that existed in the city. The cry “Burn, baby! Burn!”—coined by the charismatic radio DJ Magnificent Montague, who shouted it every time a piece of soul music excited him—was appropriated by protesters during the arson that marked the revolt. Matta’s Burn, Baby, Burn is a powerful indictment of violence and a manifesto for peace.

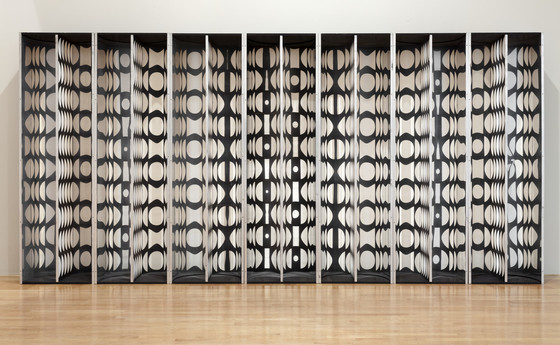

Despite the political unrest, the 1960s was also an era of optimism and experimentation. Following World War II, Paris reemerged as an international hub that attracted many artists from Latin America. Born in Argentina, Julio Le Parc (b. 1928) moved to the French capital in 1958, and in 1960 co-founded the Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (Group for Visual Art Research, or GRAV), which rejected the elitism of traditional art and the concept of the artist as a solitary genius. GRAV experimented with new materials and a range of kinetic and optical effects, creating works that moved—literally, through the use of modern technology and the incorporation of mechanical devices, and virtually, through the eye of the viewer. Le Parc’s Mural: Virtual Circles is newly installed following its showing in the artist’s recent exhibition Julio Le Parc: Form into Action in Miami.

Argentinean-based artist Gyula Kosice (1924–2016) was also at the forefront of experimentation. He employed water in many of his bold kinetic sculptures, reflecting his interest in science, technology, and utopianism. Hydroactivity (Hidroactividad), includes a hemispheric plastic container in which water is constantly recycled against a dark panel peppered with glowing lights. The work embodies Kosice’s exploration of the “architecturalization” of water, and his fascination with space travel and the idea of creating a city suspended above the ground to accommodate the planet’s overpopulation. Kosice even traveled to Washington to consult NASA about the viability of his project!

LACMA’s upcoming PST exhibition Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915-1985 will include a number of Mexican modern silverworks from our significant holdings in this area, giving us an opportunity to bring out some recent acquisitions, including William Spratling’s (1900–1967) Needle Necklace. Following the model of his highly successful workshop of Taxco established in 1931, where he employed hundreds of local artisans and created a thriving local industry, in 1945 Spratling was invited by the United States Department of the Interior to establish a crafts industry in Alaska. The impact of Spratling’s Alaska experience is evident in several of his later designs, including this elegant necklace with stylized silver and obsidian needles that clearly reference the tips of javelins.

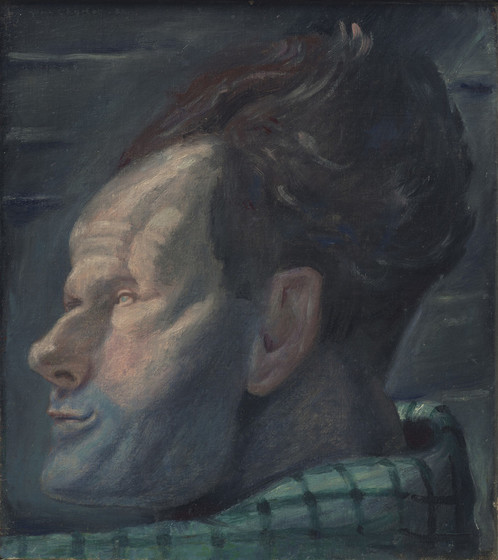

A recent acquisition by another expatriate active in Mexico is the small, yet powerful portrait of the celebrated Russian film director Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948) by Jean Charlot. Born in France, in 1921 Charlot moved to Mexico, where he became and important figure of the Mexican mural movement. A decade later he met Eisenstein, who was working on the film ¡Que Viva México!, and the two struck up a close friendship. Here Charlot vividly captures the filmmaker’s character: he is portrayed deep in thought, looking out at an imaginary horizon, wearing a workman’s shirt to emphasize the idea of the artist as laborer—a key notion of social realism and the mural movement. For more on this captivating portrait and the story of how it was accessioned into LACMA’s collection, read an interview with the artist’s son.

Stay tuned for upcoming posts about other recent acquisitions of our expanding collection of modern art from Latin America—from Mexico to Buenos Aires to Chile.

Visit LACMA's Latin American art galleries in the Art of the Americas Building, Level 4.