There is a long tradition of writing based on works of art, known as ekphrastic writing. A deep and rich dialogue emerges from this mixture of observation, personal interpretation, and creativity.

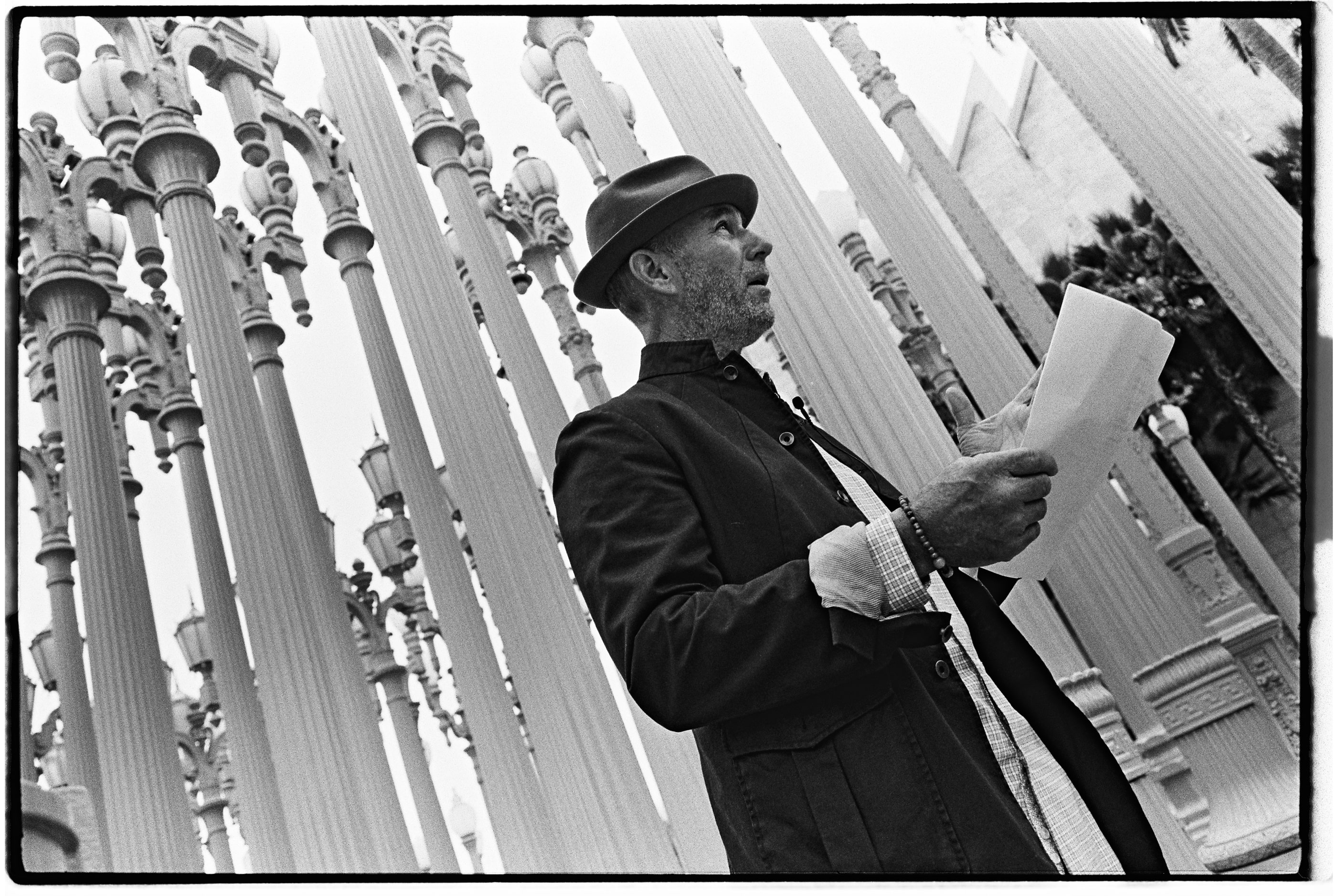

Italian poet and writer Gabriele Tinti has an ongoing reading series inspired by ancient and modern myths. For some time, Tinti has hoped his ekphrastic poetry project could engage with LACMA’s collection. Earlier this summer, Tinti, actor Jamie McShane, and a small group of videographers filmed McShane reading Tinti’s poem responding to Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s Apollo and Phaëthon (c. 1731).

