Chairs are the quintessential design object. They have a long history across place and cultures and are a captivating—and utilitarian—sign of the changing times. As part of the Latin American Art department’s design initiative, we have been steadily acquiring chairs and other types of seats over the last few years that show the breadth and variety of ways in which artists and designers have imagined and reimagined the simple seat.

In 2017 we interviewed the late Argentinean designer Ricardo Blanco (1940–2017) after acquiring his one-of-a-kind acrylic Plaka Chair (Silla Plaka), a folding chair cut from a single sheet of plastic. The chair derives from his 1972 laminated wood prototype that became an immediate hit due to its simple design, modern materials, and portability. Still in production today, the chair remains an icon of modern Argentinean design and is ubiquitous throughout the country. In 1977 Blanco reimagined his seminal design after he was invited by the Paolini plastics firm to participate in their annual salon. (The Paolini firm was founded in 1964 and by the end of that year, the first sheet of Paolini acrylic appeared on the market.) In 1970, Paolini began hosting competitions of “useful and useless objects” to assist artists and designers in their investigations of acrylic as a modern artistic medium, including Gyula Kosice (1924–2016) and Rogelio Polesello (1939–2014). This is Blanco’s only chair in this material, which the artist kept with him throughout his life until it was acquired by LACMA.

Many modern designers have turned to traditional forms to inspire their own seats. William Spratling (1900–1967) was born in the United States and made his career in Mexico, where he became a famed designer. In 1931 he opened a silver workshop and crafts studio, the Taller de Las Delicias, in Taxco. He was one of the first designers to revive the butaca, a type of ranch-style easy chair with distinctive crossed supports, made of local wood. Thought to have originated in the Caribbean, the butaca’s overall shape and low height probably derive from pre-Columbian ritual seats, while its rigid forms, materials, complex wood joinery, and iron nails are influenced by Spanish state folding chairs known as sillas de caderas, which arrived in the New World with early settlers. In Mexico, the butaca became popular as a resting chair confined to private spaces and used for informal occasions. Aside from Spratling, other modern designers working in Mexico also revisited the popular chair form in the 1930s through the 1960s, including Don Shoemaker (1919–1990) and Josef Albers (1888–1976).

Michael van Beuren’s “San Miguelito” Chair offers yet another modern reinterpretation of the butaca that uses Mexican white pine wood (ayacahuite) and natural fibers such as woven agave fiber (ixtle). Van Beuren was an important catalyst in the introduction of modern furniture design in Mexico in the 1930s and 1940s. Born in New York, he moved to Europe in 1930 to escape the Great Depression, and, along with several other Americans, attended the legendary Bauhaus art school in Dessau, Germany, from 1931–32. After the outbreak of World War II, Van Beuren moved to Mexico, where he began designing furniture. Along with German Klaus Grabe, who was also Bauhaus educated and arrived in Mexico a few months after him, he founded the small furniture label Domus. The “San Miguelito” Chair is representative of the company’s high-quality furniture that combined Mexican materials and craftsmanship with a more modern, streamlined aesthetic that reflected a Bauhaus sensibility of radically simple forms, rationality, and functionality.

Brazil was another important hub for mid-20th century design that integrated local materials and modern furnishings. The Rio Chaise is one of the most important furniture designs by Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer (1907–2012). Early in his career, Niemeyer worked as a draftsman for Le Corbusier (1887–1965) in Rio de Janeiro. His most emblematic project of the 1950s was Brasília, which represented the ultimate rebuttal of functionalism in favor of a more ductile and organic approach to architecture. Niemeyer spoke of preferring free-flowing, sensual curves, which he found more organic, over the straight and inflexible angles and lines typically found in human-made objects. This chair was designed in collaboration with his daughter Anna Maria Niemeyer (1929–2012) during their years in Paris. The combination of materials—plywood, cane, and leather—is masterfully balanced to provide a functional and sculptural form that does not overpower the space around it—a major concern for Niemeyer. With its interplay between solid elements and empty areas, the voluptuous chair resembles a drawing in space.

In 1942 Niemeyer commissioned Joaquim Tenreiro (1906–1992) to design the furniture for a home he was building in Minas Gerais, in southeastern Brazil. Tenreiro himself soon emerged as a leader of Brazilian design. His work combines a modernist aesthetic with Brazil’s natural materials—especially its tropical woods. Designed in 1947, Three-Legged Chair embodies Tenreiro’s sleek and timeless aesthetic. The sensuous lines of the chair highlight the interplay between light and dark woods. Stacked and joined together, the two woods are not only decorative elements but are part of the structural design of the work, demonstrating Tenreiro’s masterful understanding of the properties of his material.

Italian-born Achillina (Lina) Bo Bardi (1914–1992) moved to Brazil in 1946 and made a name for herself as a designer and architect. She is well known as the architect of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo, but also designed private homes including her own Glass House in the Morumbi subdivision of São Paulo and one for her friend Valéria Cirell (1958). Bo Bardi created this deckchair especially for the Cirell House (a project that combined rigid geometry with organic references to nature) and its verandas that offered a pleasant place to lounge. The removable leather sling on a modernist iron frame related to Bo Bardi’s earlier designs, which drew inspiration from the hammocks used on Brazilian riverboats.

