Unframed is taking a look behind the scenes to profile the dedicated, creative people who make LACMA special. We sat down with curator of photography Rebecca Morse to talk about giving artists a platform for their work, the ways in which artists revisit themes and ideas over the course of their careers, and her feelings on selfie sticks.

_0.png)

Tell us about your first experiences with art.

I started being interested in art as a young person, specifically photography. I loved poring over old images of life in New York City and how it spun my imagination. I started taking pictures. I worked in darkrooms and for photographers during summers; my background is in black-and-white film printing. I studied both art history and photography during my undergraduate years and studied with some well-known photographers—Greg Crewdson, Jan Groover, John Cohen. I did some commercial work in New York City before going on to study photo history.

What kind of commercial work were you doing?

I worked for a New York-based commercial photographer who had a specialty in tabletop photography with liquids. He had the Diet Pepsi and the Kohler accounts. He had his secrets, like how to make dew glisten on the side of a can. He had his own set of Lucite ice. Since ice melts under hot lights, photographers use plastic, but the rental ice wasn’t as detailed and specific as his personal set of ice. But I more frequently worked in the darkroom.

What did you like about being in the darkroom?

I really liked the hands-on aspect of it. It’s magical to put a piece of paper in a liquid, see an image come up, and try to get it exactly how you want it. You have a lot of control as a maker. It’s not just pushing a button. It’s about all the decisions that come before making the image in the camera, and what happens in the darkroom, with the different temperatures and light and gels and time. I think part of being a photo curator is understanding what details go into making an image.

Do many photo curators have a background in working with cameras and film?

People come to it in a variety of ways. I think that’s true of curators in general—some have MFAs, some really know it from a maker’s perspective, some come through archaeology or history. That’s what I like about the field. You can do all these other things before ending up working with artists and art materials. But I do think my background gives me a good understanding of what it means to make an image. And I really like working with artists. I’ve skewed toward contemporary art even though my early days were about looking and thinking about the past. I’m really excited to see what individuals can do with the medium, what they choose to make, and how they choose to express themselves with something that seems so mechanical.

Was there a specific moment when you realized you wanted to focus on working with artists?

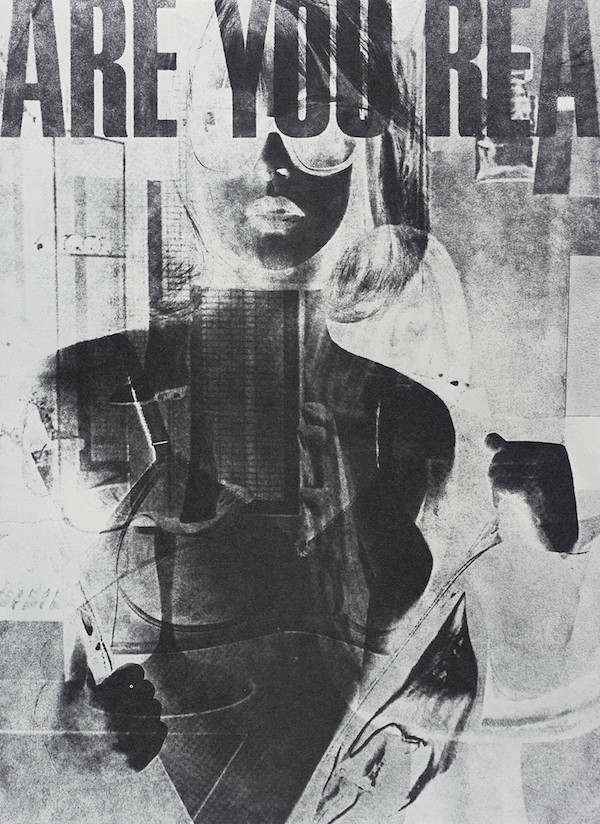

I went to graduate school at the University of Arizona in Tucson, where the Center for Creative Photography is located. My professor, Keith McElroy, had a group of us working with the artist Robert Heinecken. He was about to retire from UCLA, where he started the photography program in 1962, and he was going through all of his artwork and sending pieces to the archive at the CCP.

Previously I had been thinking about Edward Weston and pictures made in Mexico in the 1920s and 1930s. But when I started working with Heinecken, I got excited about the possibility of talking to an artist about what he is making now and what he made in the recent past. He literally went through every object in his archive with us. As a longtime professor, he was thrilled to relay all of this to students. Keith also invited Heinecken’s wife, Joyce Neimanas, and other curators and scholars to come talk to us about Heinecken, including Harold Jones, along with Heinecken himself. Those discussions gave us a picture of the artist himself, what he had made, this transition time in his own life, and how others perceived him. That was really exciting. I remember asking Heinecken very specific questions about his work, and he said to me, “It’s your job to determine what you see in my work.” That was really eye-opening. He gave me the leeway to take what I saw to another level. I’ve taken that along with me—the thought that my perspective might open something up for the artist in the way they might see their own work.

Keith always talked about how Robert Heinecken was underknown. LACMA hosted his 35-year retrospective in 2000, and he’s become better recognized over the last decade as artists of all ages and mediums have discovered his work. That’s been exciting to watch.

Then you moved to L.A.

When I moved to L.A. I lived just around the corner from here, at Fairfax and 8th. Robert Heinecken told me, “You should call up Robert Sobieszek [LACMA’s photography curator at the time] and see about getting a job at LACMA.”

So I did and was hired for a short-term job going through database records. I did that for a month or two in 1998, and then I got a job at MOCA. Fourteen years later, when I got my job here, they looked up my records and told me I was a rehire!

LACMA has a large photography collection. What would you say is the institution’s approach to photography?

LACMA has a relationship with photography that is very experimental. We have an amazing collection here, with 19,000 photographs, and we operate with the idea that photography can be all kinds of different things for all kinds of different artists.

