Displayed for the first time in Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800 is a special portrait by the Mexican painter Andrés de Islas (c. 1730–c. 1783). In the second half of the 18th century, Islas had become a highly sought-after painter among the local elite, so it is not surprising that the Count of Tepa would commission a portrait by him.

Don Francisco Leandro de Viana Sáenz de Villaverde (1730–1804), was a man of high ambition who built a successful career serving the Spanish crown. Educated at the University of Salamanca, he served 10 years as crown attorney of the high court (Audiencia) of Manila in the Philippines (an important Spanish outpost). There he introduced a series of reforms designed to increase royal revenue and curtail corruption, including policing the collection of import and export taxes connected with the legendary Spanish trading vessels known as the Manila Galleons. During the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), when Britain invaded Manila in 1762, he fought tenaciously to protect Spanish interests. In 1765 he was rewarded with a more desirable appointment to New Spain’s high court.

Highly adept, Viana soon consolidated his social position by associating with Mexico’s rich clan of Basque merchants and by marrying into one of New Spain’s most prominent families. By the time Viana returned to Madrid in 1777, following his prestigious appointment to the Council of the Indies, he had amassed an enormous fortune in Mexico. Viana not only excelled as an enlightened royal bureaucrat and reformer but was also profoundly invested in projecting an image of social respectability and affluence. In 1775 he petitioned for and was granted the title of Count of Tepa by King Charles III, and in 1780 he was named a member of the Order of Charles III—a high honor bestowed on royal officials who had distinguished themselves in their service to the crown.

Based on the figure’s physiognomy and the fact that only individuals of note could afford to commission their likeness from the best artists of the day, I propose that a painting attributed to the Mexican painter Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz (1713–1772)—commonly referred to simply as Man with Clocks—is in fact the earliest known image of the Count of Tepa. He not only wears a modish reversible French-style three-piece suit ornamented with floral motifs and gold brocade, but stands next to his writing implements (attributes of his role as a judge), a clock (a traditional symbol of the precision required to rule), and a pocket watch (symbolic of his wealth and modernity). This is not a portrait of a random dandy or “petimetre” dressed in the latest fashion of the day but of a figure fully invested in his image of power and sociability.

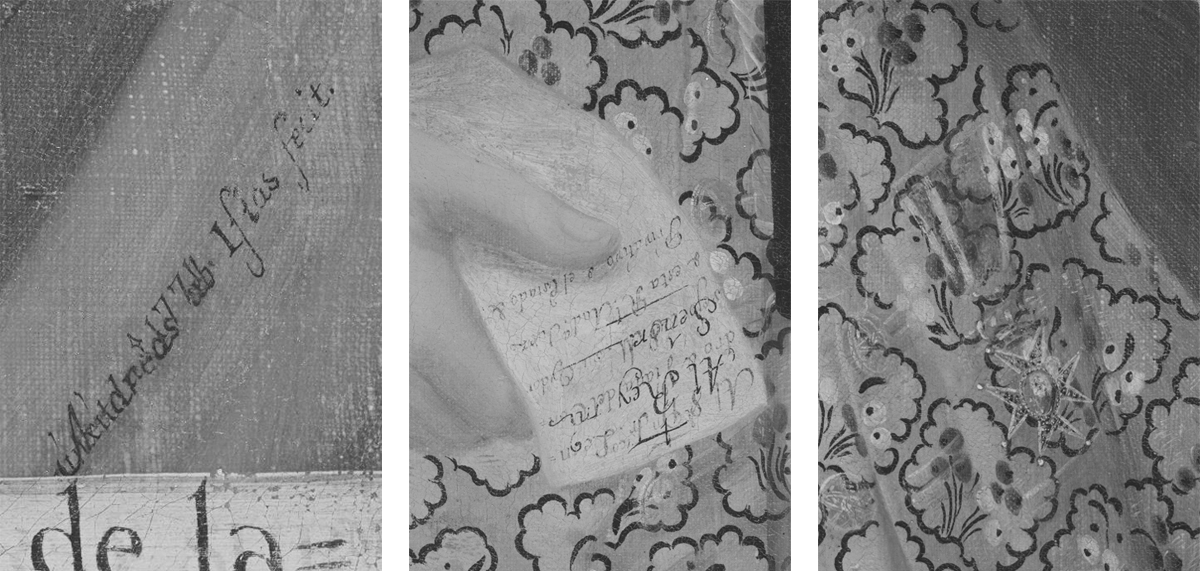

Viana may have subsequently commissioned the portrait signed by Islas to commemorate his new title as Count of Tepa. Islas portrayed him within an oval frame, traditionally reserved for important individuals, against a crimson curtain. His coat of arms is prominently displayed in the upper right. In his right hand he holds a piece of paper that reads “Al Rey mi Señor” (To my Lord the King), which alludes to his new role as a minister of the Council of the Indies and his status as an adviser to the king, while the strap of his walking stick is visible on his left wrist.