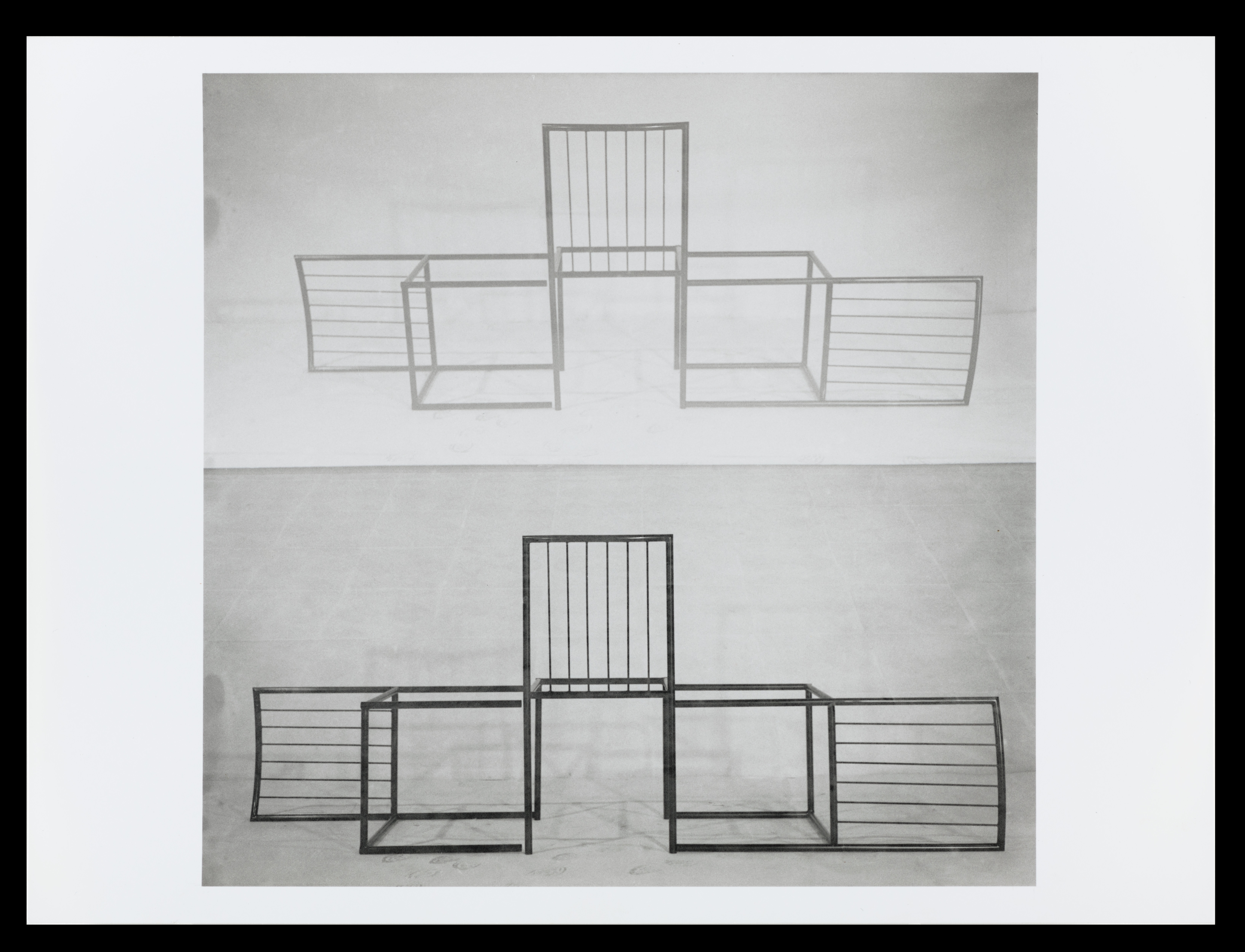

Geraldo de Barros (1923–1998) was a pioneer of Brazilian concrete art, photography, and design. In 1951 he received a fellowship to travel to Europe, where he met the Swiss artist, architect, and designer Max Bill (1908–1994), whose teachings proved foundational for the formation of his own ideas of concrete art and design. In 1954, he co-founded Unilabor, a utopian cooperative on the outskirts of São Paulo, which aimed to create modern furniture designs at affordable prices. Many of these works combined industrial materials, such as iron and plywood, with lush tropical woods. LACMA previously acquired a shelving unit that de Barros designed for Unilabor, and recently added a set of his iconic Unilabor chairs. In addition, we acquired a number of de Barros' photographs of his signature chairs that highlight their geometric and sculptural qualities.

We look forward to presenting many of these new acquisitions in LACMA’s new building, and until then: have a seat! Think about the different types of chairs and seats you encounter in your everyday life.

Further Reading

Barros, Fabiana de, ed. Geraldo de Barros: Isso. São Paulo: SESC São Paulo, 2013.

Blanco, Ricardo. Ricardo Blanco: Diseñador. Buenos Aires: Editorial Franz Viegener, 2015.

Cals, Soraia, ed. Tenreiro. Rio de Janeiro: Bolsa de Arte do Rio de Janeiro, 1998.

Lima, Zeuler R.M. de A. Lina Bo Bardi. Foreword by Barry Bergdoll. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

Mallet, Ana Elena. Bauhaus and Modern Mexico: Design by Van Beuren. Mexico City: Arquine, 2014.

Morrill, Penny C., ed. William Spratling and the Mexican Silver Renaissance. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., in association with the San Antonio Museum of Art, 2002.

Philippou, Styliane. Oscar Niemeyer: Curves of Irreverence. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

For more on the history of the butaca, see Carlos F. Duarte’s entry in Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800, edited by Ilona Katzew, cat. no. 91. Exh. cat. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and New York: DelMonico Books 2022.