In LACMA’s publication Gifts of European Art from the Ahmanson Foundation, Vol. 1, we learn about this ancient myth and Tiepolo’s painting:

The story of Phaeton opens the second book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Phaeton, ascending to Phoebus Apollo’s palace in Olympus, implores the god to confirm that he is his son by the Oceanid Clymene. Apollo, acknowledging his paternity, offers his son a favor of his choice. Phaeton then requests permission to drive the chariot his father leads across the zodiac to bring in each new day. However, unable to control its horses. Phaeton causes the chariot he is driving to plunge close to the earth, scorching its surface and creating the deserts of Africa. Alarmed, Jupiter puts an end to the near disaster by striking the chariot with his thunderbolt.

The fall of Phaeton from his chariot was often represented like the Fall of Icarus because it also stood as an image of hubris. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, however, following Ovid’s text almost to the letter, chose to illustrate the moment when the son points out to his father the rearing horses of Apollo’s chariot.

In advance of the premiere of the video recording, LACMA asked Tinti a few questions about his inspiration and process.

What was compelling to you about this painting?

Gabriele Tinti: The way Tiepolo depicted Phaethon’s impossible appeal to his father Apollo. In the painting, the god—at the summit of a magnificent, lyrical foreshortening, symbolizing the ineffable—really does seem to shrink from Phaethon’s request (non honor est: poenam, “is not honor but condemnation”) while Phaethon is captured in his insistent demand, in wanting at all costs “to sin,” prefiguring the “sin” of Thomas: having to touch in order to believe.

Tell us about your partnership with actor Jamie McShane. How did you two come to collaborate on this project?

Gabriele: I met Jamie McShane through a close mutual friend, Vincent Piazza, who put us in touch many years ago. Jamie is an actor usually engaged in giving body and voice to antagonists, to outsiders. We had long been talking about working together and came together on this idea: to give voice to Phaethon, to this tormented, inquisitive, unresolved, courageous man who—as the Naiads wrote on his tomb—magnis excidit ausis, “died daring a great deed”.

Can you share a bit about your interest in writing poetry that responds to paintings and sculptures?

Gabriele: Lessing asserted that poetry should “keep to the laws of physical painting” as Homer did, when he “pictorially” described Achilles’ shield in a “painting” of more than a hundred lines “thanks to which he has been considered a master of painting since antiquity.” This mixing, this coexistence of the arts in a single creative space, which Lessing takes to a paradoxical outcome by calling Homer a “painter” and his poetic work “painting”, is something original that is consummated in Horace’s principle of the ut pictura poesis: painting as silent poetry and poetry as speaking picture. Now, as then, the writer cannot do without images, just as the painter cannot do without words.

What do you hope audiences will take away from this video?

Gabriele: I would like them to go back and look at myth as a generative force, a participating and creative dimension of the present and not only of a remote past that no longer exists.

Unfortunately, academic studies have reduced ékphrasis to a descriptive style, to a didactic genre of writing, while in antiquity the term indicated the performance of the bard for the participation (mimesis) of an audience that listened and responded. Poetry was ritual. Today all this seems lost. The real meaning of ékphrasis—ek (outside) phrazein (to show)—that of taking out, showing and nearing an image to the listener/reader, though, remains. I like to think it is possible to enter the rooms of a museum and shake the works (the myths that these represent) out of the torpor in which we have confined them. The public can still be called on to pause, to pay attention, to make some response.

The video of actor Jamie McShane reading Gabriele Tinti’s poem premieres on YouTube on Monday, August 15 at 4 pm. You can RSVP to receive a reminder email in advance of the premiere, or watch the video anytime afterwards.