Reflecting on the 1920s, when he came to prominence as a film director, Fritz Lang said: “Perhaps never before was there a time that sought new forms through which to express itself with such reckless determination.” Thus Lang characterized the zeitgeist of the Weimar Republic, a fragile liberal democracy that replaced the kaiser’s imperial government in 1919 and ended with the rise of National Socialism in 1933. During this tumultuous period, culture flourished amid social unrest, inflation, and excess.

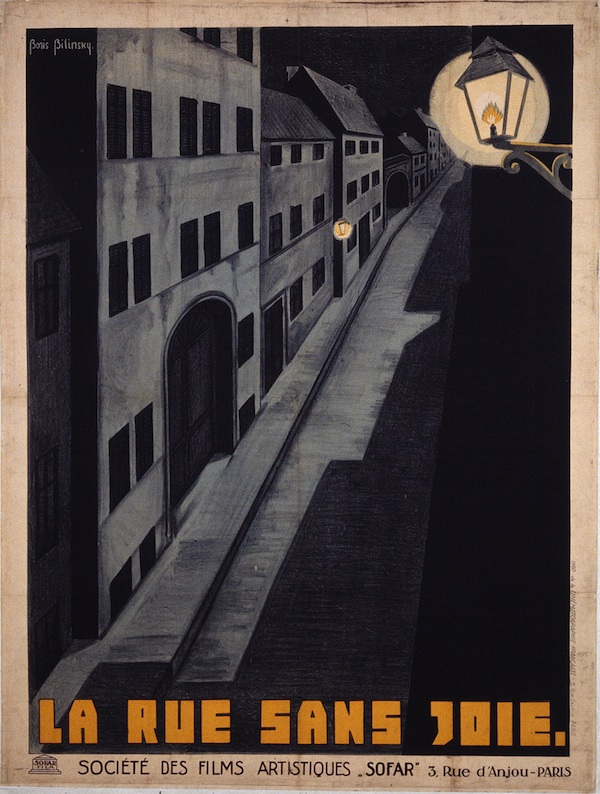

In this exhibition, clip sequences reveal the guiding vision of directors such as Lang, F. W. Murnau, G. W. Pabst, and Robert Wiene. Working drawings and vintage photographs document the skill of the architects and designers with whom they collaborated; vintage posters hint at the omnipresence

of film culture on city streets. These unique materials survive thanks to the efforts of Lotte Eisner, a German film historian who immigrated to Paris in 1933 and over time persuaded many of her former compatriots to donate their archives to La Cinémathèque française. Eisner also inspired the title of LACMA’s exhibition; her pioneering 1952 book, The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt, compiles her reflections on Expressionism’s theatrical origins, her critical evaluations

of key films and directors, and her theories about German cinema in relation to national character.

Film brilliantly registered the Weimar era’s anxiety and exhilaration. Inspired by the new art form’s potential, a cadre of talented directors, production designers, architects, cinematographers, writers, and actors forged the cinematic style known as Expressionism. Rebellious, antirealist, and reliant on exaggerated gestures and primal emotions, Expressionism had emerged in German art, literature, and theater in the years preceding World War I. As seen in the recent LACMA exhibition Expressionism in Germany and France: From Van Gogh to Kandinsky, the style had complex origins and exerted a widespread influence, only to be interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. Expressionism resurfaced in silent cinema in the 1920s, mirroring the strains of modernization and distinguishing German film in the international marketplace.

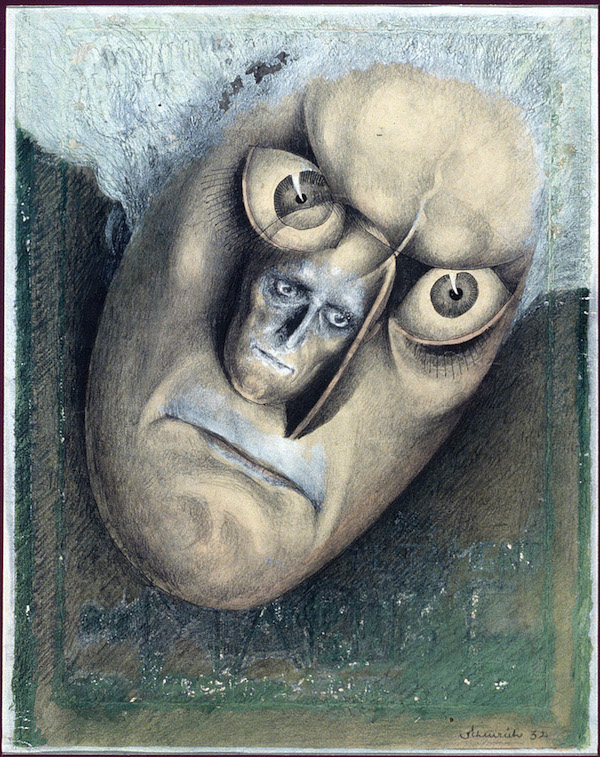

Expressionism’s visual hallmarks—chiaroscuro lighting, elaborately fabricated sets, angular graphics—produce a mood of yearning, unease, and paranoia. While often manifesting itself with genuine anguish, the style could also be mocked by its very creators. In Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922), the evil protagonist is asked his opinion of the phenomenon. “Expressionism?” scoffs Dr. Mabuse. “It’s just a game. Everything is a game nowadays.” This cynicism is part of the complex emotional maelstrom of Expressionist cinema. Plots are equally complex skeins of flashbacks, dream sequences, and reversals. Characters such as magicians, doppelgängers, automata, vamps, clowns, princes, devils, bureaucrats, and killers embody the murky ambiguities of human identity.

