The work of supplying, healing, and feeding the population has always been essential. But the pandemic landscape has highlighted the fragility of the systems that sustain our daily life, reframing how we understand these professions. The expression essential work was one of the first new terms introduced to our lexicon since we began to shelter-in-place in March 2020. As we faced national shortages for the first time in recent memory, many people developed a greater appreciation for how supply chains work, what food symbolizes psychologically and emotionally, and which industries and individuals keep us alive.

In California we are especially sensitive to these issues—much of the essential work required to feed the country happens in our home state. Between 2017 and 2018, the California agricultural sector generated $50 billion. The state's 77,100 farms and approximately 420,000 farm workers cultivated one-third of the nation's vegetables and two-thirds of the nation's fruits and nuts. California's essential workers supplied school lunches, Sunday dinners, and midnight snacks not only across the United States, but also throughout the world; 41% of the industry's profits came from foreign exports.

LACMA's collection is filled with objects inspired by the rich history of essential work in California's agriculture industry. However, many of these objects celebrate California's bounty without recognizing the workers and systems responsible for creating it. By focusing on three groups of objects—fruit bowls, objects aligned with state boosterism, and activist-oriented graphic design—this blog seeks to recenter the histories of labor that have enabled the state's vast agricultural production.

Many of California's agricultural staples are ancient plants that have long delighted tastebuds and inspired art. Grapes, almonds, and citrus fruits are actually not native to this state, and were introduced at Spanish Christian missionary settlements following 1769. The Spanish missionaries originally obtained the plants—which are also not native to Spain—from longer histories of exchange with Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. When these fruits and nuts were "introduced" to California's landscape by European settlers, they were bound to the colonial project of land seizure. It is important to acknowledge here that LACMA is located on the unceded ancestral homelands of the Chumash and Tongva nations.

LACMA holds a multitude of objects designed to display and serve these agricultural products, which are today among California's most celebrated exports. For example, fruit bowls, like those designed by Georg Jensen (1918) and the Copper Shop of the Roycrofters (1915–20), once showcased grapes, fruits, and nuts as delicacies enshrined in silver. Historians cannot know if the Jensen and Roycrofters bowls would have been used to serve California-grown products on the foreign and domestic tables they decorated. However, it is true that these objects were created after California had established a nascent presence in the international food export market.

Elevating fruit above a table on hand-wrought pedestals, these objects are glittering trophies that once testified to their owners' abilities to procure rapidly expiring fresh fruit from distant places. But what is more impressive than the size of the former owners' wallets is the economy of California workers who grew, groomed, and moved fruits and nuts to 20th-century consumers' tables. As the refrigerated railroad car revolutionized the transport of fresh fruit around 1880, the construction and rail workers who built and subsequently maintained this infrastructure also played a major role in delivering fresh fruit to display bowls.

LACMA is also a repository of objects that advertise the agricultural bounty of California as a way of attracting investment to the state. For example, California orange crate labels made between 1877 and 1929 were typically decorated with romantic mission imagery. These designs aimed not only to sell oranges, but also to draw settlers, railroads, and irrigation investments to the still-expanding agricultural regions of the state. Printed after these preliminary goals had been realized, and corporate agribusiness thrived in cities like Riverside, LACMA's Red Circle orange crate label (c. 1938) moves away from the decorative tradition of nostalgic farm scenes. Instead, designer Dario De Julio deploys geometric minimalism to brand the "Red Circle" orange as a sophisticated and modern fruit. This eye-catching label was specifically designed to compete for the attention of buyers in a booming wholesale market for California produce. The industry had become so large that farmers relied on growers cooperatives to regulate the sale of produce. Red Circle was actually the McDermont Fruit Company's third and lowest grade of orange (the highest quality "Sunkist" oranges were marketed under the "Blue Circle," label, while the middle-tier oranges were sold under "Green Circle").

