This week, as part of the museum’s 50th anniversary, we unveiled our new casta painting by Miguel Cabrera, one of the most acclaimed painters of 18th-century New Spain (Mexico). Between 1750 and his death in 1768, Cabrera painted hundreds of canvases. He was the favorite painter of the Society of Jesus and also received commissions from virtually every other religious order as well as numerous members of the elite. Cabrera was also president of an academy of painting established in Mexico City in 1754, which gathered some of the best painters of the day and aimed to elevate the status of painting in the viceroyalty.

In 1763 Cabrera created his famous (and only known) set of casta paintings, a uniquely Mexican pictorial genre documenting the process of racial mixing among the colony’s inhabitants: Amerindians, Spaniards, and Africans. Largely hailed as one of the best of the genre, Cabrera’s set originally comprised 16 separate canvases: eight paintings are now in the Museo de América, Madrid; five are in a private collection in Monterrey (Mexico); and one is in the MultiCultural Music and Art Foundation of Northridge, California. LACMA’s picture is one of two works whose whereabouts had remained unknown, which makes its discovery thrilling.

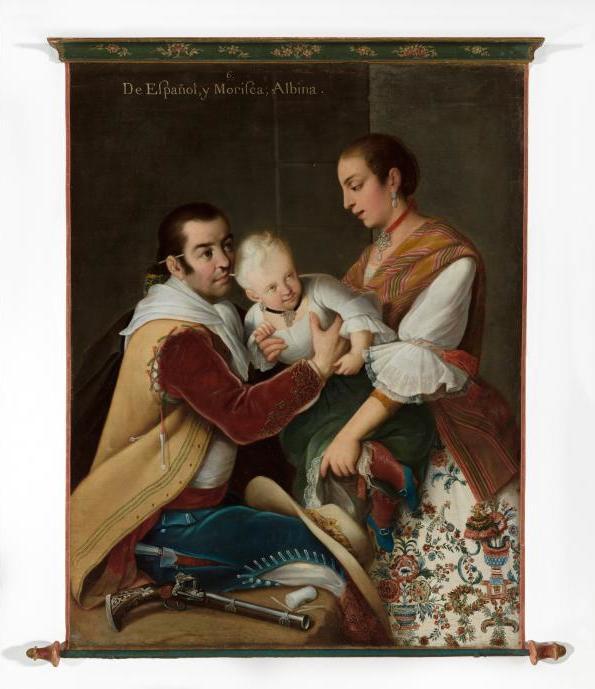

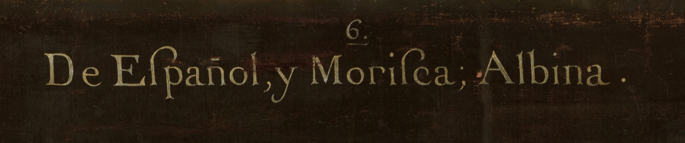

As noted in the inscription, the picture portrays the mixture of Spanish male and a morisca woman who beget an albino child.

The tenderness of the scene, with the morisca woman gently handing over her child to the Spanish man, is striking, as is the attention lavished on the figures’ clothing, a combination of New Spanish, European, and Asian garments. The morisca woman wears an ornate calico skirt with floral motifs and an elegant Mexican rebozo (shawl) over a European-style blouse with elaborate lace cuffs. A tassel dangles over her richly patterned skirt, creating a striking trompe l’oeil effect. Both the woman and child wear sumptuous chokers and earrings made of precious stones.

The Spanish man is depicted wearing a leather coat with attached red sleeves of the type worn by a special group of soldiers known as dragones de cuera, after their protective leather coat. He is shown next to a silver-inlay Spanish gun known as a trabuco (typical of those made in the town of Ripoll, Catalonia) with a knife secreted in his trousers. A broad leather hat rests on his knees. The dragones de cuera were charged with colonizing rebellious Indians in the Sierra Gorda and northern frontiers of the viceroyalty.

Aside from the Spaniard’s markers of class and occupation, he is shown smoking (note the second cigarette behind his ear), with a package of cigarettes near at hand. (Tobacco, a staple of the New World, yielded great revenue to the Spanish crown.)

During the colonial period, Indians, Spaniards born in Spain as well as in the New World (the later known as Creoles), and Africans, all populated Mexico. As a result, a large percentage of the colonial population became mixed; these racial mixes were known collectively as castas (or “castes” in English)—from where the pictorial genre derives its name. Casta paintings were produced largely for a European audience to classify and create order of an increasingly mixed society. This was especially important because there existed in Europe the widespread idea that all the inhabitants of the Americas (regardless of race) were degraded hybrids, which cast into doubt the purity of Spaniards’ blood and their ability to rule the colony’s subjects.

One question that I frequently get asked is, why does the picture depict an albino girl? The answer is not simple, but I will offer some broad thoughts (I delve into the subject in more depth in the volume Envisioning Others: Race, Color and the Visual in Iberia and Latin America, edited by Pamela Patton, forthcoming with Brill).

In the 18th century (and before), the birth of albino people was amply debated. Albinos were sometimes seen as monstrous races—anomalies that bore no resemblance to their progenitors—and were frequently collected and paraded in Europe as human curiosities. Even the Aztec emperor Moctezuma is said to have collected albino people along with rare specimens of birds and animals in his famous zoo.

Though today albinism (a disorder and not a disease) is widely known to be caused by a genetic mutation that impedes the body from producing or distributing pigmentation, 18th-century science could not entirely account for the birth of albinos, and a whole array of bizarre conjectures were advanced to explain their “whiter than white” coloration.

One theory, for example, argued that albinos could only be born from darker parents, essentially people of African descent. And Cabrera’s picture (as well as numerous other casta paintings) echoes this theory: the morisca mother is the progeny of a Spaniard and mulatto woman, who in turn is the offspring of a Spaniard and black person.

Some theories even argued that albinos proved that darker bodies could revert to whiter ones without having to mix with Europeans (or “whites”). This was important because certain commentators believed that the original color of humankind was white and that the birth of albinos proved humanity’s propensity to return their so-called original whiteness (associated with “purity”).

Casta paintings, including Cabrera’s picture, connect albinism with black ancestry. The painting illustrated above, for instance, depicts the mixture of a Spanish man and an albino woman. The child has receded in the racial pole and is represented with dark skin. The painting’s inscription renders the child’s regression clear: she is labeled a torna atrás (literally, “return backwards”).

The need to emphasize the black origin of albinos reflects European and creole anxieties over the instability of skin color and the concomitant blurring of racial boundaries that could undermine their ability to rule—including implicit fears relating to the legitimacy of the slave trade. Casta painting responds to this anxiety by constructing a view of an orderly and mixed society bound by love (hence the use of the familial metaphor), one that was hierarchically arranged and always featured Spaniards at the top. The images also picture the New World as a land of boundless natural wonder through precise renderings of native products, flora, and fauna.

As I have argued elsewhere (see references below), casta paintings are fascinating documents of the time that not only mirror but actively construct many notions of the period regarding colonial society—what emerges is a picture that is neither static nor consistent. But it is precisely this layering of meanings and the inherent tension between the textual component of casta paintings (underscoring the racial and hierarchical division of society) and the visual one (hinting at the abundance of the land) that make the genre so compelling.

Further Reading

Katzew, Ilona. Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004.

Katzew, Ilona, “White or Black? Albinism and Spotted Blacks in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World.” In Envisioning Others: Race, Color, and the Visual in Iberia and Latin America. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2016, pp. 142–86.