“I paint to save my life and to kill time.”

—Morris Graves

When I first began researching two early paintings by Morris Graves, Cat with Red Cabbage and Majestic Dog, both 1935, little did I know it would lead me on a quest that would culminate in the exhibition Morris Graves: The Nature of Things, now on view at LACMA. The journey has been eventful and replete with chance encounters, especially with fellow travelers along the trail Graves blazed—a surprisingly robust following of admirers, despite the scarcity of opportunities to see the artist’s work on view outside his native Pacific Northwest. This absence made me, and the other Graves’s fans I met along the way, wonder why such an exquisitely understated and quietly powerful body of work no longer seemed to be relevant to the narratives being told in museum displays these days. So it was thrilling for me to discover that Graves’s work continues to command an impressive audience and to resonate with the concerns of contemporary artists.

One of Graves’s contemporary admirers is Robyn O’Neil, a local L.A. artist. Initially, I imagined that our conversation would follow the standard form of an interview, but since Robyn’s practice encompasses writing, we decided on another approach: a loosely structured, informal exchange about Morris Graves, conducted here in the gallery at LACMA, followed by a text she would write.

I’m infinitely grateful to Robyn for her willingness to participate in this adventure. Not only was I curious about what drew artists today to Graves’s work, with which I was entirely smitten, but I also had a desire to share my enthusiasm beyond the confines of the modest gallery space at the back of the American Art department collection. And rather than retell the same story told on those walls, I offer Robyn’s perspective on Graves.

“What we need is more people who specialize in the impossible.”

—Theodore Roethke

MISUNDERSTANDING NATURE IN ART

The main wall of The Nature of Things contains three of Morris Graves’s drawings along with a display of an exquisite Japanese scroll. Two of the drawings are of loons, both of their heads arching upward. The ascension of gaze we see in these lone bird images summarizes so much of what we see in Graves’s images of the natural world—isolation paired with hope, one never without the other.

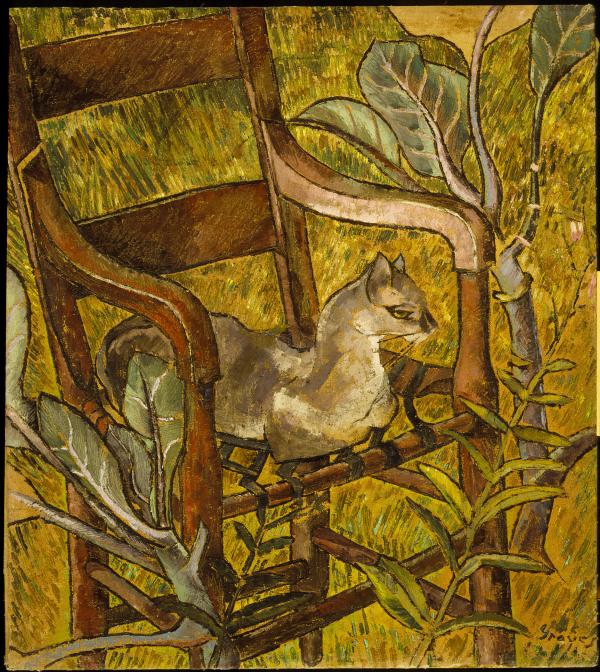

You see, Graves could be mistaken for an artist who simply celebrates nature through skillful renderings, and I take issue with that limited reading of his work. Remember, John James Audubon is another artist known for drawing/painting birds—and, proving that everything is more complex than it seems, Audubon killed all of the birds he illustrated. With Graves, these are beyond illustrative in that they’re meditations on existence, never ignoring the grit that comes along with it. Graves depicts nature and existence as it actually is—each moment achingly full of both tragedy and glory. But none of this is ever clear or pedantic. There’s a searching in his imagery.

SLOW/QUIET

These pieces are demanding in an underhanded way, in that they require a slow attention. One glance isn’t enough, and Graves lived a life that was dedicated to quiet. So it makes sense that his work requires a similar slow and careful spirit from us. There’s nothing huge, loud, or quick about the work of Graves, and that is what sets him apart from his contemporaries, not the region where he chose to live. (If I could do one thing in regard to Morris Graves, it would be to stop people from referring to him as a regional artist.)