Visitors to Haunted Screens will see that the plaza-level galleries of LACMA’s Art of the Americas Building have been transformed yet again into a stylized, abstracted landscape. The design team, jointly led by Amy Murphy and Michael Maltzan with Michael Maltzan Architecture, Inc., readily embraced the challenge of creating a framework for these historic objects and images. As they put it, “One of the most compelling aspects of German Expressionist cinema is the works’ use of dramatic spatial sequences as an inherent part of storytelling. Without trying to mimic the iconic aesthetic of this movement, we looked instead to provide visitors with a way to engage the spirit of the works through a contemporary series of forms and spaces. The exhibition’s architectural elements intentionally create an undulating dialogue between dark and light, inside and outside, space and form, rupture and unity—highlighting the simultaneous and often overlapping worlds of art, film, and design so often represented within each film’s production.”

The interior areas, or tunnels, contain suspended screens, on which clips are projected. Set design drawings, still photographs, and other works on paper are presented on custom-designed shelves and columns, their unorthodox presentation emphasizing their status as working documents, in service of the final films. The exhibition’s roughly chronological sequence also highlights the thematic preoccupations and increasing technical resources of Expressionism’s key directors. The first section, “Madness and Magic,” focuses on a psychological and societal tendency to turn inward and escape into the imagination. Making do with limited resources in the early years of the Weimar period, directors developed innovative means of exploring complex themes in the cinematic medium.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) embeds text within the live action and features an unforgettable hand-painted, anti-illusionistic set design. Just as the visual environments in Expressionist films are off kilter, so are the characters unhinged: a clay figure comes to life in The Golem (1920); a doctor may be a charlatan or a killer in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari; a law student turns murderer in Crime and Punishment (1923). With their multiple identities, these equivocal protagonists must have struck a chord for audiences unsure about the individual’s role in a new society.

Identity could also be sought in the past, as explored in the exhibition’s second section, “Myths and Legends.” Many postwar artists looked back to German Romanticism at the turn of the nineteenth century, with its visionary heroes and exaltation of nature. Harking back to classic tales, films such as Fritz Lang’s Nibelungen (1924) helped German audiences transcend postwar privation and bolstered their sense of national identity. Epic tales required bigger productions, many of them funded by the leading studio, Universum Film AG (UFA), under the producer Erich Pommer. As the economy began to recover and German films proved their viability on the international market, Pommer sought to rival the scale of Hollywood. Lang’s ambitious two-part Nibelungen took an unprecedented nine months to film and earned acclaim for its artistry. F. W. Murnau’s Faust (1926) likewise reveals painterly influences; the cinematographer Carl Hoffmann emulated the Romantic technique of Stimmung, or the play of light and shadow, with novel special effects.

While many Expressionist films transported audiences to faraway or imaginary places and times, others were rooted in present-day urban reality, as demonstrated in the third section, “Cities and Streets.” The growth of German cities during the Weimar period—the population of Berlin rose to 4.24 million, making it the world’s third-largest metropolis after New York and London—led to housing shortages, unemployment, strikes, and demonstrations. Industry and technology also transformed everyday experiences for the urban populace. Cities teemed with automobiles, streetcars, advertising, and pedestrians. The resultant sensory overload, anxiety, and alienation could be captured on film via composition, editing, and—beginning in 1927—sound.

Haunted Screens concludes with a section called “Machines and Murderers.” As the 1920s unfolded, the stylization and subjectivity of the earliest Expressionist films gave way to an approach known as New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), a movement that will be examined in greater depth in a forthcoming LACMA exhibition, New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic, 1919–1933, opening in October 2015. Despite its nominal realism, the new style was nonetheless reliant on special effects and production design and could be applied to any story line, from futuristic fantasy to present-day murder mystery, as Fritz Lang demonstrated in three masterful films: Metropolis (1927), M (1931), and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933).

If these films offer warnings about Germany’s political situation in the late 1920s and early 1930s, none of them explicitly show the Weimar Republic being dismantled by the National Socialists, with their repressive and anti-Semitic policies. Lang, along with many of the directors and artists whose work is featured in this exhibition, was forced to emigrate in 1933. Mass exile brought an end to Expressionist cinema in Germany while facilitating its dissemination and evolution worldwide; this significant historical development is explored in the concurrent exhibition at the Skirball, Light and Noir: Exiles and Émigrés in Hollywood, 1933–1950. While only a small percentage of the approximately three thousand films produced in Germany during the Weimar Republic can be considered Expressionist, the style proved decisive for thefuture evolution of cinema, helping to establish its artistic and psychological potential, advancing camera technology and special effects, and giving rise to genres such as film noir, science fiction, and horror.

A version of this article originally appeared in the fall 2014(volume 8, issue 4) of LACMA’s Insider.