Earlier this year, after three-plus years of inventorying, two-plus years of packing, and more than 300 truck loads, LACMA’s Collections Management team safely completed the relocation of artworks previously stored on the east campus. They were moved to several offsite storage facilities in preparation for construction of the new building for the permanent collection. While each person on the team can describe their favorite objects and most impressive (or most frustrating) packing projects, we’re all thrilled that over 125,000 works of art are safely relocated and ready for long-term storage.

While a portion of the Costume and Textiles (C&T) collection was already stored at an offsite storage facility, 20,000 objects were onsite at LACMA and needed to be inventoried, packed, and relocated. Inventorying and packing an encyclopedic collection means there are many treasures to uncover. However, it can make developing a cohesive packing system difficult. One of the problems we faced was how to pack and move several thousand small accessories safely and efficiently. This included everything from 18th-century eyeglasses and buckles to 20th-century jewelry and handbags. The goal was to create a system that was consistent but also appropriate for objects of myriad shapes, sizes, materials, and construction.

During the PACMA project, the team responsible for packing 3D artworks and artifacts developed a method for rehousing objects using archival blue board trays with Ethafoam dividers to store large quantities of small objects in one container. I worked with this team to learn their system, and along with Associate Collections Manager for Costume and Textiles Rachel Tu, I figured out how we could adapt it to suit the needs of the C&T collection.

We decided to refit our standard small costume boxes (6x30x18 and 6x40x18 inches) so, when possible, we could stack multiple trays of objects into one container. The base of the trays were double-wall archival blue boards that had been cut to fit the interior dimensions of the boxes. Next, we glued microfoam or Volara to the surfaces to create a cushion for the objects and to absorb vibration in transit.

Before we built up the sides of the trays, we sorted the objects by type, date, and size. By keeping similar items together, we eliminated concerns about how the objects might interact with one another in long-term storage. For instance, it was important to separate the metal pieces from the plastic ones to avoid off-gassing from the plastics.

Objects of similar heights were grouped into two inch, three inch, or four inch trays. Taller objects were stored without trays because it was not possible to have multiple layers in the same box. Ethafoam strips were then cut into corresponding widths for the edges of the tray and to serve as dividers between objects. Having Ethafoam strips taller than the objects was necessary so the tray above would rest on the foam rather than on the artworks below. Ethafoam edges and dividers were glued down with enough space around each object to allow the artworks to be easily removed.

Eyewear

Eyewear containing glass were separated from those made of plastic. Glasses were removed from their cases and wrapped in tissue with the cases being stored in adjacent cavities. Glasses made with plastic lenses were stored in individual trays without tissue, which has a tendency to stick to plastic as it ages. Instead, we used mylar as a barrier between the glasses and foam with twill ties securing the objects in place.

Buckles

We adapted this same basic structure to house a large variety of objects. For buckles, once the foam dividers were glued down, each cavity was filled with a pair individually wrapped in tissue with the object’s number on the outside. The buckles were then secured and loosely tied with cotton twill tape and the cavity filled with tissue to further reduce movement.

Jewelry

Sorting jewelry between coordinated sets and individual pieces brought order to the large collection, with the latter organized further into earrings, bracelets, brooches, and necklace groups. Keeping jewelry sets together makes it easier to access all the pieces at once. Jewelry was wrapped in tissue and housed in individual bags.

Handbags

Due to the variety in shape, size, and material, handbags created a unique problem. Those with internal structure but without surface decoration were wrapped in tissue and stored on their sides with tissue filling out any extra space in the cavity. Handbags from the 20th century often have coordinated mirrors and combs. In those cases, combs were wrapped in tissue while mirrors were sandwiched between two pieces of Volara and wrapped with twill ties. We stored them inside of the bag and then added tissue to keep the internal pieces from moving around in transit.