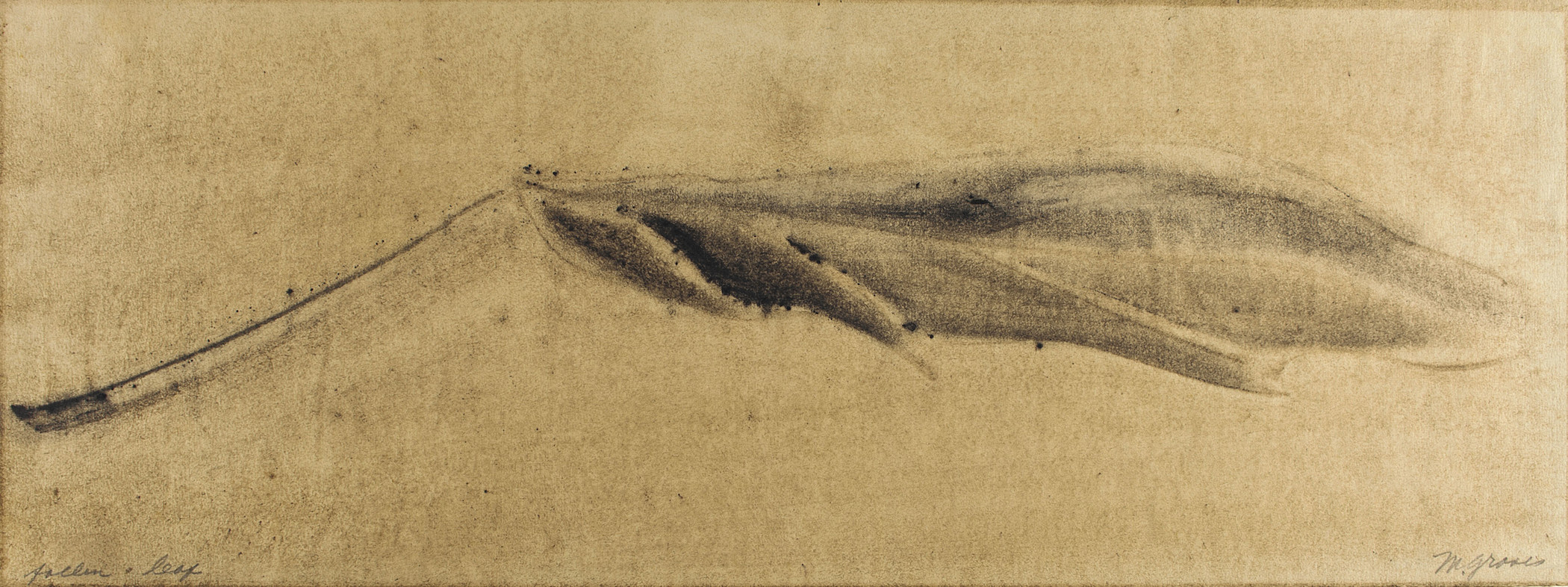

FALLEN LEAF

I gazed at Fallen Leaf from across the gallery for a good 30 minutes before approaching the drawing. Being that I didn’t yet know the title, I completely mistook the image for a mountainous landscape. Blur your eyes and you’ll see the same thing. It’s a brilliant duality Graves conjured in this piece, the delicacy of a solo fallen leaf and the quiet strength and foreverness of a mountainscape.

SLIPPAGES

Theodore Roethke, who for a time rented Graves’s home north of Seattle, said it best: “Those who are willing to be vulnerable move among mysteries.” As evidenced in every piece in this exhibition, Graves is a master at allowing mystery to imbue recognizable imagery. Even a leaf, which is as common and identifiable as it gets, becomes something of an abstraction with Graves. His imagery slips in and out of definition. This is one of many reasons his work is resonant. It’s remarkable that, though most of his work is an image of one thing by itself, his work never reads as simply a portrait of one particular thing. Stare at any of it long enough, and as you breathe in and out, the drawing will change as rapidly as your breath. A seemingly goofy/cartoony-looking bird face (as in Spirit Bird) is as murderous as it is humorous.

Morris Graves: The Nature of Things is on view in the Art of the Americas Building, Level 3, through July 4.