One of the many themes in the current exhibition City of Cinema: Paris 1850–1907 is the 1889 Exposition Universelle, or World’s Fair, which took place May 5–October 31 of that year, the fourth of eight such expositions to be held in Paris between 1855 and 1937. The 1889 fair attracted over 32 million visitors during its almost six-month-long run and this specific exposition is epitomized for eternity by Gustave Eiffel’s triumphant creation, the eponymous Eiffel Tower—which would become the most recognizable symbol of Paris forever after it was erected for the fair.

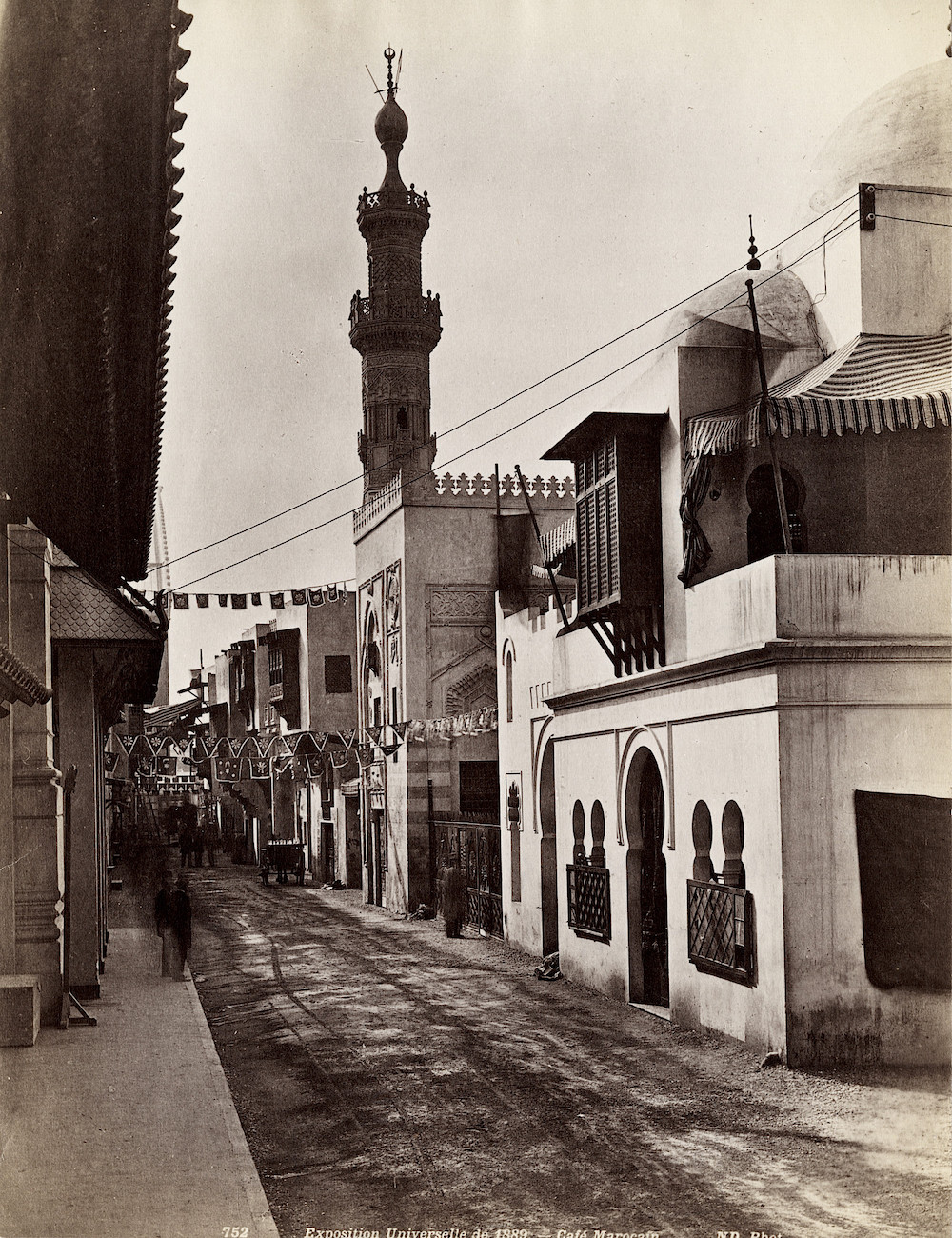

Although the Eiffel Tower remains an ubiquitous symbol for Paris and France to this day, the second most popular attraction at the 1889 Exposition Universelle was the Rue du Caire, or “Street of Cairo.” The street was fabricated and later dismantled (the same fate had originally been planned for the Eiffel Tower itself!) and this manufactured environment was one of many reproductions of foreign locales within individual pavilions at the fair. The street added a dynamic “realism” to the exposition, allowing visitors to traverse a place that seemingly had been transposed from Egypt to the grounds of the French capital. This small section of Paris transformed into a Disneyesque magic caliphate, complete with the trappings of a stereotypical bazaar, with vendor’s stalls selling North African textiles and trinkets, accompanied by exotic music, belly dancers, and samples of food and drink that were not found on French menus at this time. The entire Gesamtkunstwerk added a sense of reality—albeit a romanticized pastiche of reality—to the experience of French men, women, and children who could interact and participate in the setting, not merely functioning as spectators.

The inspiration for the Rue du Caire was generated by the enthusiasm of the wealthy French mining engineer Baron Alphonse Delort de Gléon (1843–1899) and his passion for Egyptian art and architecture. Delort immersed himself in this area and in the culture of the Islamic world during his residence in Egypt in the 1860s and 70s, while working to transform Cairo into a city more closely aligned with Western ideas of modernization. Romanticizing the traditional elements of North African culture, Delort constructed his own elaborate homes in Cairo and Paris with liberal interpretations of Oriental exoticism, replete with formal elements of Ottoman architecture—including the genuine moucharabieh structures, projecting oriel wooden window frames, which had been salvaged by Delort from buildings destroyed in Cairo during the Haussmannization of the city.