In the 1930s, industrial citrus producers like the McDermont Fruit Company relied on a large workforce of poorly compensated farmworkers. California farmworkers battled corporate union-busting tactics in their efforts to advocate for fair wages and humane treatment across the state, but finally made significant gains following massive strikes in 1933 and 1934. Despite this, California farmworkers were subsequently left out of New Deal legislation that improved conditions for industrial workers but ignored people employed in rural industrial agriculture.

Produce continued to be a symbol of lush life in the golden state into the 1960s, as can be seen on a set of woman's coordinates (1960) composed of an interchangeable blouse, dress, pants, and scarf and created by the California-based designer Irene Saltern. When wearing the pieces in Saltern's coordinates, wearers personify the state's harvest and dress in the uniform of its harvesters who wore scarves to cover their head and neck from the sun and trousers for ease of farming.

Finally, LACMA has collected many objects that wrestle with the reality that many of the agricultural industry's essential workers are underpaid, undervalued, and vulnerable in high-risk jobs. Paul Martinez's Cesar's Memory (1993) is an homage to César Chávez made at Self Help Graphics, a community-based print workshop and art center in Los Angeles. The text "No Grapes" references the United Farm Workers (UFW) Delano Grape Strike and Boycott of 1965–70, reminding viewers of the plight of California farmworkers as well as the power of collective action. In 1965, Larry Itliong and César Chávez led the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC)—a predominantly Filipino union—and the majority-Latinx National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) to walk off their jobs at Delano vineyards. The coalition of striking workers demanded a fixed wage for their labor ($1.40 an hour, 25 cents a box) and the right to form a union. In 1966, the two unions formally merged to become the UFW, and the strikers began to call for a consumer boycott of grapes, first from Delano and eventually, from all of California. The strike and boycott ended in 1970 after grape growers agreed to meet workers' demands. This victory fundamentally energized the U.S. labor movement, and Chávez continued to champion farmworkers and fight wage theft, unsafe conditions, and employer retaliation until his death.

The poster's many symbols, including the UFW logo and the Brahma bull, allude to Chavez's legacy. Additionally, the repetition of mirrored portraits of Chávez and falling typography convey a sense of movement—their composition evokes the banners and noises one might experience at a protest.

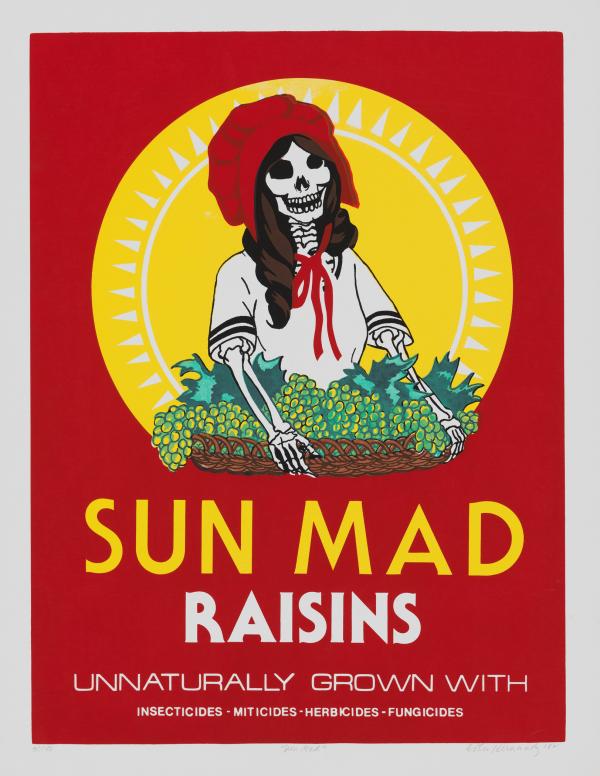

Ester Hernández was similarly motivated by the history of farmwork, both in her family and in her hometown in the San Joaquin Valley. Hernández's poster Sun Mad (1982) transforms the radiant Sun Maid icon into a radioactive calavera poisoned by "insecticides, miticides, herbicides, fungicides." The skeleton grins as she carries out her work for the global raisin distributer—which is based in the San Joaquin Valley—hauling an overflowing basket of ripe grapes. Ironically, her labor brings grapes to life at the cost of her own vitality.