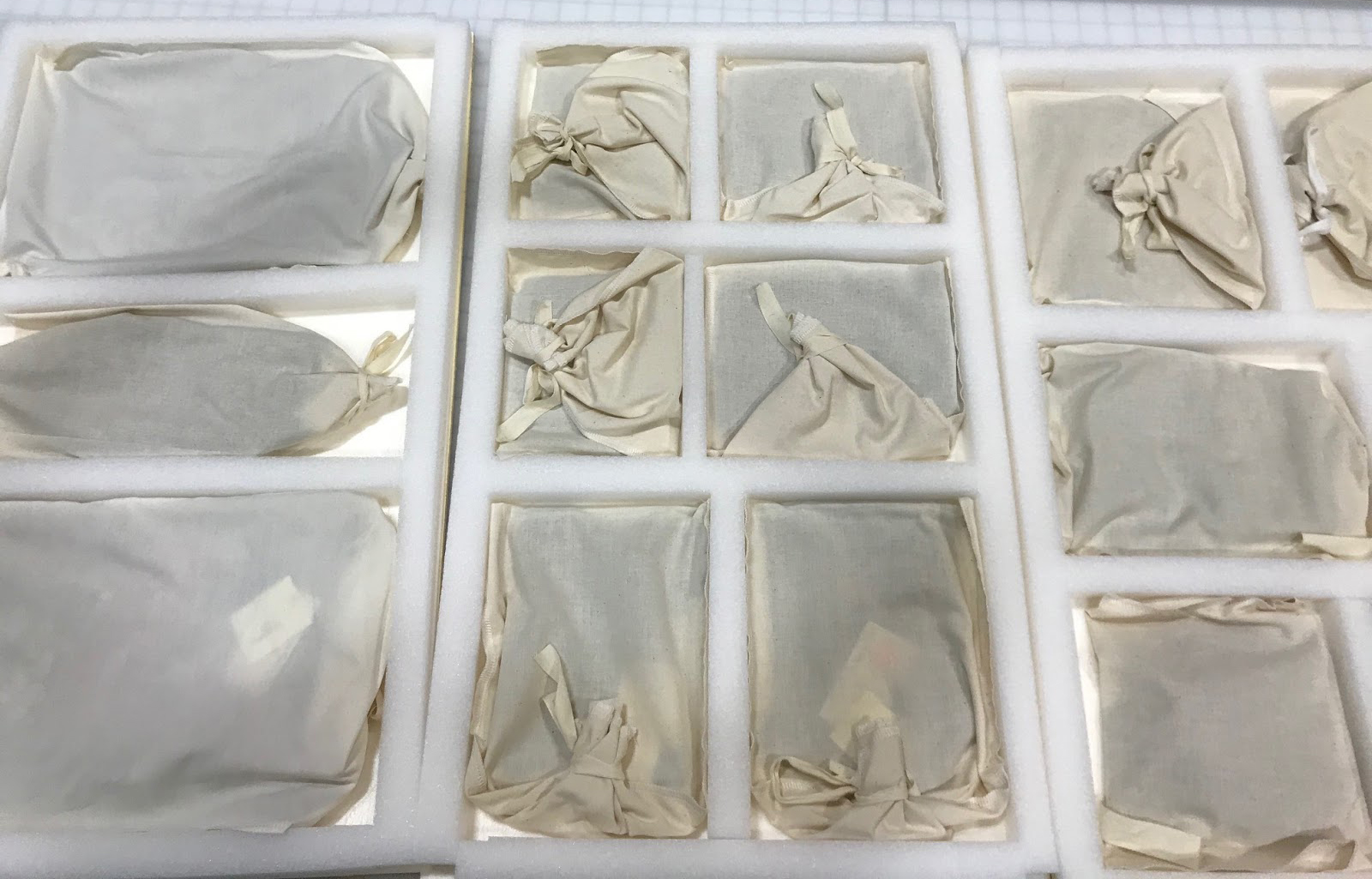

Hard handbags with surface decoration, such as beading, were stored in muslin bags with twill drawstring ties for protection. Custom-made by Junior Collections Management Technician Baillie Karcher, the muslin bags were created in four standard sizes: one that took up the full width of the tray, one that took up half the width, one that took up one quarter of the width, and finally a long narrow bag for miser purses.

Soft beaded bags posed other difficulties. Because these bags lack structure, they tend to wiggle, creating creases any time they are moved. To prevent this, we inserted a one-fourth inch Ethafoam piece in each bag. Cutting the Ethafoam slightly smaller kept the insert from putting stress on the outer materials. Storing beaded objects in the muslin bags will keep loose beads contained should they become detached. Muslin fabric has a tooth, or a light grip, which further helps to keep the bag from moving in the tray.

Tray depths could be mixed and matched to go into each six-inch deep box. In this example, one 30 inch long box contains three two inch deep trays. Once the trays were filled and stacked in the boxes, a half inch sheet of Ethafoam was placed on top of the trays to keep objects from coming into contact with the lid. Each box in the collection has an exterior label listing its contents. Because of the quantity of objects within these boxes, we created a list specifying what could be found in each tray.

All of the accessories have been safely relocated to their new home, ready for museum programming and researchers. Seeing each individual piece during the inventory gave me a new appreciation for the depth and breadth of our collection. At the start of the accessory rehousing project, the accessories collection felt daunting to tackle due to its quantity and diversity. However, with the help of my colleagues on the Collections Management team, we safely and efficiently packed hundreds of years of costume history for future generations.