For the French exhibition, Delort imported 50 Egyptian donkey drivers—along with their animals—from Cairo to Paris to inhabit the Rue du Caire. Visitors could take donkey rides and imagine themselves in the Cairo that they believed was authentic, but which was derived from a decidedly Western, European point of view, and part of a culture that was considered different, exotic, and primitive. The Rue du Caire was so popular at the fair that it was even depicted on a wrapper for the French chocolate manufacturer Guérin-Boutron.

The French architect and artist Joseph-René Binet was commissioned by Delort to paint 10 different views of the faux Rue du Caire in watercolor at the fair, and these works are now part of the collection of the Ecole Nationale des-Beaux-Arts in Paris, where they have not been publicly displayed until now. In City of Cinema, three of Binet’s watercolors will be exhibited at a time, in two different rotations. They depict different views of the lively and colorful street scene that greeted visitors in Paris. Each of the six watercolors illustrate different buildings, street activities, and set designs, seen from the same lower-left perspective, the streetscape receding diagonally toward the right edge of the paper. Blue skies appear in all the drawings, much more akin to the year-round weather of Cairo than the typically gray skies of the French capital. Indeed, the photographic documentation that remains from the Rue du Caire exposition installation are in black and white, so Binet’s watercolors are the only records that retain the vibrancy of what the public must have experienced under a rare blue-skied day in Paris.

Binet captured details of the various constructions made to replicate monumental gates, crenelated arched houses, a mosque, vendor stalls, street life, and tapestries, and also included a human presence. The Paris exposition mosque was a smaller-scaled copy of the Sultan Qaytbay sepulchral mosque in Cairo’s North Cemetery, and the attention to detail in replicating the building exactly was part of Delort’s pursuits to achieve an environment of artificial perfection for his audience.

Soon after it closed to visitors, the Rue du Caire was dismantled from its place in the Champ de Mars, the park in the seventh arrondissement of the Parisian Left Bank where a large part of the Exposition Universelle was installed. However, you can still visit another—permanent and real—Rue du Caire in Paris today. This street with the same name is located in the northern part of the second arrondissement on the Right Bank, and the adjacent Place du Caire (Cairo Square) contains one of the oldest covered arcades in the city. At the corner of the Rue du Caire and the Place du Caire, directly beneath the Parisian blue street sign with its distinctive white lettering, a pictorial tiled plaque displays Egyptian pyramids and camels under a crescent moon.

The exhibition City of Cinema: Paris 1890–1907 is on view through July 10, 2022.