Lately we’ve been focusing on California photography, looking at areas we haven’t collected as much, like vernacular or anonymous photography. It’s interesting to think about the difference between Northern and Southern California, because as a state, the history of photography is bifurcated. The earliest experimentation was in Northern California, based on landscape, like the work of Ansel Adams and F64 and Weston. As the years progressed, the experimentation shifted down to Southern California. The universities and art schools are so strong here and there have been major photographers and so many students. I think that makes for interesting experimentation. And now, more than ever, people who go to school here stay here. I think part of art making now is not about being part of an idea or group but about doing things as uniquely as possible.

You’ve also been actively organizing exhibitions at LACMA. Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld, which closed in early February, is the latest one you’ve worked on. It originated at the New Museum. How did it come to be here, and what was that experience like?

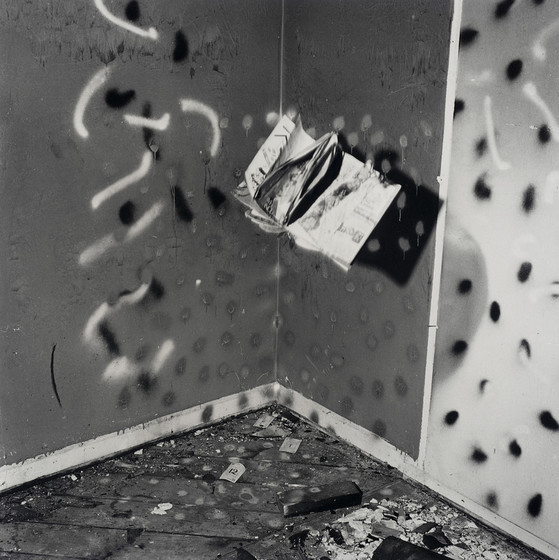

A few of my colleagues—and Barbara Kruger—saw the show in New York and suggested that it come to LACMA. We don’t always do it that way. Often, when a show is traveling, we know about it early on and we know if it’s going to come here. Anyway, we reorganized it but used the same checklist and added a few more objects. We were thinking about multiplicity and seriality, and we were able to play with the idea that one image doesn’t necessarily encapsulate everything. Charlesworth in particular would take on a problem that she would aim to solve over the course of multiple images. She would make a number of them and edit them down.

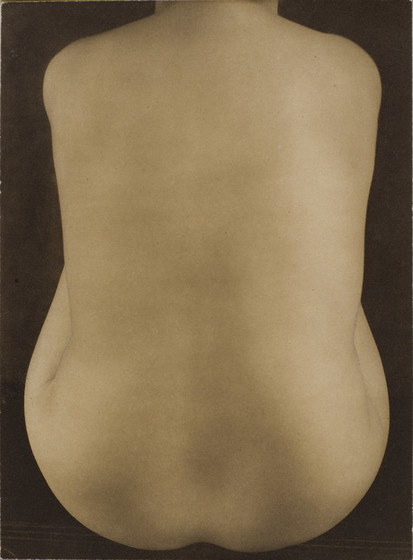

Early on she was a collagist who used found images and was particularly interested in how people were represented in the media. And then she wanted to have a greater hand in her own art production and set up situations for the camera. What she set up wasn’t so dissimilar to what she had found, but it’s a totally different approach: the first is cutting and pasting and rephotographing and the second is setting up objects on seamless paper and using a 4x5 camera. She was breaking away from early ideas and moving into another set of circumstances. We wanted to show that an artist often revisits themes and ideas over the course of their lifetime, and sometimes they don’t even know that until they are older and have an opportunity to look back on what they’ve made.

.jpg)

It was a really great show to share with the public here, artists especially. In fact, the artist Matt Lipps did a talk at LACMA; there are a few instances where the two of them had cut out the same image and used it! He could see what she was after, since he knows all these ways of preserving an image in the best possible way. They’re just photos of photos but they’re also not just that at all. It’s about all the decisions that were made. We all know that because we’re all photographers now, with everyone doing imagery searches and using their phone cameras.

What about you, do you still take pictures?

I very rarely take pictures. I have to be coerced. I don’t love my photographs. Early on, when I was dating my husband, his family asked me to take some photos of them, and I did. They were terrible! His sister has one up in her house and I laugh when I see it.

So no selfie stick for you?

No. I find myself thinking, what are you going to do with all that stuff? How are you going to organize it? Being a curator is about organizing visual information, and what goes next to what and how to keep it together, how to make meaning from these juxtapositions.

Speaking of organizing, can you tell us about the next show you’re working on?

[LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director] Michael Govan and I are co-curating a mid-career survey of Thomas Joshua Cooper for summer 2019. He’s an American living in Scotland for the last 30 years, and he makes black-and-white photographs of the ocean with a 19th-century box camera. His main project is called Atlas. He circumnavigated the Atlantic basin and gone to the outermost points of land to make a single photograph, often of the water. They’re very meditative and beautiful, and they’re about exploration, singularity, being in the moment. And climate change: these points are not going to be the outermost point for much longer as the seas rise. We’ll be doing his first museum catalogue.

Do those boards have to do with the Cooper show?

Yeah. When I first came to LACMA, I noticed a lot of people had these image boards. You could move things around, figure out where it was going to go, and see what it was going to look like. It was such a good idea, and encapsulates the feeling of congeniality and crossover among departments LACMA cultivates. I like that openness. It sparks interesting conversations early on in the creative process.

Ultimately, my goal and my interest is to give artists a platform on which their work looks the best, so that they can discover things about themselves and their art production. That’s why this work and the museum are really meaningful for people who dedicate their lives to making art. A strong museum is a strong creative environment for everybody.