Essential California farmworkers have continued to feed the country during the dual crises of Covid-19 and wildfire season. LACMA's collection reminds us to not only appreciate our food, but also remember where it comes from.

Thank you to all of the essential agricultural workers who are keeping us alive today, and to the longer history of California's essential workers who fought for our rights while feeding generations past.

Please join us for the final virtual panel in our "Racism is a Public Health Issue" series, "Essentially Forgotten: How COVID-19 Impacts Frontline Workers," on Tuesday, September 8 at 4 pm. The event will take place online via Zoom.

Resources consulted:

Borg, Axel. "A Short History on Wine Making in California." UC Davis Library Blog, July 5, 2016. https://www.library.ucdavis.edu/news/short-history-wine-making-california/.

Bronfenbrenner, K. (1990). California farmworkers' strikes of 1933 [Electronic version]. Retrieved May 28, 2020, from Cornell University, ILR School site: http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/articles/554/.

California Department of Food and Agriculture. "California Agricultural Statistics Review, 2017-2018." California Agricultural Statistics Review, 2017-2018. https://www.cdfa.ca.gov/statistics/PDFs/2017-18AgReport.pdf

California Department of Food and Agriculture. "California Agricultural Exports, 2017-2018." California Agricultural Statistics Review, 2017-2018. https://www.cdfa.ca.gov/statistics/PDFs/2017-18AgExports.pdf

Castillo, Andrea. "Farmworkers Face Coronavirus Risk: 'You Can't Pick Strawberries over Zoom'." Los Angeles Times, April 1, 2020.

Dunne, John Gregory, Ted Streshinsky, and Ilan Stavans. Delano: The Story of the California Grape Strike. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

Geisseler, Daniel and William R. Horwath, "Citrus Production in California." For Assessment of Plant Fertility and Fertilizer Requirements for Agricultural Crops in California, June 2016. https://apps1.cdfa.ca.gov/FertilizerResearch/docs/Citrus_Production_CA.pdf

Heidenreich, Linda. "Grounds for Dreaming: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the California Farmworker Movement." Agricultural History 90, no. 3 (Summer, 2016): 408-409. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1814320239?accountid=15172.

Linda L. Ivey. "Ethnicity in the Land: Lost Stories in California Agriculture." Agricultural History 81, no. 1 (2007): 98-124. Accessed June 24, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/4617802.

Kaiser Family Foundation. "Coronavirus (Covid-19) Outbreak Glossary." https://www.kff.org/glossary/covid-19-outbreak-glossary/.

Khasmanyan, Mari. "Guide to the Self Help Graphics and Art Archives Cema 3." Online Archive of California, https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt096nc9xv/entire_text/.

Knight, Henry. "Savage Desert, American Garden: Citrus Labels and the Selling of California, 1877-1929." U.S. Studies Online: The BAAS Postgraduate Journal, no. 12 (Spring 2008).

Olmstead, Alan L. and Paul W. Rhode, "A History of California Agriculture." Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics at University of California; University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, December 2017. https://s.giannini.ucop.edu/uploads/giannini_public/19/41/194166a6-cfde-...

Orr, Robert W. "The Creative Marketing of Lower-Grade Fruit by the California Citrus Industry from 1890-1955." Order No. 1525506, California State University, Dominguez Hills, 2014. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1539543682?accountid=15172.

Purdum, Todd S. "National Origins: California's Central Valley; Where the Mountains Are Almonds." New York Times, Sept. 6, 2000.

Stein, Walter J. Pacific Historical Review 52, no. 3 (1983): 327-28. Accessed May 28, 2020. doi:10.2307/3639019.