Many of our new acquisitions of Spanish American art made their debut in our traveling exhibition Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800. In the last year, we have continued to acquire some exceptional works that tell a fuller, more nuanced story about Spanish American art and its makers. Among these objects is this imposing, one-of-a-kind cabinet profusely decorated with mother-of-pearl and a range of intricate motifs, which was acquired during LACMA’s 36th Collectors Committee fundraiser. Because objects such as this have not been studied in any systematic way, I’m now at work consulting archives and other sources in an effort to better understand its history and potential use and meanings. I hope to share some of the new findings soon.

The cabinet was likely produced by Indigenous Guaraní artists in one of the Franciscan missions of Paraguay, possibly San Blas de Itá, which was established in 1585. Elaborately decorated writing desks with multiple drawers derive from the Spanish escritorio or papelera. The decorative scheme of this exceptional piece combines local and European motifs, reflecting the active participation of Indigenous artists in the design of Spanish-style furnishings.

Following the conquest of Peru in the 1500s, Spaniards ventured into the inhospitable Amazon basin in search of gold. The province was inhabited by different Indigenous tribes, each with their own language and traditions, whose subsistence depended on agriculture, hunting, and trade. While initially the Spaniards succeeded in forging alliances with some local groups, the situation devolved into one of open hostility as they began to exploit Indigenous peoples for personal gain.

When the Franciscans—and later the Jesuits—arrived in the area as auxiliaries of Spanish colonizers, they resorted to more peaceful tactics to attract and convert the Indigenous tribes. By the 17th and 18th centuries, they had established a complex network of largely self-sustaining missions. Their success rested in part on their recognition of the tribes’ leaders (caciques) and ancestral ways of life. To fulfill their utopic plan, they combined religious instruction with the teaching of trades, such as carpentry, masonry, weaving, and blacksmithing, among others. Mission carvers took advantage of the timber-rich area to produce a range of exquisite objects, many which were exported across the region and to Europe.

Missions became known for particular products. The Franciscan José de Parras, who visited Itá in 1753, noted that “I only found exceptional masters of carpentry and sculpture. They carve beautiful boxes and writing desks richly inlaid with nacre and shells.” Shells were abundant in the region. The Jesuit missionary José Sánchez Labrador (1714–1798) described an island known as the Isla de Conchas (Island of Shells), where Native people harvested mother-of-pearl by the bucketload and sold it in the nearby city of Asunción, remarking that the shell was employed to make “striking inlaid writing desks, tables, and cabinets.”

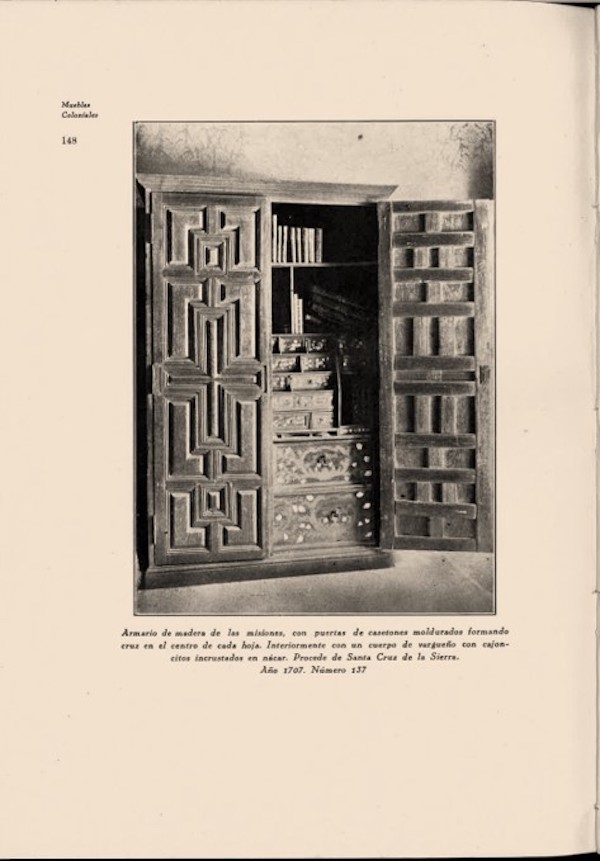

The sober exterior of this cabinet opens to reveal an exuberant writing desk inlaid with contrasting tropical woods and opalescent freshwater shells. Among the details that enliven the work are reclining figures of Indigenous chieftains, one wearing a lip ornament (a symbol of strength and virility); elements traditionally associated with the Spanish world (bulls, horses, and angels); and birds, flowers, and stylized geometric motifs.

The amphibious creatures may have had some significance in Guaraní cosmology, while the shell speech scrolls could allude to the concept of song that was essential for the Guaraní to transmit memories of their past. The shells are intricately embellished with additional motifs and pictographs that might also hold special meaning. The emphasis on symmetry and repetition is fully in keeping with the Guaraní’s more schematic and conceptual style.

The cabinet has an impeccable provenance and has been widely published since the 1930s: it was acquired in the city of Corrientes (northern Argentina) and has been documented in a prominent private collection in Buenos Aires since the early 20th century. The first work from colonial Paraguay to enter the collection, this beautiful work demonstrates the persistence of Guaraní culture within the Spanish colonial system, and the creation of dazzling new furnishing types that combined different traditions.

This piece will be on view at the Frist Art Museum, Nashville, October 20, 2023–January 28, 2024 as part of LACMA's traveling exhibition Archive of the World.