A newly discovered painting by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654) portraying the death of Cleopatra has been installed in To Rome and Back, Individualism and Authority in Art, 1500–1800. Marking the only time the painting has been exhibited in at least a century, its loan to LACMA from a Los Angeles private collection introduces the public to an important work by the Roman painter. Artemisia became a successful artist in an era when women were largely prohibited from working as professional craftspeople in any field. While most women artists of her time were typically only permitted to produce portraits and still life paintings, Artemisia was well known for monumental history paintings, especially those featuring legendary female heroines.

The painting on display in To Rome and Back represents the death of the Egyptian pharaoh Cleopatra, delivered by a self-inflicted asp bite. Her hand that held the serpent has already greyed and fallen limp, indicating that we are witnessing the beginning of the pharaoh’s expiration. Cleopatra’s body fills the horizontal composition, parallel to the edge of the lace-trimmed sheet on which she lies. The rich detail and texture of the fabrics resembles Artemisia’s treatment of the luxurious garments in her Esther before Ahasuerus in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which she painted around the same time. The two paintings also share dramatic contrasts of light and dark, characteristic of Artemisia’s circle of “Caravaggisti,” artists who were influenced by the work of Caravaggio (1571–1610). Light falls deliberately on Cleopatra’s chest, highlighting the dramatic crux of the narrative: the asp drawing blood from her breast.

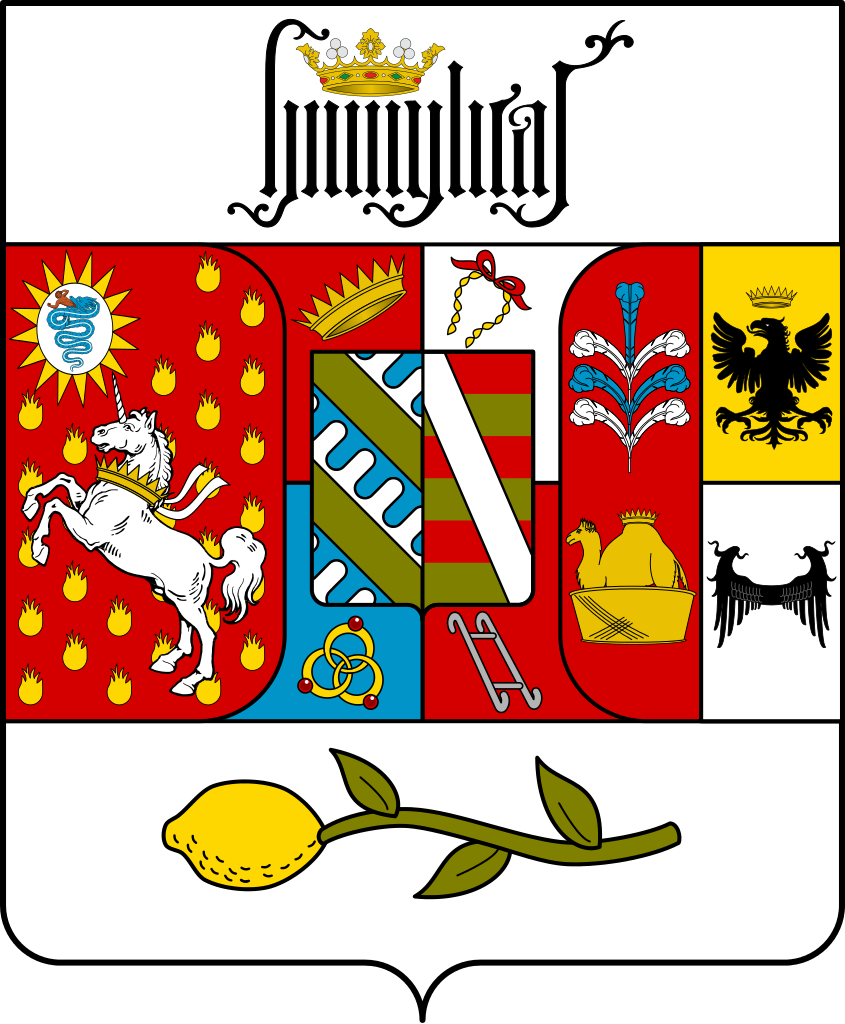

Especially intriguing in Artemisia’s Cleopatra are the inclusion of heraldic symbols from the Borromeo coat of arms along the side of the velvet pillow on which she lay her head: a golden crown, the family motto “Humilitas” in golden Gothic script, and three interlocking rings. The presence of the coat of arms in the Cleopatra opens up new possibilities for research into her relationship to the Borromeo family and the circumstances of the painting’s commission. The House of Borromeo was a major aristocratic Italian family whose members included Carlo Borromeo (1538-1584), who served as Archbishop of Milan and was later canonized as a saint. Artemisia must have felt that it was important to foreground the Borromeo patronage of the painting, as the crown on the heraldic pillow is echoed by the one worn by Cleopatra herself.

While she has often been hailed as an icon of feminist empowerment, Artemisia lived hundreds of years before the women’s rights movement. Artemisia was, however, acutely aware of the prejudices and disadvantages facing women artists in her time. Writing to a patron in 1649, she remarked of her forthcoming work: “this will show your Lordship what a woman can do.” In one of her most well-known paintings, Judith Beheading Holofernes, she sought to demonstrate her artistic capabilities in response to Caravaggio’s earlier painting of the same subject. While Caravaggio shows Judith effortlessly beheading Holofernes in disbelief as her older maidservant looks on, Artemisia represents two strong young women exerting significant effort to execute the decapitation. While she completed the painting in Rome, Artemisia painted Judith Beheading Holofernes as a commission for Florence’s Grand Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici. The painting won her great acclaim, and she later became the first woman to become a member of the Academy of Art and Design in Florence.

Artemisia is significant in art history as an artist who broke new barriers for women in her profession and pioneered the representation of powerful heroines. Don’t miss your chance to see Artemisia’s Cleopatra while it is on view at LACMA!

To Rome and Back: Individualism and Authority in Art, 1500–1800 is on view in the Resnick Pavilion through March 17, 2019.