The most notable element of the portrait is the detail with which Islas depicted the count’s outfit: a fashionable French-style three-piece suit with a diaphanous lace cravat and cuffs, similar to one in LACMA’s collection. The fabric of Viana’s suit is a rendering of polychrome ciselé silk velvet called velours miniature (a complicated technique employing multiple cut and uncut warp piles on a laminated taffeta ground, here enhanced with a lamé or gold metallic threads). The design of small cartouches containing tiny bouquets was popular for men’s fabrics in the second half of the 18th century. Although tailoring was inexpensive and relatively consistent throughout the 1700s, the cloth indicated fashion and accounted for the majority of an outfit’s cost. The lavish gold of this luxury textile played a key role in demonstrating the sitter’s status. Noteworthy too is the badge of the Order of Charles III with the enameled image of the Immaculate Conception on his chest.

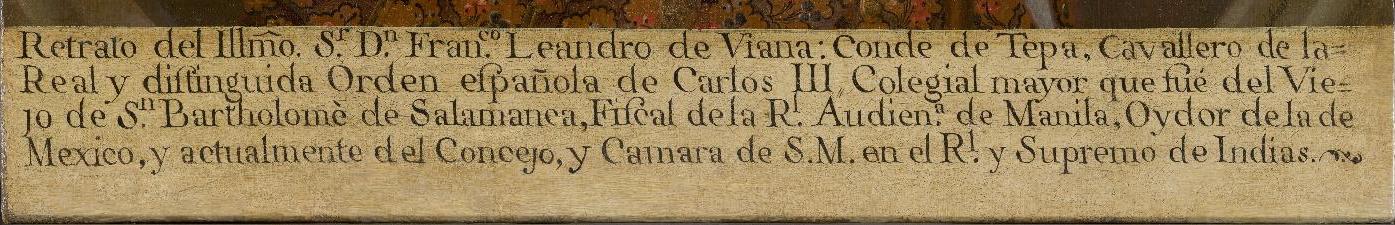

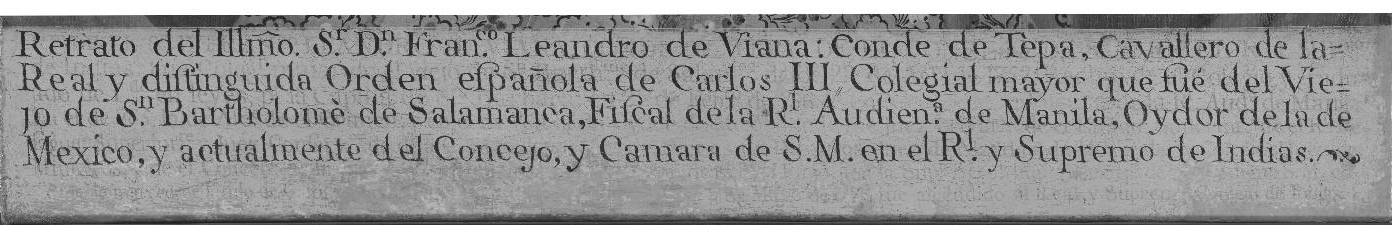

The picture’s inscription emphasizes Viana’s education at the University of Salamanca as well as his major posts in Manila and Mexico City. In addition to mentioning his new title, it also notes that Viana was a member of the Order of Charles III and that he was “currently” a member of the Council of the Indies.

Interestingly, infrared photography reveals a partial signature that reads “Pinxit anno d[e] 177[5]” (painted in the year 1775), which was altered to read “Andreas ab Islas fecit” (created by Andrés de Islas). The original signature was likely modified to better accommodate the inscription on the lower edge, which was also altered.

The earlier inscription, detectable with infrared photography, had a few additional lines—now practically illegible—and the calligraphy was smaller. Infrared photography also shows that the piece of paper the sitter holds originally bore a different message: “Al Sr Dn Fr.co Lean= / dro Viana del Con= / sejo d S. M. y oydor d esta R.l Aud.a Juez Privativo de el Estado &” (To Don Francisco Leandro Viana, from the King’s Council, and Judge of this Royal High Court, and Private Judge of the State, etc.). In other words, the letter was initially addressed to the count in his role as judge of Mexico’s high court but was changed to emphasize his direct correspondence with the king. Finally, infrared photography indicates that the badge of Charles III was added after the picture was completed.

These details suggest that the painting was likely altered after the count traveled to Madrid to assume his new post and became knighted in 1780, and that the “updated” picture was shipped to Spain at a later date to reflect Viana’s honors and promotions. This a highly revealing example of how New Spanish portraits, much like official documents, were living artifacts that could be changed, reactivated, and even silenced to suit varying circumstances and convey particular messages—in this case, to better record the illustrious background and ascending power of this important royal bureaucrat.

