In October 1964 the 34-year-old Chilean artist Guillermo Núñez arrived in New York. Trained as both a painter and a stage designer, by the early 1960s Núñez had become more attuned to representations of violence and recent events further fueled his interest in this theme. Just two months earlier, U.S. Congress had signed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, giving President Lyndon B. Johnson authorization to use military force in Southeast Asia. The horrific images making their way out of Vietnam through television and print media wove themselves into Núñez’s work as the artist grappled with the war’s ongoing death and destruction. LACMA recently acquired two fascinating paintings from Núñez’s New York period, which are now on view in our Latin American galleries for the first time.

Both paintings date to 1965 and incorporate abstract forms that evoke bones, joints, and ribs. In this painting, white bodily forms and brushstrokes of blood red are set off against the dark background. The painting conjures a sense of violence, threat, and danger, without depicting a specific event. The abstractions of Núñez’s earlier work became increasingly populated with bone-like shapes during his months in New York in response to the images emanating from Vietnam. The war also gave rise to other unprecedented motifs in his paintings of this period.

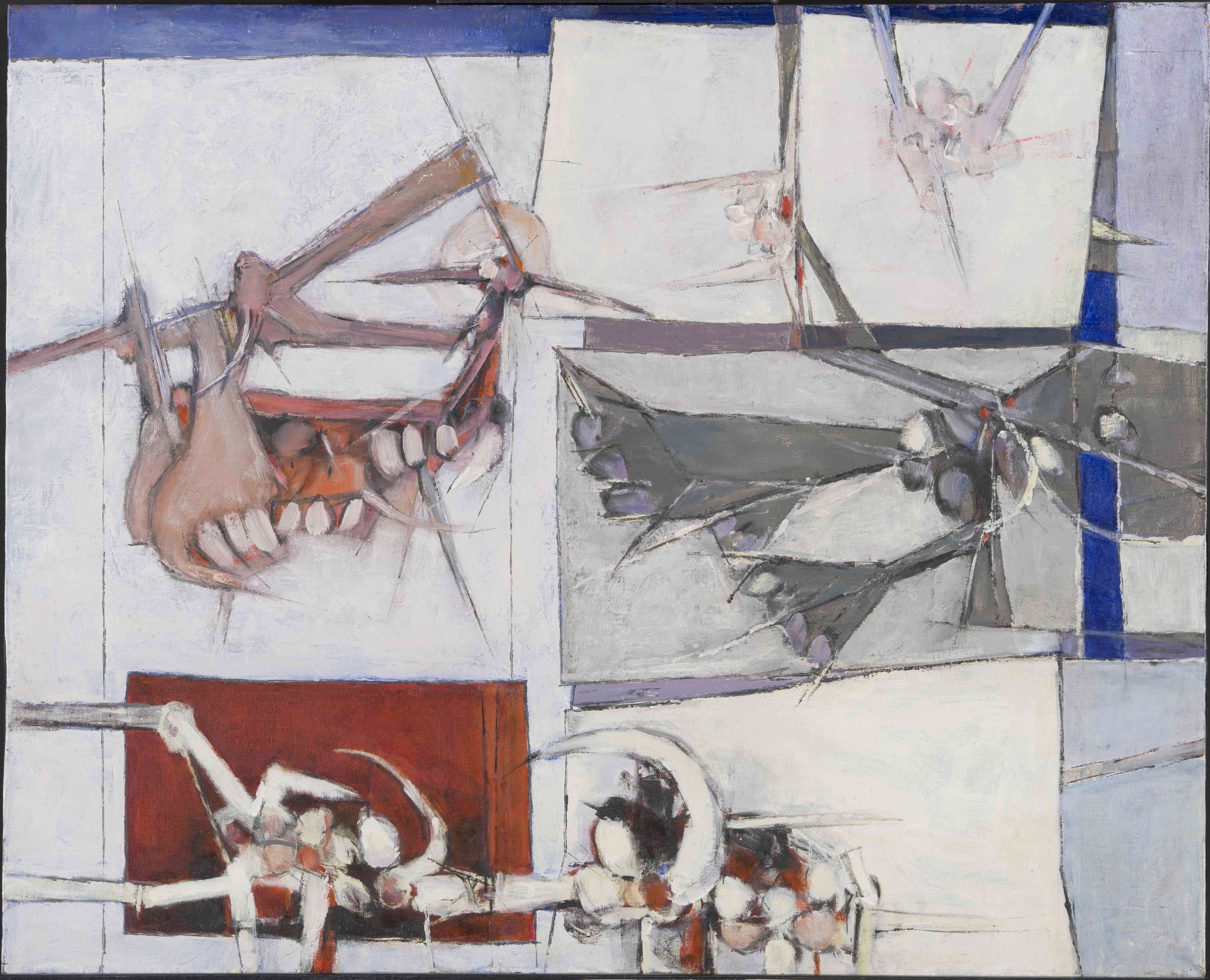

Here the pink propellers of a military helicopter are mashed up with a mangled mouth. Helicopters—used for support and evacuation as well as attack—saw greater use in Vietnam than in previous wars and became a ubiquitous symbol in the media. The triangular gray forms in the middle of the composition recall images of fighter planes and double as outstretched claws for a hybrid creature emerging from the right edge of the canvas. Núñez reinterprets his helicopters and aircrafts as part beast and part machine, heightening the terror they cause.

.jpg)

At LACMA these paintings join the work of fellow Chilean Roberto Matta (1911–2002), whom Núñez encountered in New York. There he also discovered Pop art and became interested in the movement’s fascination with popular imagery and mass media. The white rectangular forms that appear in the background of Untitled derive from an expressed interest in comic strips. In this painting, alternately known as Non Comic Strip, Núñez addresses the lack of humor in current events while employing the compositional devices of this familiar format. The artist returned to Chile in August 1965, where he continued to explore the comic strip frame and introduced silk-screen printing into his canvases, becoming a leading proponent of Pop art in his home country.

In March 1966 motive magazine published a statement by the artist on “Chilean Art and Art in the USA.” The official magazine of the Methodist Student Movement in the United States, motive received increasing attention in the 1960s for its strong progressive views, including its stance against the Vietnam War. As part of a feature on 11 Chilean painters, Núñez championed the potential of art as protest and criticized what he considered Pop’s lack of social engagement: “Viet Nam suffers daily bombings, and there many die. But nothing, nothing of this is present in the U.S. paintings! While the world threatens its end, the U.S. dances around its new idols, the Campbell Soups [sic] paintings.This is where I think U.S. art is false. It doesn’t start from the depth of real life, but from the surface which has no importance.”

In his own work Núñez drew on the visual strategies of Pop art to communicate his social criticisms and protests, creating what he would later call “arte pop-lítico,” or pop-litical art. During the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet—lasting from 1973 to 1990—Núñez’s politically engaged art led to his detainment, torture, and eventual exile in Paris in July 1975, where he spent the next 12 years. While this experience has largely shaped the interpretation of Núñez’s oeuvre, works from his lesser known New York period display the artist’s early interest in the social implications of violence. Now on view at LACMA in the context of works by Latin American artists from the 1960s, Núñez’s works provide a window into a volatile moment in history and international artist responses.

View Guillermo Núñez’s works in the Latin American art galleries in the Art of the Americas Building, Level 4.