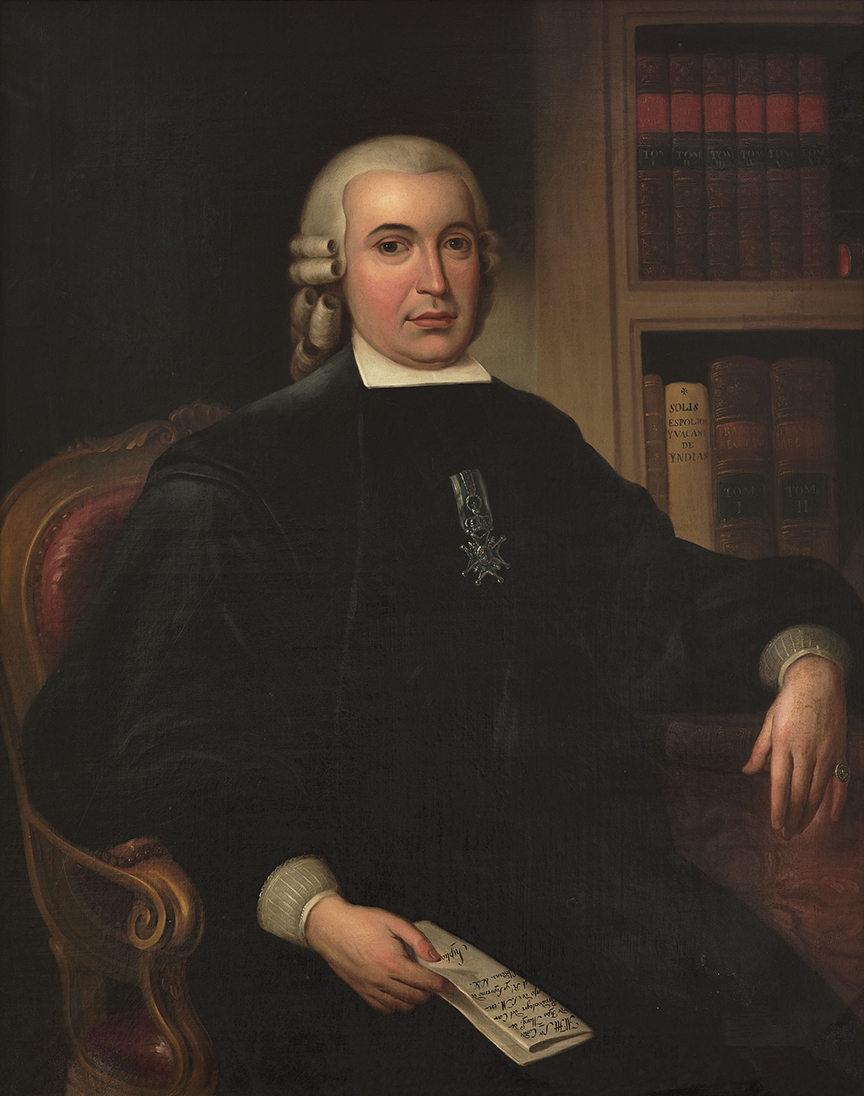

After Viana returned to the court of Madrid he openly complained of his lack of recognition by the crown after a lifetime of service, and commissioned yet another portrait, this time from the famous Valencian royal court portraitist Agustín Esteve y Marqués (1753–1820). In this later portrait the stern-looking count is depicted gazing out at the viewer, surrounded by the trappings of power and privilege: sitting in his library (to symbolize his contributions to Spanish law), wearing black attire, a simple stiffened collar, and powdered wig of a judge, and with the badge of the Order of Charles III prominently displayed on his chest. He also wears a ring, likely embossed with his coat-of-arms. The piece of paper that he holds lists his titles, including that of adviser to the King. Here, too, the painting “talked” loud and clear, giving visible form to the Count’s lofty, yet chronically unfulfilled ambitions.

Visit Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800, on view through October 30 in the Resnick Pavilion, to see this portrait with shifting messages. You can also pick up a copy of the accompanying catalogue at the LACMA Store.

Further reading:

Katzew, Ilona, ed. Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800. Exh. cat. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and New York: DelMonico Books 2022, cat. 42 (entry by Ilona Katzew).

Katzew, Ilona. “Trastoques y elipsis en un retrato de tornaviaje: La ductilidad de los mensajes.” In Tornaviaje: Tránsito artístico en los virreinatos americanos y la metrópolis, edited by Fernando Quiles, Pablo F. Amador Marrero, and Martha Fernández, 13–32. Seville: Universo Barroco Iberoamericano, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, 2020.